6ตุลา

The story of the royalist massacre of students on October 6, 1976, which the Thai regime wants everyone to forget

Secret Siam is fully funded by readers. If you think my work is useful, please subscribe. It’s just 170 baht a month, or less if you get an annual subscription, and your support enables me to continue publishing articles on Thailand that nobody else will write.

Thank you very much to everybody who is already supporting Secret Siam.

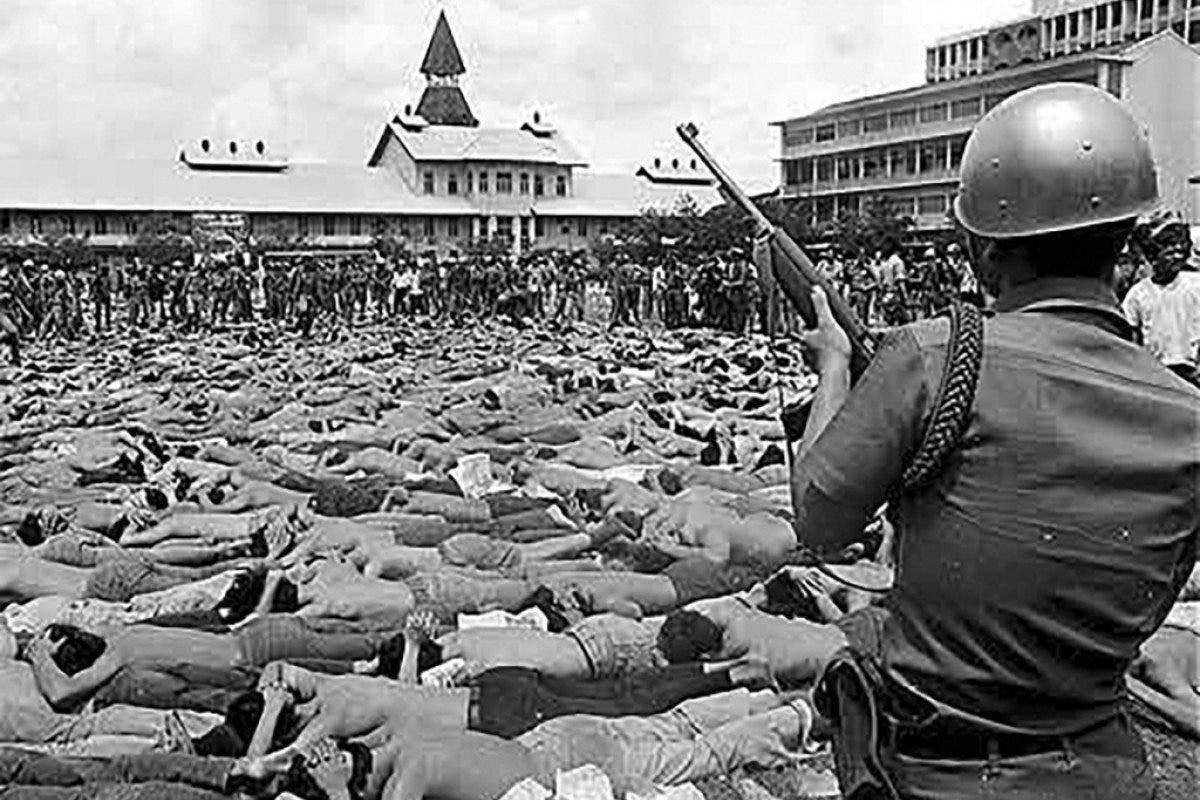

Before dawn on a Wednesday morning 45 years ago today, October 6, 1976, thousands of ultraroyalist militiamen and police armed with guns, knives, rocket-propelled grenades and anti-tank weapons launched a savage attack on student protesters in the grounds of Thammasat University in Bangkok.

The official death toll was 46 people — 41 students, two police, and three extreme-right militia members. It has long been assumed that many more students died that day, or disappeared in the weeks afterwards, probably murdered by the regime. We will probably never know the true number of victims.

Tens of thousands of students had gathered at the university overnight, for a protest against the return of ousted military dictator Thanom Kittikachorn. In the early hours of October 6, police and paramilitary forces surrounded the campus. Some of them began firing randomly into the grounds of Thammasat. A student security post at one of the gates to the campus was set ablaze around midnight.

The first deaths inside Thammasat were at 5:30 in the morning when a M79 grenade was fired into the campus. As historian Thongchai Winichakul, who was one of the student leaders inside Thammasat, wrote in his book Moments of Silence published last year: “Four people were killed instantly. Dozens were injured. The massacre had begun.”

Five years ago, Thongchai talked to the BBC about the events of that day.

Thongchai, who was in control of the loudspeaker at the protest stage, used it to plead with the police and paramilitaries to stop the killing. As he wrote in Moments of Silence:

“Please, my police brothers, please stop shooting. Please. We gather here peacefully and unarmed. Our representatives are negotiating with the government right now. No more bloodshed, please. We beg you. Please stop shooting.”

I remember that I kept repeating those words hundreds of times that morning — the same words, over and over, so that I did not need to think, because I could not think. From the back of the stage, as the voice of the demonstration, I tried to keep some semblance of order alive as long as possible. I could not think of anything else to do…

I did not feel brave. I was terribly frightened. Only my awareness of those thousands under siege inside Thammasat kept me from abandoning the stage and running away.

With the university surrounded, the thousands of desperate students inside Thammasat had no way to escape. Most sought shelter inside buildings in the campus, as the gunfire and grenade attacks intensified. Some tried to flee by diving into the Chaopraya river, but instead of being helped they were fired upon by police and navy patrol boats.

Around 7:30 in the morning, the attackers commandeered a bus to smash their way through the university gates. Thongchai described what happened in Moments of Silence:

Once inside Thammasat, the police initially advanced slowly.

At first, I could see that they crawled while shooting at students who were trapped inside the buildings. Later, probably realizing that no one was offering any significant resistance, the police got up on their knees, taking more shots as they lined up in two rows along the small road in front of the Law School Building. Later, probably realizing that there was absolutely no resistance, the police got to their feet and walked confidently, firing freely at various targets they could see.

