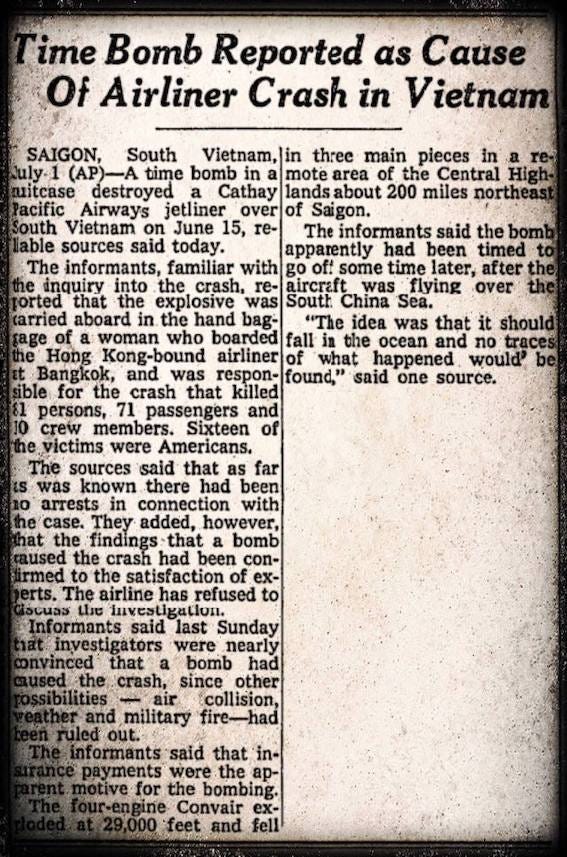

How to get away with mass murder in Thailand

The story of Cathay Pacific flight CX700Z

I. DEFINITELY NIL REPEAT NIL SURVIVORS

Just before one o’clock in the afternoon local time on Thursday, June 15, 1972, as lunch was being served to passengers at a cruising altitude of 29,000 feet over the jungled mountains of central Vietnam, Cathay Pacific flight CX700Z tumbled out of the sky.

The 11-year-old Convair 880 jet airliner, registration VR-HFZ, with 71 passengers and 10 crew aboard, began to break apart as it plunged five miles to earth, splitting into three sections — the cockpit, the central fuselage with wings attached, and the rear and tail behind the wings. The back section of the aircraft turned vertical as it fell.

Passengers who had been standing in the aisle, or queuing for the toilet, and flight attendants and pursers who were serving lunch, were sucked out of the disintegrating plane.

It took two and a half minutes to hit the ground.

The wreckage smashed onto a remote hilltop 40 km southeast of the city of Pleiku. The engines in the central section, where most of the passengers were still strapped into their seats, exploded on impact.

The rear section of the plane was impaled on a tree. Thirteen passengers and two crew were still inside. The force of the impact concertinaed the rear fuselage into a mangled stump of compressed metal and flesh just six feet long.

The cockpit crashed a short distance away and was crushed and flattened too, with unrecognisable human remains pancaked inside.

Flight CX700Z had taken off from Don Muang International Airport in Bangkok five minutes before midday. It had originally departed from Singapore earlier that morning, with a stopover in Thailand en route to the British colony of Hong Kong.

Because Vietnam was riven by war, commercial jetliners avoided flying over the north of the country, and so CX700Z had headed eastwards from Bangkok on the Green 77 flight route, which passed over Vietnam’s central highlands near Pleiku before swinging northeast over the South China Sea.

One hour, four minutes and two seconds after departure from Bangkok the plane vanished from the radar screens of Saigon air traffic control.

Shortly before dusk, a US army reconnaissance flight sighted the wreckage.

As news of the catastrophe began spreading, Cathay Pacific’s office in Hong Kong sent an urgent cable to its parent company Swire Group in London.

Managers assumed that flight CX700Z must have collided with another aircraft — perhaps a US military plane — over central Vietnam:

MUCH REGRET ADVISE CV880 REGISTRATION VR-HFZ INVOLVED MIDAIR COLLISION ABOUT 0600 RPT 0600 WEST OF QUINON SOUTH VIETNAM WHILE ENROUTE FROM BANGKOK TODAY UNDER COMMAND CAPTAIN NEIL MORISON. TOTAL 81 PASSENGERS CREW ON BOARD.But there was no confirmation that the disaster had been caused by a midair collision. Reuters initially quoted a US military spokesman as saying that the CX700Z had hit another unidentified aircraft over the central highlands, and AFP reported that the flight had crashed into a Taiwanese C-46 transport plane, but it soon became clear that no other aircraft were missing. Media began speculating instead that a lightning strike had brought down the airliner.

