"I could kill you, too"

The truth about the death of King Ananda Mahidol

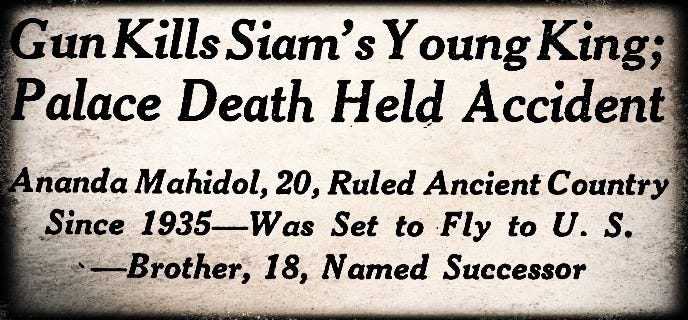

On the morning of June 9, 1946, the 20-year-old Ananda Mahidol, King Rama VIII of Siam, was shot through the head and killed in his bedroom in the Barompiman Hall building in the Grand Palace complex in Bangkok. Later that day his 18-year-old brother Bhumibol Adulyadej was proclaimed King Rama IX.

Officially, the killing is described as a mystery, one of the world’s most extraordinary unsolved crimes of the past century. In reality, it has long been clear who killed Ananda.

The truth has been suppressed by Thailand’s establishment, partly through use of the draconian law of lèse majesté, Article 112 of Thailand’s criminal code, which has been used to criminalize open and honest discussion of Thai history and politics.

Within minutes of Ananda’s death, the crime scene was deliberately tampered with to hide the evidence of what really happened. Those who were in the Barompiman Hall that morning never publicly revealed the truth of what happened, and all are now dead.

The official investigation into Ananda’s death considered three possibilities — that he was murdered, committed suicide, or shot himself by accident.

The investigation deliberately excluded a fourth possibility — that Ananda was accidentally shot by somebody else. This fourth possibility is what actually happened. Ananda Mahidol was shot and killed by his brother Bhumibol.

It seems inconceivable that the killing was premeditated. It was a terrible tragic accident or aberration, and it haunted Bhumibol for the rest of his life.

Despite the destruction of evidence, and the fact that those involved lied about what happened, it is possible to reconstruct how Ananda died.

The first key point is that there is no credible possibility that an unknown assassin sneaked into the Grand Palace that morning, took Ananda’s Colt .45 automatic pistol from his bedside cabinet, shot him through the head with it, and escaped, unseen by anyone. The killer can only have been somebody in the Barompiman Hall.

In the immediate aftermath of Ananda’s death, it was widely assumed that he had commited suicide. The large assembly of princes and politicians who gathered downstairs in the Barompiman Hall after Ananda’s death did not spend much time debating whether he had been assassinated by an intruder — as they surely would have done if there were genuine suspicions that this had been the case — but instead fretted over how to explain Ananda’s death to the public. Ananda’s mother Sangwan begged Pridi Banomyong, the statesman who was prime minister at the time, to declare that the shooting was a self-inflicted accident rather than suicide. Partly in order to preserve royal prestige, Pridi and the government complied.

But the story that Ananda shot himself by mistake was never remotely plausible. The Colt is a relatively heavy handgun, weighing more than a kilogram when fully loaded, and to be fired it requires considerable pressure to be placed not just on the trigger but also simultaneously on a safety panel on the back of the butt. The chances of Ananda doing this by accident, while the gun was pointed at his forehead, were extremely slim. Furthermore, the gun was found lying beside Ananda’s left hand. But he was right handed. Also the evidence seemed to suggest that Ananda had been lying flat on his back when he was shot. And he had not been wearing his spectacles, without which his vision was appalling. It seemed barely credible that Ananda would have been playing with his Colt .45 while lying on his back and without his glasses.

Suicide was a slightly more credible theory, but for many of the same reasons that ruled out Ananda accidentally shooting himself, it seemed desperately unlikely. It is almost unheard of for somebody to commit suicide lying on their back, and the trajectory the bullet had taken through Ananda’s skull was also very unusual for a suicide.

Within hours of Ananda’s death, royalist politicans — in particular Seni Pramoj — began spreading rumours that Pridi Banomyong had conspired to have Ananda murdered. This allegation was entirely bogus, and no credible evidence has ever been produced to support it. But Ananda’s death was exploited by the royalists to smear Pridi, with disastrous consequences for Thailand.

On June 13, US chargé d’affaires Charles W. Yost sent a secret cable to the Secretary of State in Washington, entitled: “Death of King of Siam”. Yost predicted:

The death of Ananda Mahidol may well be recorded as one of the unresolved mysteries of history.