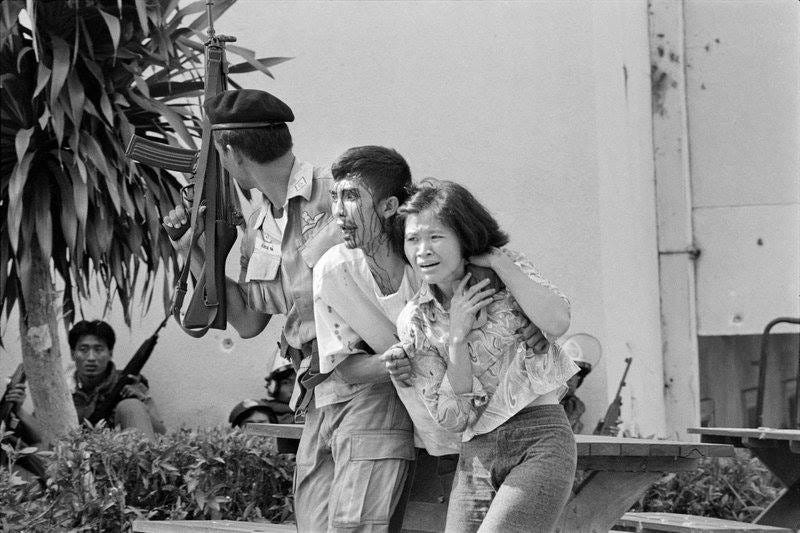

Students inside the grounds were beaten, stripped and forced to lie on the ground for hours, with their hands on their head. They were the lucky ones. Protesters who had tried to escape through the front gates of the university, or who emerged to try to negotiate a ceasefire, were set upon by the mob.

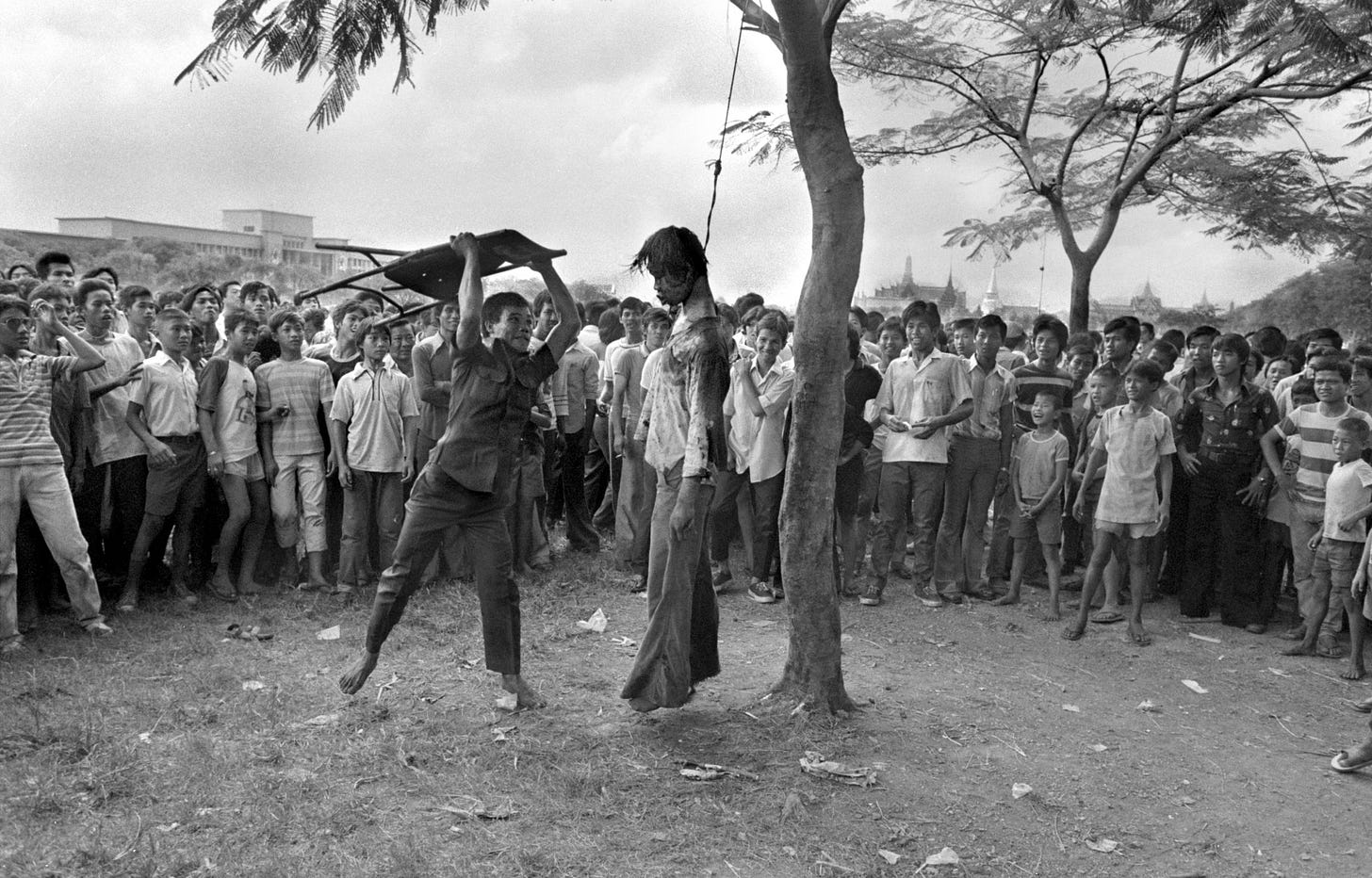

Many were beaten to death. Others were shot. Some were hanged from trees in Sanam Luang, the royal park and cremation site adjacent to the Thammasat campus. Several were doused in gasoline and set ablaze. One female student was sexually violated with a stick after being shot.

Even once they were dead, the corpses of the students suffered further violence as police and ultra-rightist thugs mutilated and abused them, gouging out their eyes and slitting open their bodies.