Because the plane had gone down in a war zone, South Vietnamese troops were drafted in to establish a secure cordon around the area and drive away encroaching Viet Cong forces with artillery strikes, while the US military airlifted a Cathay Pacific investigation team to the site, led by the airline’s operations manager Bernie Smith.

They arrived the day after the disaster. There was severe danger to the rescue and investigation teams, and one of the two South Vietnamese military helicopters sent to surveil the crash site was shot down within hours. Some of the crash debris was looted by local villagers before the site was secured.

Early media reports had suggested there could be some people still alive after the crash. But after visiting the scene, Smith telegraphed Swire Group from Saigon:

RETURNED FROM CRASH SITE DEFINITELY NIL REPEAT NIL SURVIVORSII. FIRM EVIDENCE OF AN EXPLOSION

The corpse of Dicky Kong, Second Purser on CX700Z, was lying spreadeagled a few meters from the shattered nose of the plane. His face was swollen but his uniform and body seemed intact. Nearby was the crumpled corpse of an Irish priest, Father Patrick Cunningham, dressed in his cassock and clerical collar. Around them, wreckage and dozens of bodies were strewn across the forested hilltop.

The captain of the flight was Australian pilot Neil Morison, a friend of Adrian Swire whose family conglomerate owned the airline. The plane was being piloted by First Officer Lachlan Mackenzie, and also in the cockpit were First Officer Leslie Boyer and Flight Engineer Ken Hickey. There were six Hong Kong cabin crew — two pursers, William Yuen and Dicky Kong, and four flight attendants, Winnie Chan, Ellen Cheng, Tammy Li and Florence Ng.

Morison’s corpse was eventually recovered from the crushed cockpit, identifiable only because his remains were still partially held together by his uniform. The bodies of Boyer and Hickey were identified in the Saigon morgue where the dead were taken. No trace of Lachlan Mackenzie was ever found.

Most of the passengers were Japanese, Thai and American, including several families. Seven members of one US family surnamed Kenny were aboard, as were eight members of a Filipino family on their way to Manila— civil servant Norberto Fernandez, his wife, their five children, and his niece.

As the team sent by Cathay Pacific recovered evidence from the scene, two British air accident experts, Vernon Clancy and Eric Newton, were flown to Vietnam to examine the remnants of the plane.

Painstakingly, they reconstructed the final minutes of flight CX700Z.

Examining the central fuselage of the stricken aircraft, they found overwhelming evidence that a blast had punched a hole in the plane beside seat 10F, over the wing. At least one passenger, and one or two seats, were sucked out of the gap and smashed into the tail, breaking off the rear right-hand stabiliser.

The explosion also punctured and ignited the plane’s right-hand fuel tank, setting part of the fuselage ablaze. With one of its rear stabilisers destroyed, the aircraft pitched upwards, yawed to the right, and turned upside down.

The blast severed the mechanisms beneath the cabin floor that enabled the pilots to control the plane. They were helpless to stop the unfolding disaster.

The fact that the corpses of cabin crew were still dressed in their clothing for serving food, and that several passengers had been apparently standing in the aisle when the plane disintegrated, suggested the disaster had happened without warning.

There was no evidence of panic or foreknowledge that a catastrophe was unfolding. They had been cruising safely over Vietnam, with no indication anything was wrong, and then suddenly they were hurtling downwards in a crippled aircraft that was breaking apart.

In his confidential report to the Vietnamese Director of Civil Aviation in Saigon, veteran British investigator Vernon Clancy wrote:

There is firm evidence of an explosion of a substantial quantity of high explosive within the aircraft, probably within the cabin in way of the wing roots.Cathay Pacific CX700Z had not been destroyed by a mid-air collision. It had not been hit by a bolt of lightning. It had been blown out of the sky by a bomb.

III. FOR YOUR INFORMATION THERE IS ONE MAJOR SUSPECT

Investigators established that the bomb that brought down CX700Z had exploded between rows nine and ten on the right side of the plane — which meant it must have been stowed in front of seat 10E or 10F.

These seats had been occupied by two Thais — a seven-year-old girl called Sonthaya Chaiyasut, and a 20-year-old woman called Somwang Prompin, a hostess who worked at an all-night bar, the 24-Hour Café in Siam Square. The two had been travelling together, and had boarded the plane in Bangkok.

Sonthaya was the daughter of Lieutenant Somchai Chaiyasut of the Thai Police Aviation Division and his Filipina ex-wife Alice Villiagus. Somwang was the 29-year-old Somchai’s latest girlfriend.

