An overview of declassified CIA cables on Thailand

Insights on King Bhumibol's marriage, his political interventions and distaste for democracy, and the erratic behaviour of Vajiralongkorn

In 2017, after a long struggle by freedom of information campaigners, the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States finally put 13 million pages of declassified documents online. These documents were already in the public domain, but previously could only be viewed on four computers at the U.S. National Archives in Maryland, available between 9 am and 4:30 pm from Monday to Friday. This meant that most people around the world could never see them. Now we all can. Many of the documents are heavily redacted, but they nevertheless contain many useful insights.

Nobody should assume that the CIA was right about everything — far from it — and many of the documents are heavily redacted, but they nevertheless contain many useful insights. The following is an overview of documents that help shed some light on dark episodes in Thai history. It’s in chronological order, starting with the oldest documents then moving to more recent ones.

A loveless marriage and a rumoured abdication

On June 9, 1946, the 18-year-old Bhumibol Adulyadej accidentally shot his brother King Ananda Mahidol through the head when they were playing with a Colt .45 pistol in Ananda’s bedchamber in the Grand Palace in Bangkok. The distraught Bhumibol became King Rama IX the same day, but soon fled to Switzerland, ostensibly to finish his studies at the University of Lausanne, although he actually never completed his degree. Instead he was sunk in deep depression, and terrified of having to return to Bangkok to cremate the corpse of the beloved brother he had killed.

Meanwhile, Thai royalists were split about what to do about Bhumibol. Many favoured revealing the truth about the regicide, so that Bhumibol would have to abdicate and Prince Chumbhotbongs Paribatra would become monarch instead. Others thought the best solution was to try to support the weak and troubled Bhumibol and train him to play his role as a figurehead and protector of elite royalist interests. One way they tried to do this was by arranging his marriage to the feisty Sirikit Kitiyakara, who was much more audacious and bold than the struggling young king.

According to this document from April 1950, Bhumibol had no affection for Sirikit and was trying to avoid returning to Thailand for the cremation. In the end he was persuaded to return, and ironically he was supported by the progressive faction in the Thai government, because they believed he would be easily manipulated. This was true, but the palace and military manipulated him more cleverly than the progressives, and he ended up ruling for 70 years and doing prolonged damage to Thai democracy.