Yet Thailand’s elite seems determined that it should be forgotten. It is barely mentioned in school history books. No official memorial to the dead has ever been erected. The only people arrested and jailed after the violence were 18 students who survived the massacre (including Somsak Jeamteerasakul and Thongchai, both now renowned historians of Thailand). None of the killers ever faced justice.

“It’s as if it never happened, or as if its only value was to teach people how to forget,” wrote Thongchai in a letter to students 20 years later.

The attitude of Thailand’s elite was exemplified by Prime Minister Samak Sundaravej in an interview with Selina Downes of CNN in February 2008. Samak was an ultra-rightist politician who had used his radio show to encourage the massacre of the students in 1976. But 30 years later he not only denied that he had been involved in stirring up the violence, he even tried to pretend that it had never even happened at all.

“Only one guy died in Sanam Luang,” he said, becoming increasingly abusive towards Downes. “Nobody died in Thammasat University.” Here is an excerpt of the interview, with some footage of the massacre added by me.

Why are Thailand’s elite so keen to forget October 6? One reason is national shame at the savagery and brutality of the events that day. As Thongchai says: “The brutality of that Wednesday morning was far beyond anybody’s anticipation. Our morals and political optimism had held our imagination in check. But reality is never kind. That morning’s stark events remain incomprehensible to many people’s minds.”

Many Thais feel deep embarrassment at images like the Pulitzer Prize-winning pictures taken by Associated Press photographer Neal Ulevich during the massacre. The most famous of the photographs shows a dead protester who had been hanged from a tree, being battered with a folding metal chair by a grinning militiaman as a large crowd laughs and cheers.

It is a haunting photograph, not just because of the shocking central image, but also because of the unsettling smaller details that emerge as you study it more closely. The rapt faces of the crowd. The joyful glee on the face of the little boy. The rope tied to the other tree in the background, where beyond the frame of the photograph, another corpse is hanging, and another crowd is gawking and cheering, as all around on the royal park and cremation site known as Sanam Luang, other students are being beaten, shot, sexually assaulted, mutilated, murdered and burned alive.

Another detail in the photograph provides a clue about why the October 6 massacre is regarded as an event that must not be spoken about. On the horizon, beyond the awful scenes on Sanam Luang, are the spires of the Grand Palace and the Temple of the Emerald Buddha. The savagery of October 6 unfolded within sight of the symbolic centre of royal power in Thailand, and the monarchy was intimately involved in the events that led to the hideous brutality that day. This is what has made the massacre a taboo subject for Thais.

“The political ramifications of truth may be unthinkable, literally, for Thai society, since several individuals and institutions which command power and respect in the society, namely the monarchy and the Buddhist sangha, had been involved in the conspiracy that led to the killing,” observed Thongchai in 2001. “Truth might have been devastating to the society and to those who try to get to the truth themselves. Silence is therefore mostly self-imposed, either out of fear or out of concern for the unthinkable consequences to the country. The massacre of 1976 was, so to say, in the realm of the unspeakable, of silence. Its full history is probably impossible to write under the present system of ‘Democracy with the Monarchy as the Head of the State’.”

In October 1973, students and workers in Bangkok had risen up against the hated military dictators who ruled the country — field marshals Thanom Kittikachorn and Prapas Charusathien, and Narong Kittikachorn who was the son of Thanom and son-in-law of Prapas — who were collectively known as the “three tyrants”. More than 70 people were killed as the junta brutally tried to crush the mass protest against their rule.

At a critical moment, on the morning of October 14, 1973, some students fleeing the violence sought refuge in Chitralada Palace, the residence of King Bhumibol Adulyadej, and were given sanctuary by the royal family. Bhumibol was also negotiating with rival military factions, seeking a compromise that would give the protesters some of what they were demanding. But events moved faster than the king had anticipated.

Emboldened by the belief that Bhumibol was on their side, the protesters continued their resistance, and by evening the three tyrants had fled the country. For the first time since 1947, Thailand was free of military rule.

Official accounts of the events of 1973 give Bhumibol all the credit for restoring democracy to Thailand. It became one of the central myths of modern royalist propaganda. In fact, Bhumibol was deeply uncomfortable with democracy. With a communist insurgency gathering strength in northeast and southern Thailand, Bhumibol began to believed that the Thai monarchy was facing an existential threat to its survival.

His wife Queen Sirikit and their son Crown Prince Vajiralongklorn were even more extreme than Bhumibol in their disdain for democracy and support for far-right elements of Thai society. Thailand’s royal family began actively working to undermine democracy.