Somchai, who was based at Don Muang, had behaved strangely on the day of the crash. He had accompanied his girlfriend and daughter to the Cathay Pacific check-in counter at the airport, wearing his full police uniform, and demanded that they were given seats 10E and 10F, over the plane’s right wing. When told that these seats had already been allocated to other passengers, and that Sonthaya and Somwang had been given seats 15E and 15F, he tried to insist their seats be changed.

Eventually he convinced the Cathay Pacific superintendent at Don Muang to board the plane and persuade a Japanese passenger to switch seats so that Sonthaya and Somwang could have 10E and 10F. Somchai claimed his girlfriend and daughter wanted the seats to have a good view — even though the view from 15E and 15F was much better because it wasn’t obscured by the wing.

Sonthaya and Somwang did not check in any luggage for the flight. Somwang carried just one piece of hand luggage — a cosmetics case — which she took onto the plane and stowed under the seat in front of her.

In the frantic, traumatic aftermath of the crash, Cathay Pacific flew bereaved relatives to Saigon to help identify the bodies that had been recovered. Lieutenant Somchai was among them.

Cathay Pacific officials were unsettled by his behaviour in Saigon — he showed little interest in finding their remains, but was insistent that he wanted Somwang’s cosmetics case returned to him. Instead of showing grief over the deaths of his girlfriend and daughter, he badgered officials with the same insistent question — did they know what had caused the crash? His behaviour was strikingly different from the other bereaved relatives. It was widely noticed by the Cathay officials who dealt with him in Saigon.

In any case, the body of his daughter, seven-year-old Sonthaya Chaiyasut, was never found. Investigators concluded that she had been in the window seat, 10F, and had been sucked out of the plane along with her seat when the bomb detonated. It was her body, and the seat she was strapped into, that smashed into the jetliner’s rear stabiliser and caused the plane’s catastrophic loss of control.

Somwang’s body was recovered, however, and was identified thanks to the work of Wesley Neep, a former chief of the US Army Mortuary in Saigon. Her legs had been blown off below the knee and her face and hands were also missing — suggesting the bomb may have been in the cosmetics box she had stowed under the seat in front of her, and perhaps detonated as she was bending forward to open it.

Cathay Pacific officials soon learned further disturbing information. Somchai had bought travel accident coverage for Somwang and Sonthaya from American International Insurance and New Zealand Insurance. In the event of their deaths, he stood to get 3.1 million baht — worth around $225,000 at the time.

“For your information there is one major suspect who is a lieutenant in the Thai police and who is at present in Saigon with some of the other next-of-kin,” wrote Cathay Pacific chairman Duncan Bluck in a letter to Swire Group in London. “He is alleged to have insured his common law wife and daughter for a large sum. It is known that they had no hold baggage, and only one suitcase which was placed under the seat specifically requested by him for his common law wife.”

IV. ONE OF THE WORST MASS MURDERERS IN HISTORY

Little progress was being made in the official Thai investigation, and news reports suggested the regime was deliberately dragging its feet.

So Cathay Pacific ordered their chief security officer, former colonial policeman Geoffrey Binstead, to investigate further in Bangkok. Thai police were generally unhelpful but Binstead began informally sharing information with Colonel Term Snidvongs of the Crime Supression Division, a Thai aristocrat who was also a keen aviator, and who also wanted to discover what had happened.

In Siam Square, Binstead spoke to two of Somwang’s friends, nicknamed Tommy and Dang, at the 24-Hour Café.

“They are hostesses whose company can be hired,” he wrote in an investigation report. The women told him that Somchai had frequently visited the 24-Hour Café, and that Somwang had moved in with him about six weeks before the crash.

Somchai had quickly proposed marriage, and asked her to fly to Hong Kong with his daughter Sonthaya. He said they would be met by his mother, who would give her $500 for shopping, and he would join them in a few days.

Binstead also learned that it was not the first time that Somchai had tried to persuade a Thai woman to take his daughter on an international flight. He tracked down a hostess called Sathinee Somphitak who worked at the Café de Paris, a restaurant and bar in Patpong. She told him Somchai had offered her 30,000 baht to accompany Sonthaya on a shopping trip to Hong Kong.

She initially agreed, but became suspicious and asked him for an advance of 5,000 to test his sincerity. When he refused, she backed out of the plan. It was a decision that saved her life.

On August 31, 1972, Lieutenant Somchai Chaiyasut was arrested at the police aviation centre at Don Muang, stripped of his rank, and charged with premeditated mass murder and sabotage.

He insisted he was innocent, despite the overwhelming evidence against him.