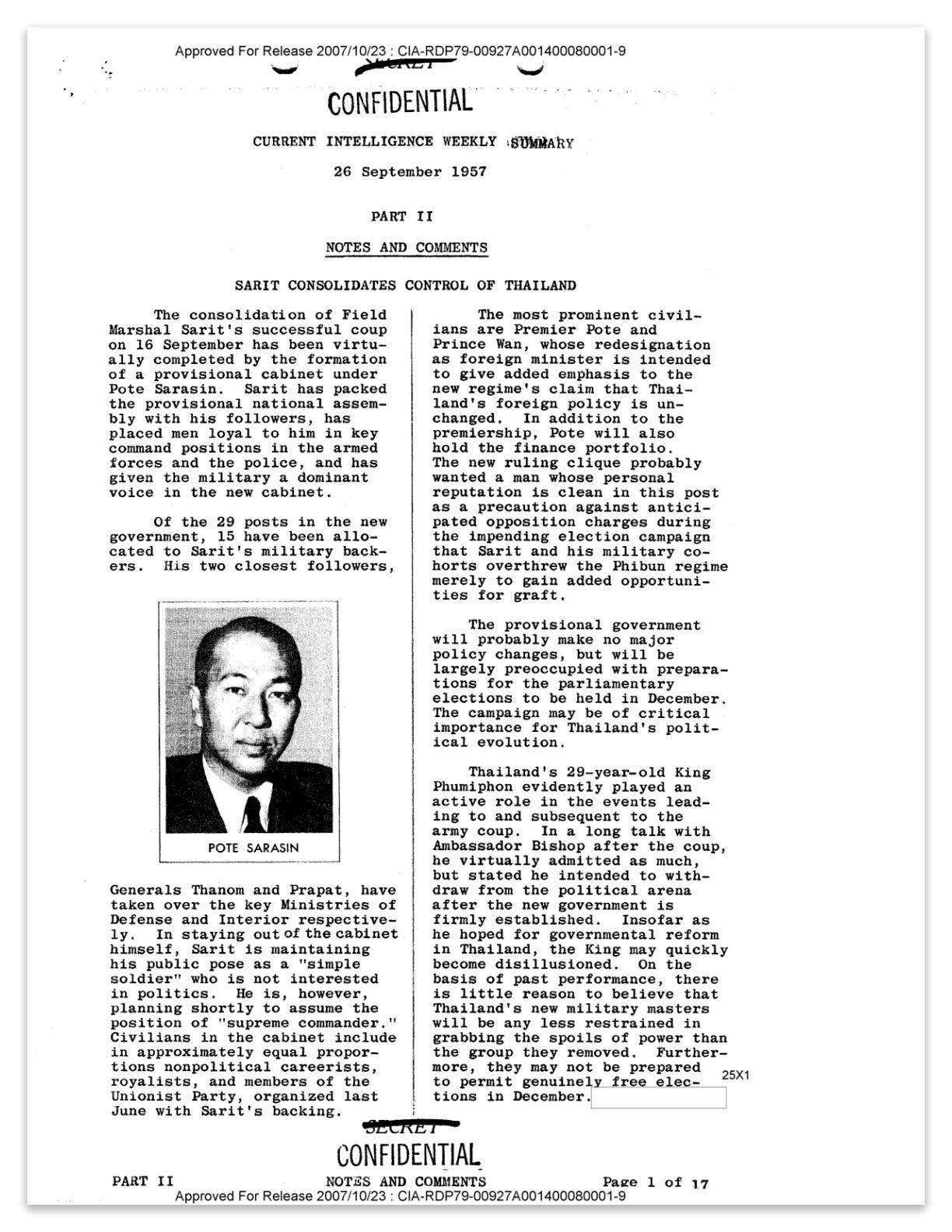

The king and his coups

In September 1957, the notoriously corrupt army chief Sarit Thanarat seized power in a coup, deposing Field Marshal Phibun Songkhram. This was the start of a remarkable palace revival in Thailand, because unlike his predecessor Sarit pretended to respect the monarchy and used royalist propaganda to bolster his dictatorial rule.

The palace has always tried to pretend that Bhumibol was above politics and never played any part in the numerous military coups that have disfigured Thailand’s modern history. But overwhelming evidence — including numerous declassified British and U.S. diplomatic cables — suggest otherwise.

This confidential CIA report from September 1957 says that Bhumibol admitted to US ambassador Max Waldo Bishop that he played an “active role in the coup”.

Bhumibol also stated that he “intended to withdraw from the political arena” after a new government was firmly established.

This proved to be entirely untrue — the coup of September 1957 was the beginning of a royalist resurgence in which the palace gradually established ever greater influence in Thai politics.

Dalai Lama not welcome

In 1959, at the beginning of a Tibetan uprising against Chinese rule, the Dalai Lama fled his country with the help of the CIA and escaped to India, where he formed a government in exile. He began pressing for the United Nations to take action on Tibet, and wanted to visit other countries to help build support for the cause.

But according to this top secret bulletin, King Bhumibol declined to welcome the Dalai Lama in Thailand, because he feared that a visit from a Buddhist leader would undermine his own claim to be the main “defender of the faith”.

A paranoid monarch

One consistent theme in diplomatic and intelligence cables about Bhumibol from several countries was his sense of paranoia. This top secret briefing to the U.S. president in June 1967 seems to share a similar assessment, warning that when the Thai king visited Washington he was likely to exaggerate the threat from communism.

Bhumibol versus democracy

In 1973, a student uprising in Bangkok led to the apparent overthrow of military dictatorship after nearly a quarter of a century. Bhumibol made a public show of support for the students at a decisive moment, and this helped foster a persistent myth — actively promoted by the palace — that he was a “democratic” king.

In fact, Bhumibol was a reactionary figure who never felt comfortable with democracy and who believed that Thailand should be ruled by the royalist elite.

Following the unexpected events of October 1973, Bhumibol quickly became disillusioned with democracy and the palace actively conspired to undermine parliamentary rule.

This led to a savage massacre of student protesters at Thammasat University by ultra-royalist forces in October 1976. Bhumibol’s complicity in the destruction of democracy in this period is well established, but this CIA document from February 1974 is interesting because it suggests that within six months of the student uprising the monarch had already given his permission to crush progressive forces in Thailand if necessary.

Worries over royal succession and political awakening

Even after the withdrawal of US troops from Thailand in the mid-1970s, America continued to consider the kingdom a key Cold War ally, but was perpetually worried that Thais might be growing more receptive to other ideas. There were also concerns about the widely despised successor to the throne, Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn.

An intelligence assessment by several US agencies in November 1981 explicitly raised worries about royal succession as a destabilising factor in Thailand, stating:

The current monarch’s great popularity and personal qualities enable him to play a key role in moderating national crises. The lack of an equally capable successor, however, suggests that the power of the monarchy and its stabilizing influence will decline with succession. Moreover, the independence of the Palace from the military is likely to decrease. and the Army‘s political power will probably grow despite the wishes of certain junior officers that the military remain aloof from politics.

The analysis also presciently forecast that increasing political engagement among ordinary Thais would become a significantly destabilising factor for the sclerotic Thai elite and their shaky status quo from the 1990s onwards.

Prem and the prince

Between 1980 and 1988 Thailand was a faux-democracy in which royalist general Prem Tinsulanonda served as prime minister on behalf of Bhumibol’s faction among the royalist elite. Meanwhile, the king’s marriage to Queen Sirikit was unravelling, and army factionalism was rife. Sirikit became close to generals who wanted to replace Prem, and also sought to pressure Bhumibol to abdicate in favour of Vajiralongkorn, who had his own favourites among the political and military elite.

In April 1984, several US intelligence agencies produced a secret joint report on Prem’s political prospects. The report mentions that Vajiralongkorn was regarded as erratic and irresponsible, and that some diplomats believed the king wanted Sirindhorn to become the next monarch instead.