Yost recounted a conversation with Pridi, who was shocked by the rumours and false accusations implicating him in regicide:

The Prime Minister spoke to me very frankly about the whole situation and ascribed the King’s death to an accident, but it was obvious that the possibility of suicide was in the back of his mind. He was violently angry at the accusations of foul play levelled against himself and most bitter at the manner in which he alleged that the Royal Family and the Opposition, particularly Seni Pramoj and Phra Sudhiat, had prejudiced the King and especially the Princess Mother against him. He repeated several times that he had been overwhelmingly busy attempting to rehabilitate and govern the country and had not had time to have luncheon and tea with Their Majesties every day or two as had members of the Opposition… Pridi said that the King had always behaved most correctly as a constitutional monarch and that their relations had, in spite of the prejudice planted in the King’s mind, been friendly and correct. He admitted frankly however that his relations with the Princess Mother were hopelessly bad and he feared greatly that his relations with the new King would be poisoned in the same manner as had his relations with King Ananda.

Yost wrote in conclusion that Pridi “still intended to endeavor to work with the new King and his mother”.

The following day, another cable from Yost, “Footnotes on the King’s Death”, discussed the various theories about Ananda’s death, and recounted a conversation with Foreign Minister Direk Jayanama who had just had an audience with Bhumibol. It was also classified secret:

The Foreign Minister…informed me that he an audience this morning with the new King in which His Majesty had inquired about rumours in regard to his brother’s death are still being spread about. According to Direk, he replied that the rumours are still being circulated widely, that some claim that the King was murdered by the orders of the Prime Minister, some … murdered by former aide-de-camp and some that he committed suicide under political pressure. King Phumipol thereupon informed the Foreign Minister that he considered these rumours absurd, that he knew his brother well and that he was certain that his death had been accidental… What the King said to Direk does not necessarily represent what he really believes, it is nevertheless interesting that he made so categorical a statement to the Foreign Minister.

Yost also reported that Seni Pramoj was explicitly attempting to smear Pridi by sending emissaries to the US and British embassies claiming that the prime minister had plotted to kill Ananda:

The Department may also be interested to know that within 48 hours after the death of late King two relatives of Seni, first his nephew and later his wife, came to the Legation and stated categorically their conviction that the King had been assassinated at the instigation of the Prime Minister. It was of course clear that they had been sent by Seni. I felt it necessary to state to both of them in the strongest terms, in order to make it perfectly clear that this Legation could not be drawn into Siamese intrigues, that I did not believe these stories and that I considered the circulation at this time of fantastic rumours unsupported by a shred of evidence to be wholly inexcusable.

The cable noted that the British Ambassador, Sir Geoffrey Thompson, told Yost he had been visited by several politicians telling a similar story. Thompson had told them he accepted the official account of Ananda’s death and refused to discuss the matter further.

Faced with this rumourmongering, Pridi’s position became increasingly difficult. On June 18, his government set up a commission of inquiry tasked with finding out the truth about Ananda’s death. It was chaired by the chief judge of the supreme court, and included three senior princes; the heads of the army, navy and air force; the chief judges of the criminal and appeals courts; and the speakers of the upper and lower houses of parliament.

The commission appointed a medical sub-committee of 20 doctors: 16 Thai, two British, one American and one Indian. The doctors did some genuine — if belated — forensic work on Rama VIII’s body. On June 21 Ananda’s corpse was removed from the funeral urn, and the head was X-rayed.

But as noted earlier, the parameters of the panel’s work were deliberately skewed. The doctors were told to choose from three possibilities: was Ananda murdered, did he commit suicide, or did he accidentally shoot himself? The fourth possibility, that Ananda was shot accidentally by somebody else, was never mentioned.

As the doctors were carrying out their investigations, royalists spread rumours that Bhumibol’s life was in danger too. And in their most audacious attempted power grab of all, they tried to use their scaremongering to win support from the British ambassador for a palace-sponsored coup against Pridi Banomyong and his government. Yost informed Washington of this in a June 26 cable classified top secret:

A member of the Royal family a few days ago sought from the British Minister support for a coup d’état, claiming otherwise the Dynasty would be wiped out. Thompson categorically refused to support and warned the petitioner of probable fatal consequences of any attempt of this kind.