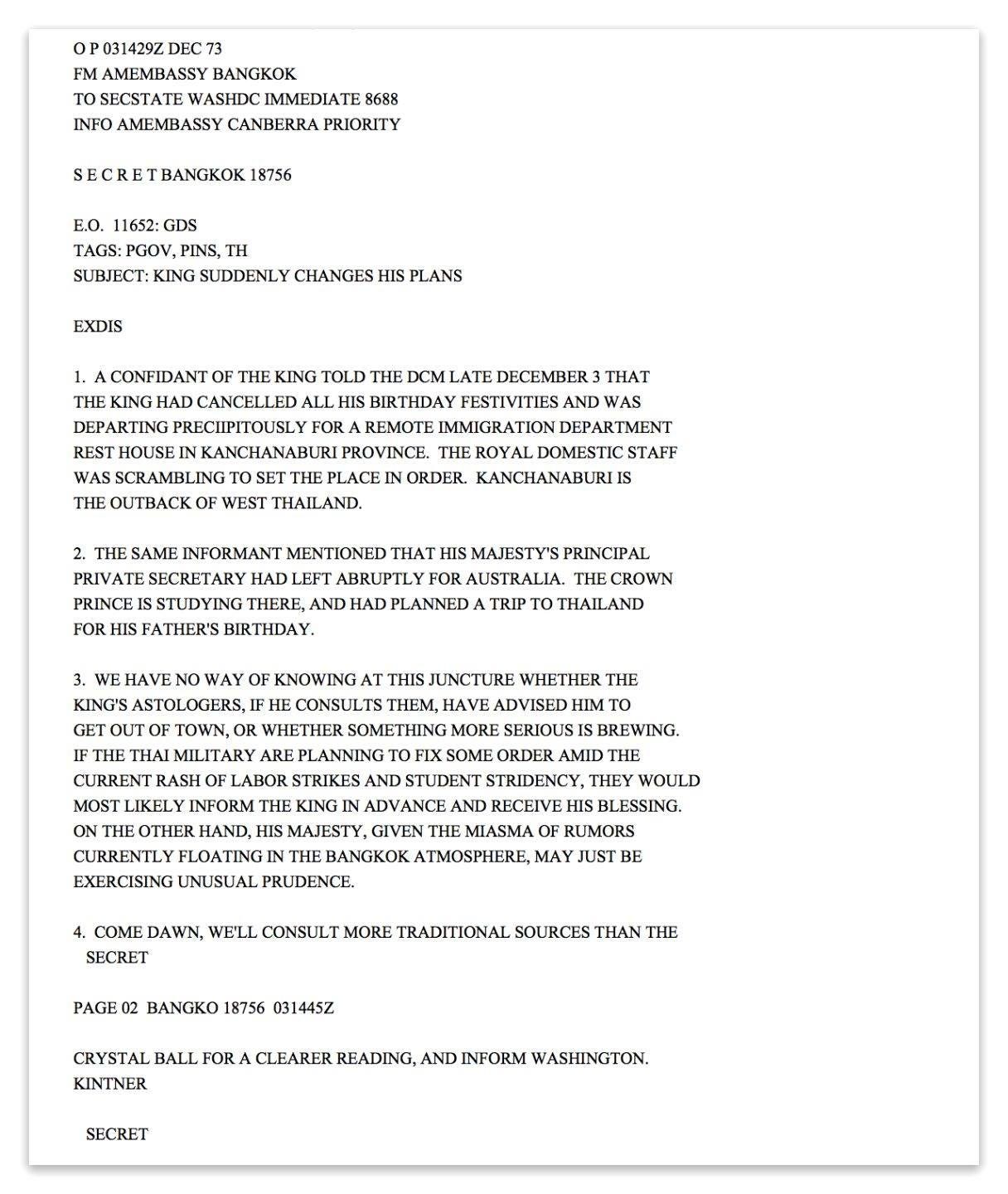

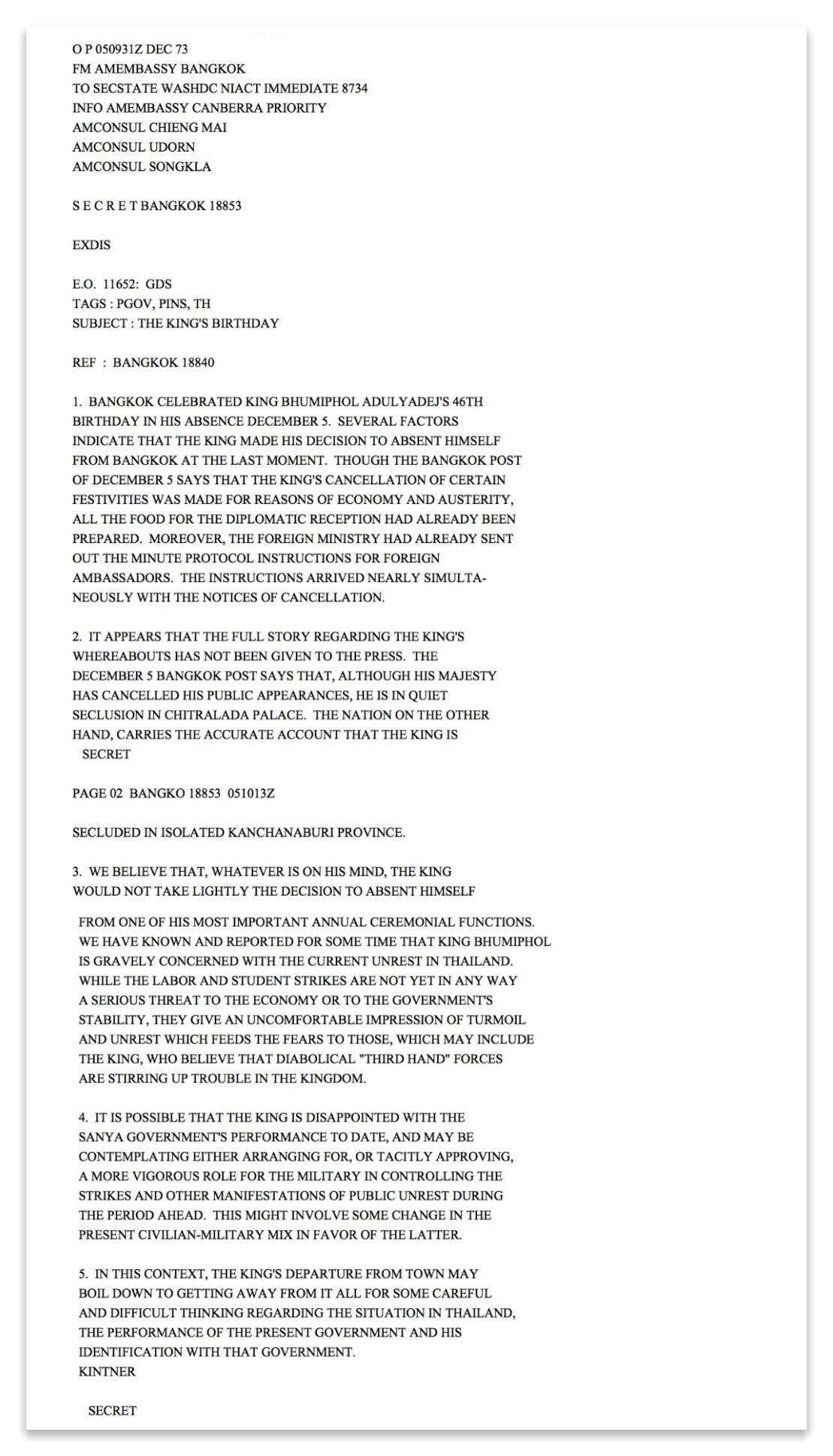

In December 1973, according to a secret cable to Washington from U.S. ambassador William Kintner, Bhumibol suddenly became so afraid about something that he suddenly abandoned the celebrations planned for his birthday in Bangkok and fled to a remote immigration department rest house in Kanchanaburi province.

