Remembering the disappeared

My friend Wanchalearm Satsaksit was kidnapped and probably murdered in Cambodia. This is the story of what happened to him, and the nine other dissidents abducted by the Thai regime.

Around quarter to five in the afternoon on June 4, 2020, Wanchalearm Satsaksit left his apartment in the Mekong Gardens complex in Phnom Penh to buy some meatballs from a street food stall, while chatting to his sister Sitanun on his mobile phone.

Suddenly, several armed men grabbed him and forced him into a dark coloured Toyota Highlander which sped away.

Sitanun heard the commotion over the phone.

“I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe,” shouted Wanchalearm, who was known as “Tar” and was 37 years old.

For the next 30 minutes, Sitanun stayed on the call, hearing only muffled sounds. Then the line went dead.

Wanchalearm Satsaksit has never been seen or heard from again.

He was the tenth Thai dissident to vanish from Southeast Asian countries over the past five years. The bodies of two of them have been found. The rest remain missing and are assumed to have been murdered.

Wanchalearm was my friend. This is the story of what we know about what happened to him, and to the nine other Thai dissidents who have vanished abroad since 2016.

At the start of 2014, I went to live in Phnom Penh. I was working on my book A Kingdom in Crisis and wanted somewhere inexpensive to live in the region while I wrote it. We found a house on Street 21, also known by its old French name Rue Abdul Carime, with a small garden overflowing with trees hung with baskets of tumbling orchids, and a couple of big ceramic pots filled with water and dozens of tiny brilliantly coloured fish.

Rue Abdul Carime was where I finished my first book, and saw it published, and where my son Charlie took his first steps and began to talk. I loved it there and will never forget my time in Phnom Penh.

I’m a criminal in Thailand, but Phnom Penh was a safe haven back in those days, even though it’s a lawless place.

During his time as prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra had developed a rapport with Cambodian dictator Hun Sen, and they remained allies even after he was overthrown. Thai dissidents were able to live openly in Phnom Penh without fear of extradition.

I never revealed exactly where I lived, and our house was hidden behind high metal gates. For most of our time in Phnom Penh I never felt threatened or under surveillance. We knew all the tuktuk drivers who slept in their vehicles on the street outside, and they would have warned us if they saw anything sinister.

Among the most prominent Thai exiles in Phnom Penh was Jakrapob Penkair, a former cabinet minister who fled Thailand in 2009 after being charged with lèse majesté. He lived in a large compound on the outskirts of town, and was always a gracious host with many interesting stories to tell. Another dissident I got to know was film director Neti Wichiansaen, widely known on social media as Pruay Saltihead, who escaped Thailand in 2010 while also facing charges under Article 112.

On May 22, 2014, a military junta led by Prayut Chan-ocha and Prawit Wongsuwan seized power in Thailand, overthrowing the elected prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra in an illegal coup.

The junta began summoning Thai activists and dissidents for so-called “attitude adjustment” in military detention.

Wanchalearm was a democracy activist who worked for the youth wing of the Pheu Thai Party and secretly ran a highly popular Facebook page jokingly called “I will definitely get 100 million baht from Thaksin” which mocked the military and regularly published leaked information.

At the time of the coup, he was staying with the family of his girlfriend Prakaidao, daughter of veteran activist Somyot Pruksakasemsuk who was serving a long prison sentence for lèse majesté.

According to Prakaidao, the military somehow traced some of Wanchalearm’s online criticism of the coup to an IP address at the Pruksakasemsuk family home, and raided the house on May 25. Prakaidao and her mother Sukanya were arrested and detained for 24 hours at the Army Club.

Wanchalearm got away by jumping over a wall, and caught a flight from Don Muang to Kuala Lumpur later the same day. This was the start of his life in exile.

He made his way to Phnom Penh, and I first met him a couple of weeks after his escape.

Meanwhile, as the junta tightened its grip in the weeks and months after the coup, banning all dissent and detaining anybody who stood up for democracy, scores more activists and dissidents decided to flee Thailand. The only safe route to freedom was through Cambodia.

Laos was a dangerous dead end — the oppressive Lao regime barely tolerated Thais escaping the junta, and once there it was almost impossible to get to a safe third country. Going through Myanmar was equally difficult — the Thai junta had longstanding links with the Burmese military.

Cambodia was the only realistic way out. The border between Thailand and Cambodia is extremely porous — it’s easy to cross between the two countries informally at countless remote spots, and if you don’t want to have to trek through the wilderness, many of the vast casinos at border towns like Poipet actually straddle the frontier and are happy to facilitate people moving illegally between the two countries, to enable high-rolling Thai gamblers to bring their winnings back without official scrutiny. It’s also fairly easy to move informally between the two countries by sea.

Several well-known dissidents including Somsak Jeamteerasakul and Suda Rangkupan escaped to Cambodia during this period. Some European countries — above all, France — were willing to issue laissez passer documents to Thai activists so they could fly to Europe and claim political asylum even after the junta had cancelled their passports.

Phnom Penh became a magnet for Thai exiles. Thai journalist Nanchanok Wongsamuth wrote a good story on the Phnom Penh exile community in June 2014, and the New York Times also reported on the exodus to Cambodia.

I saw Wanchalearm often during 2014. He was great company — smart, funny, brave and kind, with a big smile, always ready to help others. I never heard him say anything mean or cruel, even about the junta. He didn’t hate anybody. He just wanted to help Thais get democracy and equal rights for all.

Sometimes he would disappear for a few days, telling me he had to go to the Thai border, or to Sihanoukville to meet an incoming boat, and gradually I realised that once he had reached Phnom Penh, Wanchalearm had soon become one of the key people running the underground railroad that helped other Thais escape to safety in Cambodia.