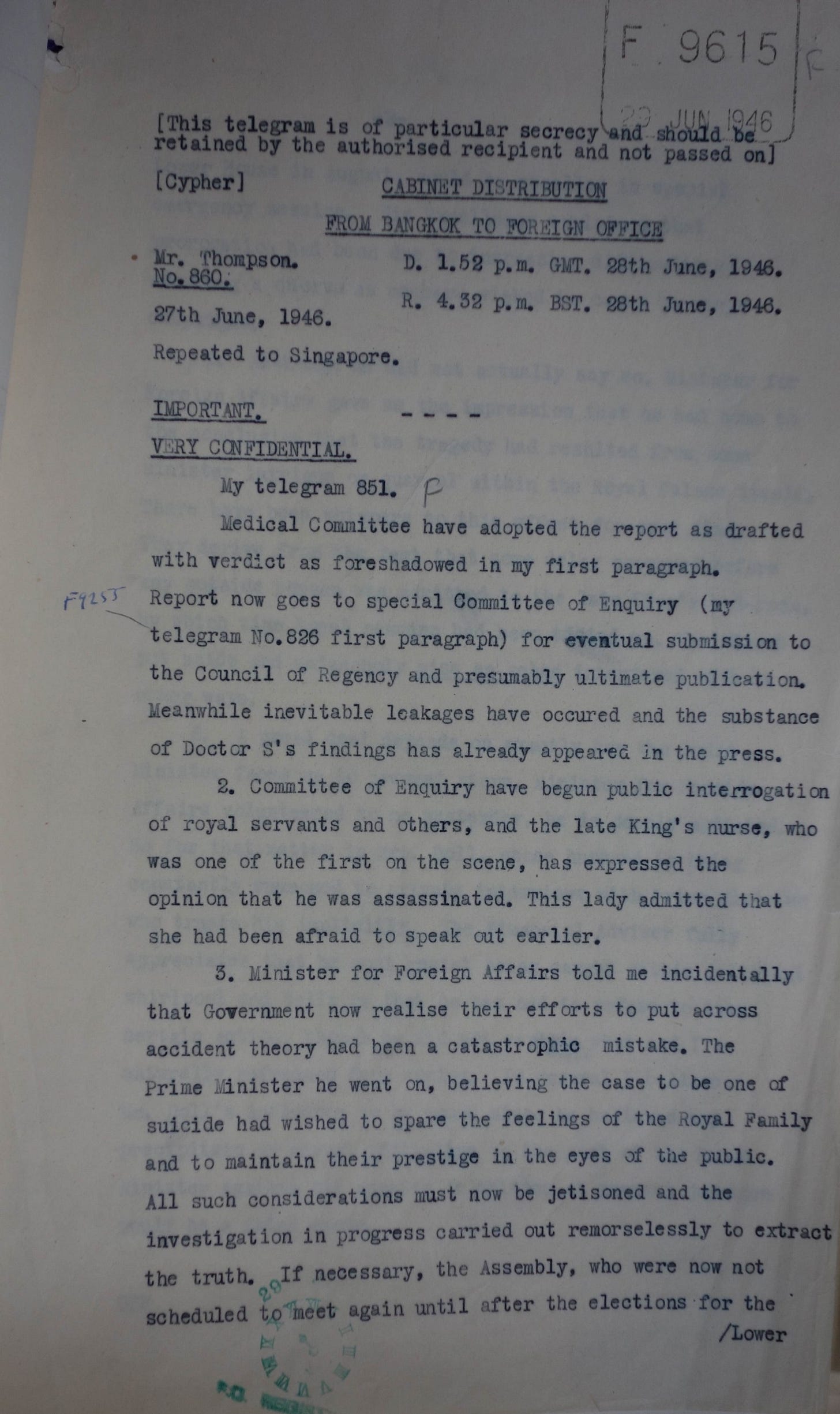

The report of the medical panel was completed on June 27 and can be viewed in full here. Most of the doctors ruled out a self-inflicted accident and also considered suicide highly unlikely. They believed the evidence showed that somebody had shot King Ananda.

Also on June 27, a secret cable from British ambassador Geoffrey Thompson noted remarks from Direk suggesting there had been a deliberate cover-up in the palace after Ananda was killed. See paragraph 4:

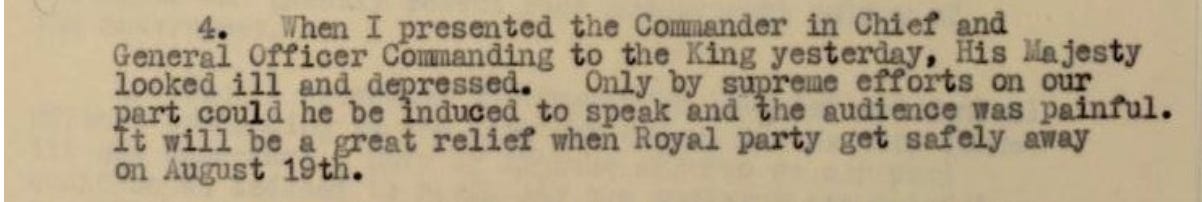

Bhumibol was clearly desolated by his brother’s death. He and Sangwan also made plans to return to Lausanne, even though the 100-day mourning period was not complete. A secret cable from Geoffrey Thompson on August 17 reports that he looked sick and could hardly speak.