Meanwhile, the king’s principal private secretary hurriedly rushed to Australia where Vajiralongkorn was at military college. The crown prince had become increasingly unpopular in Thailand, worsening relations between Bhumibol and Sirikit as they argued over how to handle him.

No sensible explanation for Bhumibol’s sudden panic was ever given. In another secret cable on the king’s birthday, December 5, 1973, Kintner speculated that the episode was more evidence that Bhumibol was becoming increasingly paranoid.

“We believe that, whatever is on his mind, the king would not take lightly the decision to absent himself from one of his most important annual ceremonial functions,” Kintner wrote. “We have known and reported for some time that King Bhumiphol is gravely concerned with the current unrest in Thailand. While the labor and student strikes are not yet in any way a serious threat to the economy or to the government's stability, they give an uncomfortable impression of turmoil and unrest which feeds the fears to those, which may include the king, who believe that diabolical ‘third hand’ forces are stirring up trouble in the kingdom.”

The fall of Saigon in Vietnam and the victory of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia in April 1975 were followed by the overthrow of the royal family of Laos by communist Pathet Lao insurgents in December. Undoubtedly feeling increasingly besieged and imperiled, the palace sponsored and supported the creation of ultra-right-wing nationalist militias in the 1970s, most notably the Village Scouts and Red Gaur, as well as a secretive extremist network of officials, Navapol. By 1976, Sirikit in particular was openly condemning pro-democracy activists and expressing support for the security forces to run the country.

Thailand’s royal family genuinely believed they could be overthrown by communists, as the monarchies of Cambodia and Laos had been. They were bewildered with the sudden freedoms unleashed by the restoration of democracy in Thailand, and resented the erosion of social hierarchy and order.

In 1975, Charles Whitehouse took over from Kintner as U.S. ambassador to Thailand. In his first meeting with the king, described in a confidential cable, Whitehouse said Bhumibol seemed depressed and anxious.

“The king welcomed me to his country and said that I was arriving at a particularly difficult and dangerous moment not only in the history of Thailand but in the broader context of world affairs,” Whitehouse wrote, adding the king was also worried about opposition to the monarchy. “There was a small but very vocal minority which considered people like himself to be dinosaurs but they had no real appreciation of the needs of the kingdom... I gained the impression from the king's manner, as well as from his remarks, that he is profoundly concerned over the external/internal menace he perceives to the security of the kingdom.”

During the Vietnam war, Thailand had been a crucial ally of the United States, which established vast military bases in the kingdom. But in 1976, partly thanks to pressure from students, American forces were withdrawn. This caused deep disquiet in the palace.

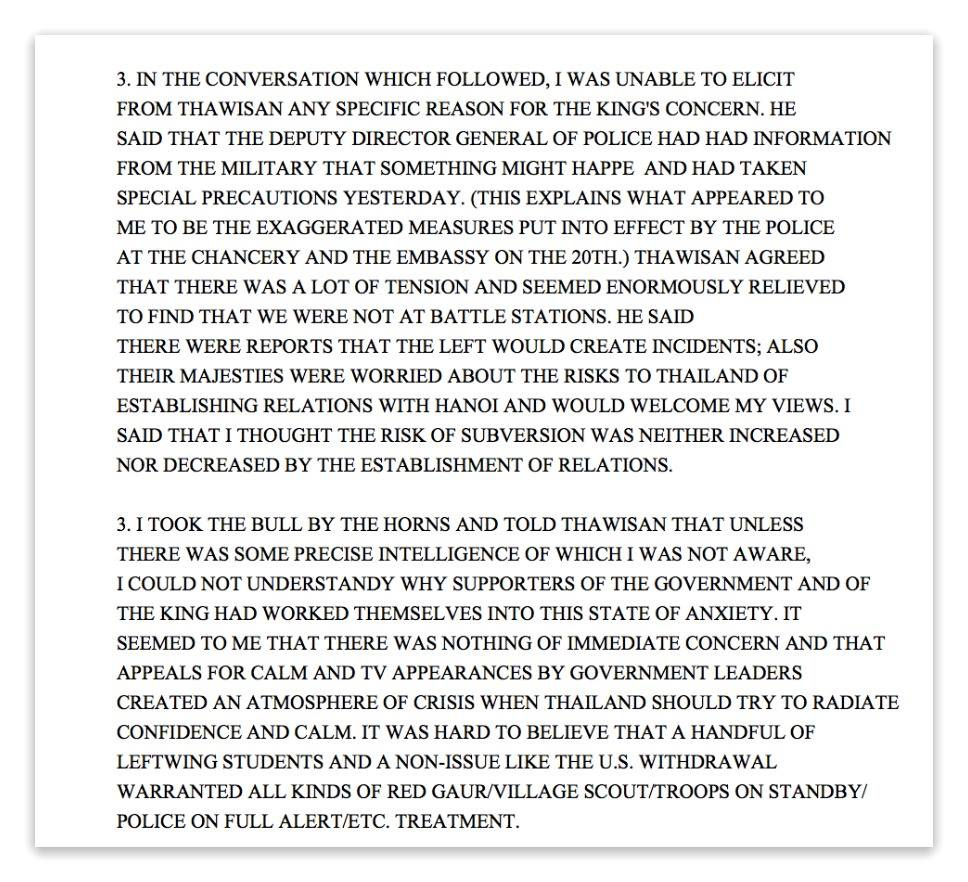

In a secret cable from July 1976, Whitehouse describes an atmosphere of panic among Thailand’s royalist elite as U.S. troops left the country. On July 21, Whitehouse was visited by Bhumibol’s private secretary Thawisan Ladawan and Sirikit’s brother Adul Kitiyakara. Both were in a state of extreme agitation, fearful that Thailand was facing calamity. Whitehouse was perplexed.

“I took the bull by the horns and told Thawisan that unless there was some precise intelligence of which I was not aware, I could not understand why supporters of the government and of the king had worked themselves into this state of anxiety,” he wrote. “It seemed to me that there was nothing of immediate concern and that appeals for calm and TV appearances by government leaders created an atmosphere of crisis when Thailand should try to radiate confidence and calm.”