Somchai’s trial began on May 11, 1973. At his first appearance before the panel of three Criminal Court judges who would decide his fate, he pleaded not guilty.

“The neatly-dressed defendant, who stands accused of a crime which could make him one of the worst mass murderers in history, looked nervous and ill-tempered,” reported the Bangkok Post. “But he appeared to get a grip on himself after getting his shoulder patted by defence counsel.”

The defence counsel was his father Sont, a well-known Bangkok lawyer. Somchai Chaiyasut had a well-connected family, and his defence was to receive some very influential support.

V. ONE BULLET MAY NOT BE ENOUGH

Thailand at the time was ruled by a hated triumvirate of military dictators — field marshals Thanom Kittikachorn and Prapas Charusathien, as well as Thanom’s son Colonel Narong who was married to a daughter of Prapas.

“We have collected enough evidence to prosecute the case and the punishment will undoubtedly be execution before a firing squad,” declared Narong after Somchai was arrested. “One bullet may not be enough. It should be 81.”

But the junta soon became uneasy about the case and the international attention it was attracting. Obsessed with Thailand’s image abroad, they fretted that the kingdom would look bad in the eyes of the world if a Thai policeman was convicted of such a grievous crime.

The fact the bomb had been smuggled aboard the plane at Don Muang was also an embarrassment to the dictators, who had long boasted about the airport’s excellent security.

Prapas began insisting that Somchai must be innocent, because it was inconceivable that a Thai man would murder his own child. He claimed that Cathay Pacific had concocted the allegations to discredit Don Muang and bring greater air traffic to Hong Kong’s rival Kai Tak International Airport.

Asked about these absurd claims, a Thai government spokesman told reporters: “Field Marshal Prapas and other officials have said there was no bomb on the plane, this was only the propaganda of another airport to destroy the good name of Don Muang.”

The evidence presented at the trial appeared damning.

An official at the Thai embassy in Saigon testified that Somchai had been insistent on the cosmetics case being returned to him. Four similar cases were found in Somchai’s house, and he had drilled holes in two of them. His explanation was that he had planned to put a walkie talkie or camera in the cases and this was the reason for the holes.

A Thai police pilot told the court that he gave Somchai two pounds of C4 plastic explosive during a training course they had both attended. Another police witness said Somchai had asked him where would be the most effective place to plant a bomb on an aircraft, and he had replied it would be near the wings. An airline engineer said Somchai had quizzed him about the effects of a blast in a jetliner. Sathinee Somphitak told the court about Somchai’s effort to persuade her to take his daughter to Hong Kong.

There were 67 witnesses for the prosecution, and only four for the defence.

Somchai continued to protest his innocence. At one point he wailed: “How could I kill my own daughter?”

On May 30, 1974, the head judge, Criminal Court deputy director Chitti Vuthipranee, delivered his verdict.

In a two-and-a-half-hour summing up, he said the court accepted that a bomb had brought down flight CX700Z, but there was no proof Somchai had planted it. No witnesses had seen him placing explosives in the cosmetic case, and Somwang had not noticed anything amiss. Surely she would have noticed the extra weight if a bomb was inside?

The judge declared that the testimony of the police officer who said he had given C4 explosive to Somchai was not credible, asking: “Why didn’t he use it himself? Why did he deliberately give it to Somchai?”

Moreover, the judge declared, Somchai’s family was not poor, and there was no reason for him to kill his own flesh and blood just for the sake of money.

The verdict: not guilty.

“Hundreds of spectators standing on tables, chairs and benches and in a solid mass across the floor of the stifling, airless court greeted the verdict with cheers, deafening applause and a blaze of flashbulbs,” wrote New Zealand journalist John McBeth in his report for the Bangkok Post.

Recalling the case four decades later in his memoir Reporter, published in 2011, he wrote: “As with many people involved with the case, I was appalled that — blinded by nationalistic sentiment and the notion that one of their own could not possibly have committed such a crime — many Thais seemed oblivious to the injustice of it all.”

The prosecutor launched an appeal, and another trial was held. The verdict, when it came in 1976, remained the same — not guilty.

Somchai Chaiyasut returned to his job at the Royal Thai Police. He took the insurance companies to court to force payment of the travel accident policies he had taken out for Somwang and Sonthaya, and by 1978 he had received his 5.5 million baht. In 1983 he moved to the United States.

Distraught relatives of the dead were aghast at the verdict, which made a mockery of the Thai justice system. Some even considered hiring a hitman to kill Somchai.

But in the end, there was no need. In 1985, Somchai returned to Bangkok after being diagnosed with liver cancer, and died shortly afterwards. He was 43 years old.

Beyond words. 81 to 1. How those judges doing?