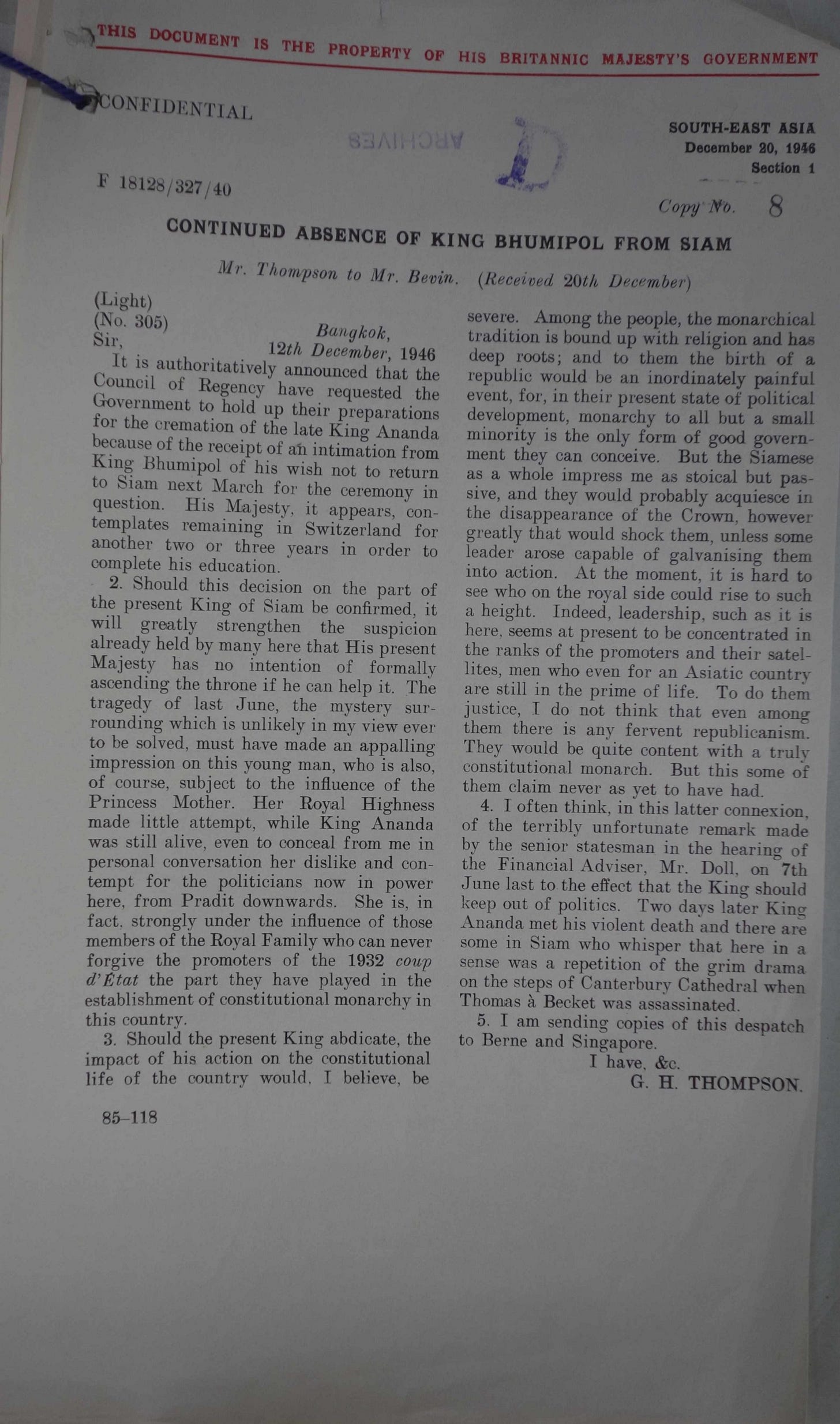

On August 19, a date set by royal astrologers, Sangwan and Bhumibol set off for Lausanne in a plane provided by the British. Officially, Thailand’s new king was returning to Switzerland to complete his studies at the University of Lausanne. But he remained profoundly depressed, rarely attended classes, and never completed his degree. In late 1946 he sent word that he would not be returning to Bangkok any time soon for the traumatic cremation ceremony for Ananda. As a British cable reported in December 1946, there were widespread rumours that he would abdicate the throne.

Meanwhile, investigations into Ananda’s death were increasingly pointing to the overwhelming likelihood that Bhumibol was responsible. The government, fearing the destabilizing impact of such a revelation and unwilling to provoke Bhumibol’s abdication and replacement by Prince Chumbhot, suppressed the information about Bhumibol’s involvement and imposed censorship.

On November 8, 1947, Thailand’s royalists allied with the militarist clique of Phibul Songkram overthrew the government. They used the widespread popular belief that Pridi was hiding crucial evidence about Ananda’s death to legitimize their power grab. Pridi Banomyong fled Thailand in fear of his life.