In his cable to Washington, Whitehouse noted that the paranoia in the palace was worsening Thailand’s divisions: “I am convinced that the palace has worked itself into a state of nerves and hope that Thawisan’s version of our conversation will bring some perspective into the palace group, which by its recent actions has tended to polarize public opinion rather than inspiring the confidence without which conditions in Thailand can only get rapidly worse.”

As Benedict Anderson observed in Withdrawal Symptoms, his brilliant analysis of the context of the Thammasat massacre, the palace was in a state of “almost cosmological panic”.

Thongchai describes the atmosphere of the mid 1970s in Moments of Silence:

The 1973 uprising sparked a euphoria and energy for political freedom and social change. From 1973 to 1976, social move- ments for various causes erupted, demanding dramatic reforms in virtually all aspects of Thai society and undermining the power of some established institutions.15 For instance, in 1974-1975 labor strikes occurred, on aver- age, twice a day.10 The thirst for new ideas was insatiable, especially for those that had been forbidden under military rule such as Marxism and Maoism. Many individuals and movements-of students, labor, and farmers -became radicalized. They demanded radical changes in democracy, land reform, worker's rights and welfare, education, capitalism, and so on. In the view of those in power, and increasingly of the general public too, these abrupt changes brought chaos and disorder. One crisis broke out after another, both within parliamentary politics and on the streets. Tensions intensified in almost every sector of society affecting people in all walks of life.

Bhumibol and Sirikit were not only rattled by paranoia themselves, but they sought to imbue the same sense of menace throughout the country though their explicit support for right-wing secret societies and militias like the Village Scouts and Krating Daeng, whose members were told they were fighting for the very survival of the monarchy and the kingdom.

The tensions and disagreements in the royal household between Bhumibol and Sirikit only made the toxic atmosphere in Thailand worse.

In September 1976, exiled former military ruler Thanom returned to Thailand with palace support and was ordained as a monk at Wat Bornivores, regarded as the personal temple of the Chakri dynasty. This was a deliberate provocation by the palace to try to undermine the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Seni Pramoj.

Students responded with several mass rallies. By early October, thousands of protesting students had gathered inside the walled campus of Thammasat University on the Chaophraya riverside north of the Grand Palace.

On October 5, photographs of a mock hanging staged by protesting students inside the campus were published in some Thai newspapers. The student pretending to be hanged looked uncannily like Vajiralongkorn, and it was alleged by the extreme right and ultra-royalists that the protesters had been calling for the crown prince to be executed. Students instead that it had nothing to do with attacking the monarchy and was intended to dramatise the lynching of two protesters in Nakhon Pathom a week earlier.

Suchada Chakpisuth, one of the students who took part in the mock hanging, described the reaction in a Thai article that has been translated into English by Tyrell Haberkorn for the LA Review of Books. She had returned home to the shophouse where her family lived from the Thammasat campus on the afternoon of October 5:

It was late afternoon, and I was still in my university student uniform. I turned on the radio as usual, to listen to music as I lulled my six-month-old niece to sleep in a canvas chair behind the shop. But things were not as usual. A live broadcast from Yan Kraw radio station came on, during which the Department of Public Relations announced that Thammasat University students had performed a play lynching the crown prince.

The broadcast said that the students were communists who harbored evil intentions to destroy the nation and topple the monarchy. I suddenly leapt up and spoke back in my heart: “Not true. You are lying. It is you who harbor evil intentions to destroy the nation.” My parents were working in the front of the shop, so I left through the back gate and returned to the university.

Spurred on by the hysterical radio broadcasts accusing the students of lèse majesté and urging “kill them, kill the communists”, thousands of royalist paramilitaries massed outside the campus by the evening of October 5. Early the next morning, the killing began.