The report also noted that Vajiralongkorn supported a right-wing rival of Prem. This was notorious ultranationalist politician Samak Sundaravej. Meanwhile, Sirikit had a favourite of her own — the ambitious General Arthit Kamlang-ek.

These factors destabilised the country throughout the period of “Premocracy”

The “Double 9” coup of 1985

On September 9, 1985, a group of military officers linked to a faction known as the “Young Turks” tried to seize power in an abortive uprising that was quickly suppressed. One suspected reason for the collapse of the attempted coup was that senior military officers favoured by Sirikit and Vajiralongkorn initially promised their support but panicked and backed out at the last minute.

The coup was suppressed by forces loyal to General Chavalit Yongchaiyudh. Five civilians were killed during the brief fighting, including two foreign journalists, Neil Davis and Bill Latch of NBC. The CIA analysis of the abortive coup is heavily redacted but nevertheless still useful.

One of the interesting elements of the analysis is that it explicitly discusses the splits in the royal family and their impact on events. The analysis mentions that Sirikit supported General Pichit Kullavanij, a rival to Prem and might a support a coup by him.

The uncertain kingdom

In February 1987, combined U.S. intelligence agencies produced yet another report fretting that “Thailand’s nagging political and economic problems — and expected changes in leadership — suggest that this important US ally may be headed for a period of uncertainty that could be detrimental to US interests in Southeast Asia.”

They entitled it Thailand: The Uncertain Kingdom.

In particular they were concerned that Bhumibol might soon abdicate, or that Prem would step down, and this would lead to “worrisome succession prospects”.

Nature first, protocol second

By 1986, pressure from Sirikit and her faction for Bhumibol to abdicate had become intense. The monarch shocked the nation on his 59th birthday in December that year by hinting that he would soon step aside to make way for Vajiralongkorn to rule Thailand.

“The water of the Chao Phraya must flow on, and the water that flows on will be replaced. In our lifetime, we just perform our duties. When we retire, somebody else will replace us,” Bhumibol intoned. “One cannot stick to a single task forever. One day we will grow old and die.”

This caused panic among the more liberal elements of the royalist elite, who began desperately trying to prevent Vajiralongkorn taking over. In the end it was Vajiralongkorn himself who did the most to sabotage an early succession, with a spectacular meltdown during an official visit to Japan in September 1987. Furious that his mistress Yuvathida Polpraserth had not been allowed to accompany him for reasons of protocol, Vajiralongkorn behaved petulantly throughout the trip, and eventually cut it short three days early, claiming he had been shown an unacceptable level of disrespect.

One of the incidents that apparently enraged the crown prince was that at one stage his Japanese chauffeur had to stop the car to pee en route to an official engagement.

Here is a CIA summary of the debacle. Note the handwritten comment that a U.S. official added to the document: “Nature first, protocol second.”

A gathering of spooks

The precursor of the CIA was the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, formed in 1942 under the leadership of William “Wild Bill” Donovan. The organisation had intimate links to Thailand from the start, and helped to create the “Free Thai” movement that fought the Japanese-allied government in Bangkok during World War Two.

Alexander MacDonald, founder of the Bangkok Post newspaper, was an OSS agent during the war and gifted King Ananda Mahidol the Colt .45 pistol that killed the 20-year-old monarch in 1946 while he was playing with Bhumibol in his bedroom.

Another agent was Willis Bird, who married into the family of Siddhi Savetsila (descended from British consul Henry Alabaster and the highly influential Bunnag family who were originally of Persian origin). This CIA cable from 1949 discusses efforts by the Thai military to secretly purchase weapons via Bird.

In October 1987, around 70 former OSS agents and their spouses held a reunion meeting in Bangkok. According to news reports compiled by the CIA, their most hospitable host was Siddhi Savetsila. Willis Bird, now in a wheelchair, was there too.

The assembled spies also had a special audience with King Bhumibol Adulyadej at Chitralada Palace.

Inappropriate behaviour

Bhumibol marked his 60th birthday in December 1987. Compounding the embarrassment of the crown prince’s calamitous visit to Japan, the king’s birthday was marred by several anonymous leaflets that denounced the behaviour of Vajiralongkorn and his mother Sirikit.

This episode has been covered in detail by journalist Paul Handley in his seminal biography of Bhumibol, The King Never Smiles. As Handley explains (and as the CIA apparently failed to realise) the leaflets were actually sponsored by members of the extended royal family — the relatives of Vajiralongkorn’s abandoned first wife Soamsawali.

I discuss this episode in more detail in my recent analysis of royal succession dynamics in Thailand.

That’s all for this edition. I hope you found it useful. On Friday, I’ll be publishing another original article for paying subscribers. Thanks for reading!

Yeah, the late king Bhumipol, by the 24 hours royalists propaganda for 70 years, most of thai people (including Me and my family too) was dramatically fooled, that the king, he is not only democratic but the most holiness, the most exalted living buddha who reincarnated to make merits to make good deeds for the whole country....Thank you to facebook and the Internet, now we are already “eye-opened” that what he actually do, was to maintain the power and keep control all thai people beneath under his feet all along...😿❤️🌎👍