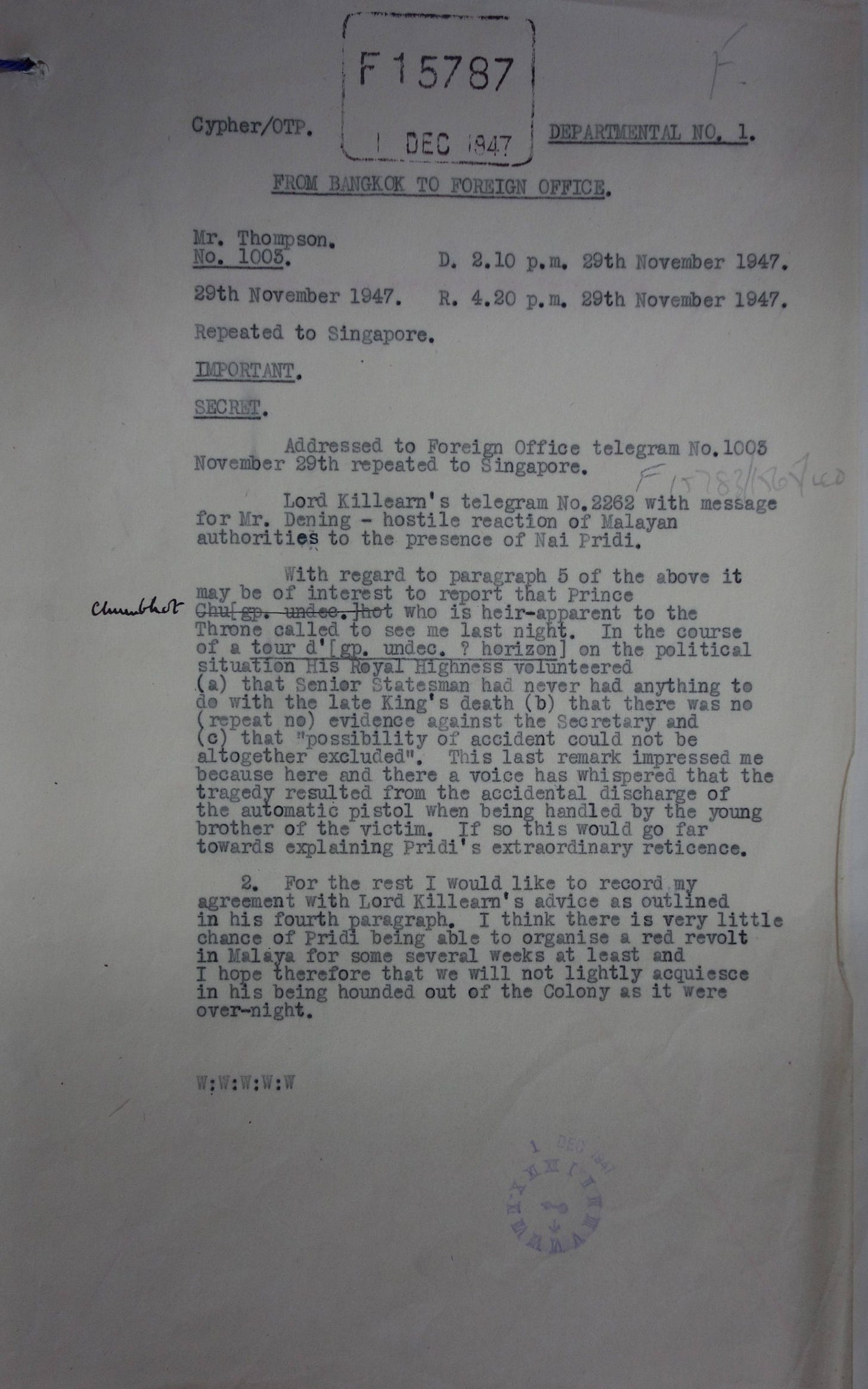

In the days that followed, royal pages But Patamasarin and Chit Singhaseni were arrested, along with former royal secretary Chaliew Pathumros. The new government alleged they had been part of a communist plot masterminded by Pridi to murder Ananda. This story was totally untrue, as Prince Chumbhot, heir apparent to the throne, acknowledged to British ambassador Geoffrey Thompson on November 28, 1947. The ambassador shared Chumbhot’s remarks in a secret cable the following day.