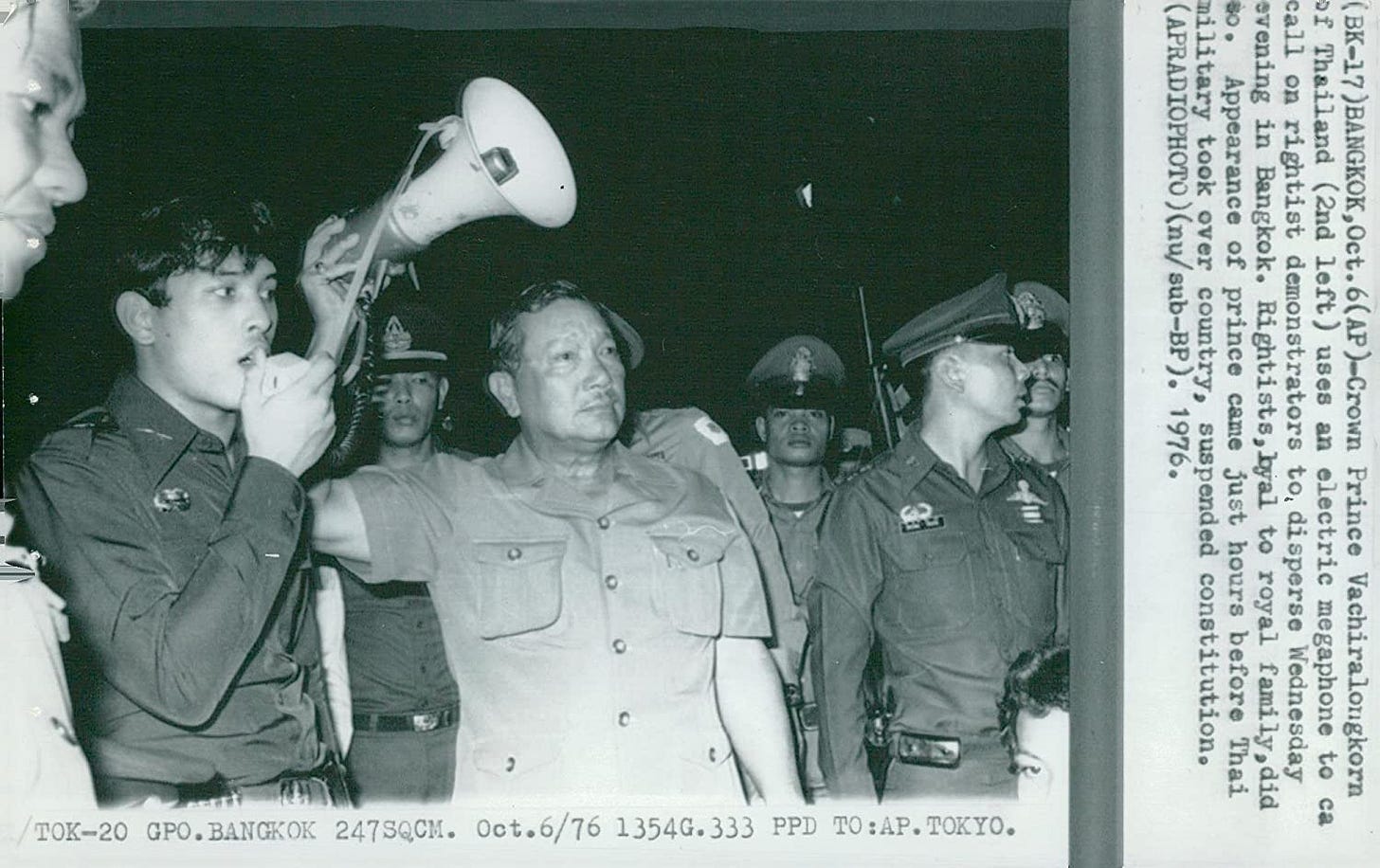

Vajiralongkorn was summoned back from Australia a few days before the massacre, on October 2, 1976, and his role in the events of 1976 remains unclear. He was seen giving support to soldiers and police on October 6 and was at Royal Plaza during the afternoon urging the mob to disperse after the violence was over.

In the hours after the shocking violence at Thammasat and Sanam Luang, Bhumibol intervened to install a far-right government after the coup, under Supreme Court judge Tanin Kraivixien. Thai democracy had once again been crushed — with the full support of the king.

But while the palace had been seeking a pretext for months to remove the democratic government, and had set events in motion by allowing the dictator Thanom to return to Thailand, Bhumibol had not anticipated the scale and savagery of the violence that erupted on October 6. In the days afterwards he was deeply concerned — not because of the suffering of the victims and their families, but because of the damage to his image.

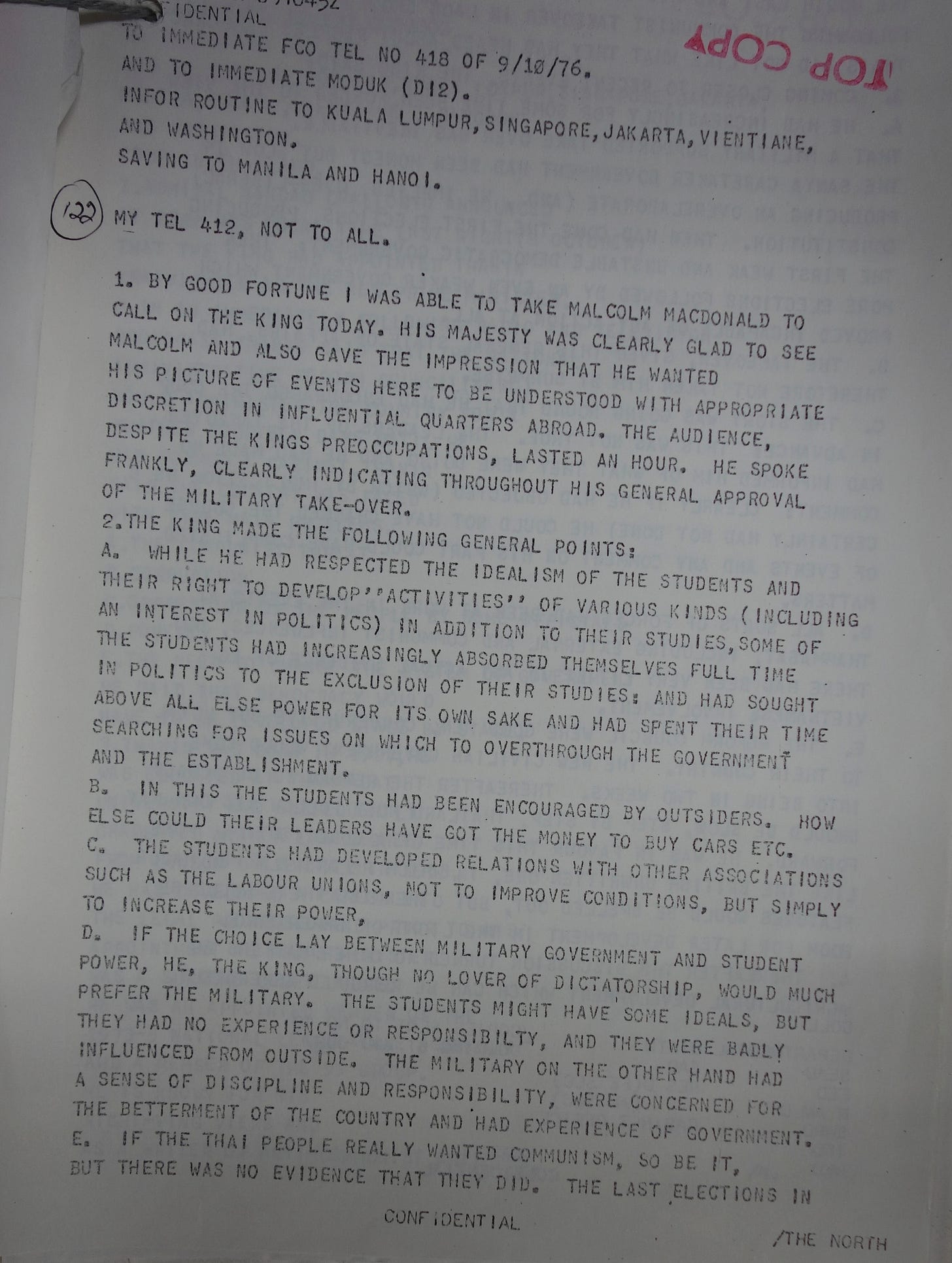

Three days after the massacre, British ambassador David Cole took senior UK diplomat Malcolm Macdonald for an audience with Bhumibol.