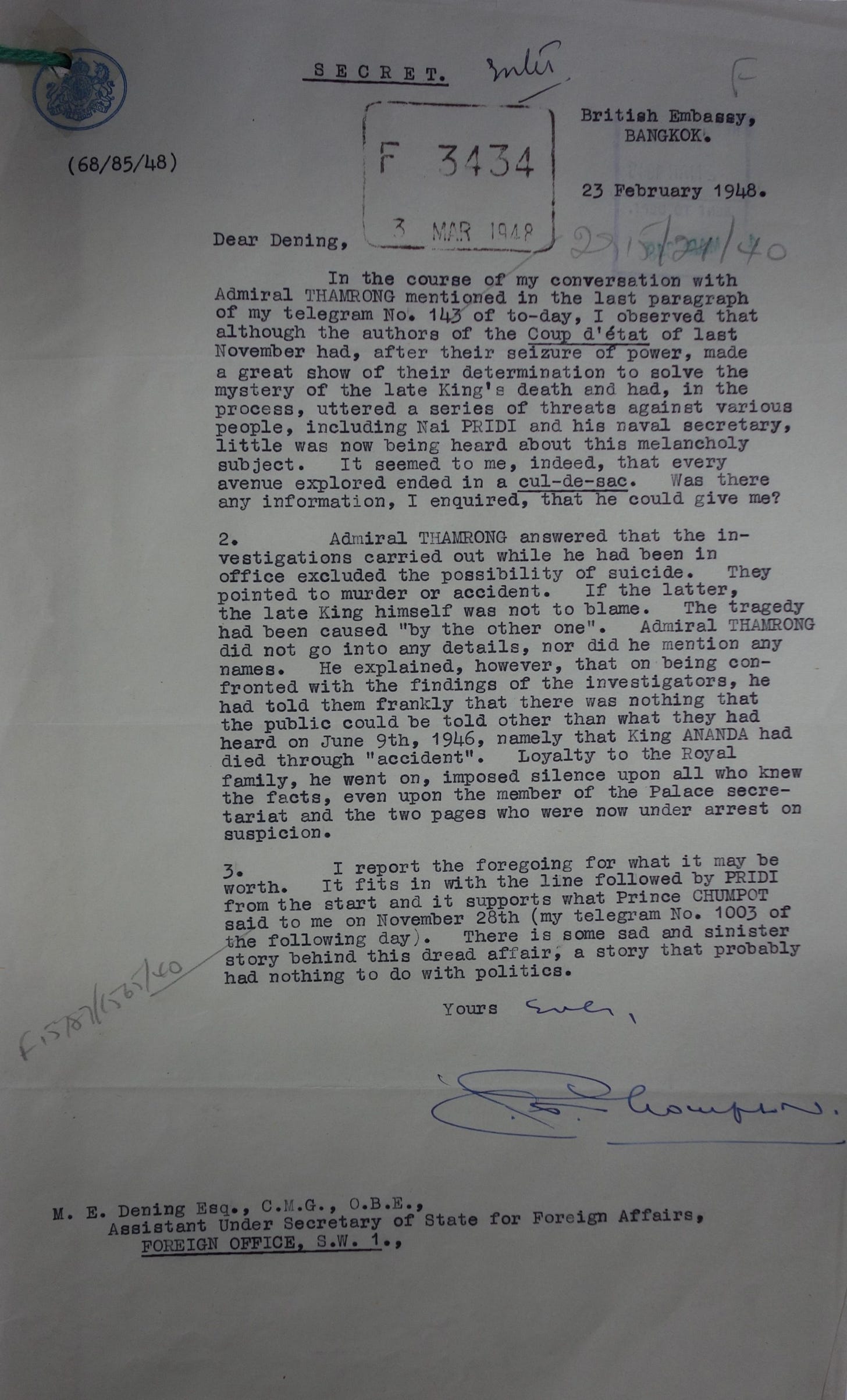

In February 1948, Thompson discussed the death of Ananda with Admiral Thamrong Navaswadhi, who had been prime minister from from August 1946 until he was deposed in the November 1947 coup. Thamrong dropped heavy hints that Ananda had been shot by Bhumibol and that the government had felt unable to announce this.

A month later, Thamrong was even more explicit in a conversation with US ambassador Edwin Stanton over tea on March 30, 1948.

Meanwhile, increasingly alarmed about Bhumibol’s refusal to return from Lausanne, and concerned that his complicity in Ananda’s death would disastrously weaken him as a monarch, leading royalists including Democrat Party leader Khuang Aphaiwong, and the Pramoj brothers Seni and Kukrit, hatched a plan to announce that Bhumibol had killed Ananda. They hoped to force him to abdicate in favour of Prince Chumbhot. This inconvenient piece of history is something the modern-day Democrat Party refuses to admit. The news was cabled to Washington by State Department Southeast Asia Division assistant chief Kenneth Landon on February 20, 1948:

The most recent reports in connection with the assassination of King Ananda to the effect that Khuang is preparing to announce that King Bhumiphol killed his brother accidentally; that Bhumiphol will abdicate and that Prince Chumphot will become King inject new elements into the situation which may profoundly disturb present political arrangements…

Phibun is antagonized by Khuang’s proposal that … Chumphot become King. It may be true that Bhumiphol killed his brother either intentionally or accidentally. Such a possibility was indicated by an earlier memorandum by me on this subject… This then becomes a deliberate attempt by Khuang to restore the monarchy to some of its former power and to establish Khuang and the Pramoj brothers firmly as the leaders of a royalist party and of the nation. They apparently hope that they can sustain themselves with Chumphot on the throne because Chumphot is a mature person of considerable wealth who has had long experience with palace politics, who has a large following among the Siamese and Chinese resident in Siam, and who is driven by an ambitious wife who, as the intelligent daughter of one of Siam’s cleverest Foreign Ministers is thoroughly familiar with internal and foreign political machinations…

Phibun and Pridi are political opponents within the same political party. They are equally opposed to any return of the monarchy to power. They do not object to the present King because he is immature and without a following. Khuang may be forcing them into each other’s arms by the specter of Chumphot as King.

The plan was foiled by military strongman Field Marshal Pibul Songkram, who deposed the Khuang government in a coup in April 1948. Pibul wanted to keep Bhumibol on the throne, believing that the secret of his accidental killing of Ananda could be used to manipulate him.

On the afternoon of Wednesday, September 28, 1948, the King Ananda murder trial began. Royal pages But Patamasarin and Chit Singhaseni, and former royal secretary Chaliew Pathumros were accused of conspiring to kill the king in a plot masterminded by Pridi. The trial and appeals were to drag on for more than six years.

Bhumibol finally returned to Thailand briefly in March 1950 for his brother’s cremation, his formal coronation, and his marriage to Sirikit Kitiyakara. He left on June 6, a few days before the anniversary of his brother’s death. In late 1951, he at last came back to Thailand to take up his duties as king.

Bhumibol knew that But Patamasarin, Chit Singhaseni and Chaliew Pathumros had nothing to do with his brother’s murder. Yet he did nothing to save them. The three men were executed in February 1955 for a crime they did not commit.

Bhumibol changed his story about how Ananda died multiple times. In the days immediately after his brother’s death, he vehemently insisted that it was an accident. But in his testimony at the regicide trial, he abandoned this story, and shared several damaging anecdotes about Chaliew. By the 1970s, the palace had quietly dropped the claim that Chit, But and Chaliew — and Pridi — were implicated. In an interview for the BBC documentary Soul of a Nation, broadcast in 1980, Bhumibol gave a curiously evasive answer, describing the killing as a mysterious murder that was covered up by unknown powerful figures in Thailand and abroad.

During the 1990s, Bhumibol cooperated with Canadian author William Stevenson in a semi-official biography that put forward yet another story about how Ananda died. This time, the scapegoat was notorious Japanese military officer Masanobu Tsuji, who was said to have sneaked into the palace disguised as a monk. The tale was ridiculous, and there is incontrovertible evidence that Tsuji was nowhere near Bangkok when Ananda was killed.

The repeated changes in Bhumibol’s story are another clue about what really happened on June 9, 1946. He was never able to give a credible explanation for his brother’s death.

I’ve been researching Ananda’s death for years. On a rainswept evening six years ago, under a lamppost where we had arranged to meet, on a street corner near the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, a young academic gave me a document in a brown envelope and hurried off. Fear of challenging the Thai monarchy is so pervasive among those who know Thailand that he wanted to hand it over somewhere as inconspicuous as possible.

Inside was an explosive account of who killed Ananda — derived from Thai royal sources, and recorded in a private handwritten note in 1971 by Margaret Landon, wife of US diplomat Kenneth Landon.

The note is stored among the couple’s large archives at Wheaton College in the US, where the young academic found it by chance while looking through old documents. Realising its significance, he had a copy made, which eventually ended up with me under a lamppost near Russell Square.

The Landons were college sweethearts who married in 1926 and set off for Siam in 1927 as Presbyterian missionaries. They ran a Christian school the southern province of Trang for a decade before returning to the United States. Kenneth Landon was hired in 1941 by Colonel “Wild Bill” Donovan as a Southeast Asia expert for a new US intelligence agency, the Office of Co-ordinator of Information, later to become the Office of Strategic Services, and later still the Central Intelligence Agency. In 1943 he joined the State Department as political desk officer for Thailand, later becoming assistant chief of the Southeast Asia Division.

During their years in Siam, Margaret Landon had become fascinated by the life of Anna Leonowens, a woman of British and Indian descent who had been a tutor to the many wives and children of Mongkut, King Rama IV, in the 1860s. She published a semi-fictionalized account of Leonowens’ time in Bangkok, Anna and the King of Siam, in 1944. It became a sensation, selling more than a million copies around the world, and was adapted into a famous musical, The King and I, by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II. A 1956 film of the musical also became a global hit.

When World War II ended, Kenneth Landon was sent to Southeast Asia to join tense negotiations with the Thais and British over the postwar status of Siam. He spent months in the region, from late 1945 until mid-1946, and met most of Thailand’s key political leaders, plus King Ananda, recently returned from Switzerland. With excellent contacts and fluency in the language, Landon was to remain the primary State Department point-man for Thailand for years, working from his desk in Washington and making several trips to Southeast Asia.

The handwritten note by his wife Margaret was based on conversations with her friend Lydia na Ranong, a woman born into China’s aristocracy who married a Thai and became a confidante of senior royals in Bangkok.