The king spoke to them for an hour, “clearly indicating throughout his general approval of the military takeover”, according to a confidential cable written by Cole after the meeting. Bhumibol blamed the students for the violence, saying they had become power-hungry and had been encouraged by sinister outside forces — “how else could their leaders have got the money to buy cars etc?”

The king stated clearly his preference for dictatorship over democracy.

“If the choice lay beween military government and student power, he, the king, though no lover of dictatorship, would much prefer the military. The students might have some ideals, but they had no experience or responsibility, and they were badly influenced from outside. The military on the other hand had a sense of discipline and responsibility, were concerned for the betterment of the country and had experience of government.”

Bhumibol denied that he had encouraged the coup in advance, but admitted that the forces seeking to overthrow Thai democracy had kept him informed about what they were planning, and he did not intervene to stop them.

Ten days later, US ambassador Whitehouse had lunch with Bhumibol’s private secretary, who told him the king was still fretting that his image had been tarnished.

“Thawisan said the king had asked him to get my advice on how Thailand could overcome the false impression which had been given in Europe and America of recent events here. He said the king hoped that there was some way by which the U.S. could explain that the change of government had been brought about as a result of the weakness of the Seni government and the provocative actions of communist-inspired students,” Whitehouse reported in a secret cable.

“I said that frankly I could see no way of overcoming the worldwide impact of the photo and television coverage of the events of October 6th at Thammasat university. Friends of Thailand could only hope that the kind of administration which the new government would provide and the sort of leadership it would give the country would erase the images of brutality which have been so widely publicized.”

In the months and years after the awful events of October 6, 1976, royalist propaganda became increasingly pervasive and extreme. Criticism or sensible debate about the monarchy became impossible. As part of the propaganda effort, the BBC produced a two-hour documentary called Soul of a Nation that glorified Bhumibol and the Thai royal family, portraying them as working tirelessly to develop the kingdom and combat communism.

The documentary briefly discussed the violence of 1973 and 1976, with Bhumibol denying any role in the Thammasat massacre and insisting he was above politics. Here’s an extract:

But the king wasn’t telling the truth. He had played a central role in the developments that led to the murderous violence at Thammasat University that day. And somebody in the palace must have played a role in giving approval for the massacre. It is inconceivable that those who led the assault on Thammasat would have done so unless they had received a signal that they would have royal protection.

“To this day it has yet to be revealed who or which group actually planned and endorsed the October 6 massacre,” says Paul Chambers, an academic who specialises in the study of the Thai military. “The planning suspects could not have included the First Army Region commanders because they were planning the coup for that evening. But the likely culprits remain elements leading the Supreme Command; the Border Patrol Police; and the Young Turks army faction — most probably all together. But who led them in the planning?”

That question remains unanswered. Bhumibol claims he was informed of the plans of the coup plotters but seemed surprised by the massacre. But Sirikit was also interfering in Thai politics independently of her husband, and Vajiralongkorn’s unexplained return from Australia on October 2 is also intriguing. Why did he suddenly come back to Bangkok, and why was he in Royal Plaza on the afternoon of October 6 after the massacre, telling the mob it was time to disperse?

Over the decades that followed, the palace tried to erase the massacre from memory. The trees that students had been hanged from were chopped down. Discussion of the violence was discouraged. The cult of King Bhumibol became ever more extreme. Thailand remained trapped in a toxic cycle of coups and corruption. Nothing was learned from the events of October 6.

Yesterday, on the eve of another commemoration of the massacre, Thammasat University closed down its campus beside Sanam Luang, claiming that this was to try to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

It was just another lie, a clumsy attempt to try to stop people thinking about what happened 45 years ago, and pretending it never happened and the monarchy is on the side of the people.

But by now, most Thais are starting to understand that everything they were told was never true.

Today, let’s remember the people who died 45 years ago, and don’t give up fighting for what they were fighting for — real democracy in Thailand.

Secret Siam is fully funded by readers. If you think my work is useful, please subscribe

I also went to the commemoration Ceremony at Thammasat Traprachan Campus This Year, Even if the headmaster was announced that prohibits the ceremony to be set inside the campus due to the COVID-19 pandemic. So the ceremony was jam-up a lot but many people in many ages have come more than any years in the past!!! That was Terrific krub..

Now, according to the Voice TV, there has some interesting efforts to push October 6 Massacre incident to the ICC (International Criminal Court) to consider and make a guilty judgement to Behind Curtain mastermind of the massacre, Ajarn Somsak Jeamteerasakul said there is no hope to it but, I think it is a good and interesting move for psychology war krub…

October 6, I think We thais have to moaning and commemorating it for the rest of ours short human life 1. For Praise the Sacramento Heroes and their relatives. 2. For Lesson Learning to Prevent the Tragedy to be occur again in the nearly future krub. Khun Andrew

😿❤️🌎👍

I think many readers will tend to take the view that a significant part of the historic reason for not seeking answers to the Thammasat massacre is that culturally there isn’t a strong inclination to dig for truth. Anyone who’s been exposed to the typical customs and found him or herself attempting to get to the bottom of a subject will attest to eventually realising that delving into detail just isn’t something they do, even in matters of importance.

That notwithstanding, the fact that there was no significant inquiry into the incident, nor redress for the state’s actions says everything about the way in which Thailand, under Bhumibhol’s regime, treated ordinary people — with utter contempt. All were seen as unquestionably guilty if not overtly playing the sycophantic, monarchy-idolising game. Though clearly he knew he had taken a step too far, recognising that the monarchy’s prestige was in doubt and its future might be precariously at stake — Vajiralongkorn’s sudden return being an indicator of the perceived chaos. No small wonder Vajiralongkorn has turned out to be such a vicious and violent character himself with such a low regard for people — he’s the result of an upbringing of stamping out all who seek a better future than the Chakris are willing to offer.