The version Lydia na Ranong heard — probably from Prince Rangsit or his family — is extraordinary for several reasons. It totally rewrites the official story of the life of Sangwan Talapat, mother of Bhumibol and Ananda. It says that the killing of Ananda was witnessed by both royal pages, But Patamasarin and Chit Singhaseni. And it suggests that former royal secretary Chaliew Pathumros was having an affair with Sangwan, and was in her bedroom when the fatal shot was fired.

Below is a transcript of Margaret Landon’s account of the death of King Ananda. The original document can be viewed here.

June 6, 1971

Lydia — The King’s death

When she arrived in Thailand with Chok, she was received as royalty, and the King granted her the immunity from arrest without his consent that the Royal Family enjoys. She came to know leading members of the Royal Family and mentioned especially Prince Wan and Prince Rangsit. Also several others. She said that from a member of the RF she learned their version of King Ananda’s death. I surmise that the source of her [knowledge?] was Prince Rangsit, probably through members of his family.

The story begins in America where Mahidol’s mother, Phra Pan Wassa (ask Winit about use of this word. Is it grandmother of a king?) sent two girls from her entourage to study (ostensibly) but also to serve as mia noi to the prince. The old Queen was always strongly anti-foreign and was afraid of possible involvement with a foreign woman.

Mahidol fell in love with Sangwan and decided to marry her. When he wrote of his intention, his letter was not correctly interpreted, his mother thought that he was coming home to marry and, in the meantime, was taking Sangwan as mia noi.

There was consternation in the RF when the two reached Bangkok and the real purpose was discovered. I believe the old Queen was irreconcilable and that the King refused to perform the marriage but that M tricked a prince (Nagor Svarga) into doing so.

The dowager Queen’s palace was Pathumwan, and she never permitted Sangwan to cross the threshold. After her death Phumiphol conferred the palace on his mother, as compensation, but the dislike of Sangwan was continued in the RF.

Many of the details in The Devil’s Discus are correct. The OSS gave Ananda the gun with which he was killed. He had not been feeling well June 8. Both boys liked guns. (Kenneth’s story of jeep.) On the morning of June 9, Ananda was still unwell. He lay in his bed playing with the gun. Phumiphol came in. Ananda held gun to P’s head and said, “I could kill you.”

P then took it and held it to A’s head and said, “I could kill you, too.”

A said, “Pull it! Pull it!”

P did and killed Ananda.

Lydia believes the killing was accidental. This is the point that would never be cleared up.

P was appalled, horrified. The map of the palace is in the Discus, and the room where the King died is now part of the palace used to greet visiting VIPs. Lydia had a chance to see it as one of the party of a South American diplomat and the guide taking them through showed her the room & location of the bed on which the King died. The two pages later executed for the “crime” saw the killing take place since, as soon as the King awoke, they had to be in attendance.

Phumiphol ran from the room into the corridor and to his mother’s room. As he reached it a man came out of the bedroom. This, Lydia said from the version given her by the RF, was a terrible shock to P. And yet, if his mother had a paramour it seems unlikely that he did not know it. The man Lydia calls “that secretary,” obviously thinking we would know whom she meant.

P poured out his terrible story, and events began to take a course for which the RF blames Sangwan. They say that she was proud to be the mother of a King and instantly decided to suppress the truth in order to protect Phumihol and guard his right to succeed his brother, and of her determination, they say, to retain her own position.

The RF believes that she should have insisted that the truth be told. They believe the death was truly an accident, not murder, and that the people should have been so informed. After that, they say, Phumiphol should have gone into the priesthood for life and allowed the Crown to pass to some other member of the RF. This would have been an honorable course as well as an honest one. Lydia thought the RF believed the Crown would have passed to Chula. I doubt it since he was specifically excluded by King Chulalongkorn because his mother was Russian. Furthermore he had married an Englishwoman and had only one child, a daughter…

Curiously enough, the logical candidate would have been Prince Chumphot, but he, too, had no sons and only a daughter, who married a Frenchman.

Lydia says that Luang Pradit now has in his possession a letter from Luang Pibul, written a year before his death, acknowledging that the charge of complicity made against Pradit in the King’s death was false and that he, Luang Pibul, always knew this.

The story is hearsay, and some of the details are suspect — Margaret Landon clearly jotted it down in haste. The account is notably infused with contempt for Sangwan, the mother of Ananda and Bhumibol, who was born a commoner and was never liked by much of the royal family.

It cannot be considered a definitive account, by any means, but it probably comes closer to the truth than any other written document about what happened on that tragic morning that changed Thailand forever.

Any chance you’re working on a new book? One either centered on the above analysis or incorporating it to a significant degree?

"The repeated changes in Bhumibol’s story are another clue about what really happened on June 9, 1946. He was never able to give a credible explanation for his brother’s death." Good point. So, if two of those accused of Ananda's murder were eyewitnesses, why didn't they report the truth? Did they think they would be saved at the last minute as a pay-off for their silence?