The underground network was funded by Thaksin, and facilitated by a powerful Cambodian godfather known as Huad who controlled large swathes of the border regions and was fluent in both Thai and Khmer. It was tacitly approved by Hun Sen, and it involved officials at all levels of the Cambodian government.

Dissidents who crossed into Cambodia illegally were able to get entry stamps in their passports to make it look as if they had arrived legitimately, and even if their passports had been cancelled they were allowed to fly out of Pochentong Airport to safety in Europe, the US, Australia or New Zealand.

There were broadly two types of people using the network to flee Thailand. The first group was the political dissidents — people like Somsak and Suda.

The second group was people who had committed violent attacks against the far-right PDRC protest movement. Thaksin had (stupidly and unforgivably) sought to undermine the PDRC by making it known that if people used violence against them, they would be paid and protected. This was the reason for the gun, bomb and grenade attacks on PDRC rallies in 2013 and 2014.

All of the attacks were relatively small-scale, but several people were killed and dozens wounded during this period. Thaksin kept his word and the perpetrators were helped to flee to Cambodia.

Most of those who escaped Thailand were accommodated at apartment buildings in the east of Phnom Penh owned by the Khmer border gangster Huad and his associates, including Mekong Gardens.

The Chroy Changva district where the apartment buildings were located is across the Tonle Sap River from downtown Phnom Penh so it was a relatively inconspicuous location.

The initial safe house for arriving exiles was a large brothel owned by Huad, the multi-storey Washington Hotel, about five minutes walk from Mekong Gardens. It had a fishbowl full of women in underwear on the second floor and was popular with Asian tourists and rich Cambodians. It was a good hiding place for people who didn’t want to be found.

The dissidents who had been fighting for democracy and the paid perpetrators of violent attacks had little in common, and indeed tended to profoundly disagree about the methods used to advance their goals.

The network running the underground railroad did their best to keep the two groups separate, in different apartment buildings, but there were a lot of arguments and tensions. Managing the situation was not an easy task.

Wanchalearm didn’t believe in violence, but he did his best to help everybody who was escaping Thailand, and didn’t judge them. He just tried to get them to safety.

Towards the end of 2014, a friend of mine suddenly found himself facing an extremely dangerous situation in Thailand, and had to escape the country. I put him in contact with Wanchalearm, who was able to get him safely to Cambodia, and then onwards to claim asylum in Europe. I can’t tell the full story of this episode yet, because my friend is not ready to talk about it publicly, but all I can say is that Wanchalearm was there when we needed him, and went out of his way to help people in danger.

Soon afterwards, I left Cambodia. It was starting to feel unsafe for my family, particularly after the recent events I had been involved with. The generals in the Thai junta were working hard to ingratiate themselves with Hun Sen, and it seemed like Thaksin was probably decisively defeated. The ever pragmatic Cambodian dictator decided it made more sense to work with the Thai regime rather than defy it.

Phnom Penh had become infested with Thai agents and spies, keeping an eye on the dissident community. A few times, when meeting Thai friends in restaurants and bars, groups of men with short haircuts would be sitting nearby, watching us intently.

It was time to go. At the end of 2014, we left our house in Phnom Penh and moved to Scotland.

All of the exiles knew that things were becoming more dangerous for Thai dissidents in Southeast Asia, but none of us realised how bad it was going to get.

The first warning signs were in Laos. A few decades ago, Laos was regarded as a hostile state to Thailand and a vassal of Vietnam, but in the 21st century political alignments in Southeast Asia have changed. China’s influence is becoming dominant everywhere, and old regional enmities are fading away, replaced by mutual support among authoritarian regimes to assist each other’s efforts to crush dissent.

Meanwhile, as King Bhumibol’s health worsened dramatically in 2016 he became unable to exert any more influence to control his son Vajiralongkorn. The junta acquiesced to whatever Vajiralongkorn demanded, and the crown prince and his henchmen decided to start murdering dissidents based abroad to try to strike fear into opponents of the monarchy.

Some of those who fled to Laos after the 2014 coup, including Somsak Jeamteerasakul, realised it was a hostile environment and managed to get to Cambodia where they were safer. But others got stuck in Laos, including Ittipon Sukpaen, known as DJ Sunho, a Red Shirt activist from Chiang Mai.

Sometime in late June 2016, Ittipon was seized by black-clad men in Laos. His trainers and motorbike were found near his home. Credible information suggested he’d been abducted by Thai soldiers and taken across the border to detention at the 36th Army Circle base in Phetchabun, but after that the trail went cold. He has never been heard from again.

In July 2017, 10 armed men dressed in black, wearing balaclavas, and speaking Thai, seized dissident Wuthipong Kachathamakul, also known as Ko Tee, at his house in Vientiane where he had been living in exile.

Ko Tee, his wife, and a friend who was also in the house were beaten, shocked with electric stun guns, blindfolded and had their hands tied with plastic handcuffs. The armed men drove Ko Tee away in a car, leaving his wife and friend at the house.

Ko Tee was a former DJ at Red Guard Radio in Pathum Thani who became the leader of a hardcore Red Shirt faction that fought several violent battles against royalist protesters. He fled Thailand after he was accused of lèse majesté over comments made in a VICE News documentary in 2014.

According to a military source with direct knowledge of the operation, the men who kidnapped him were Thai special forces soldiers. They drove him to a remote area of forest where they tortured him, murdered him, urinated on his corpse, and buried him.

The next person to disappear was a rising star in the Thai military.

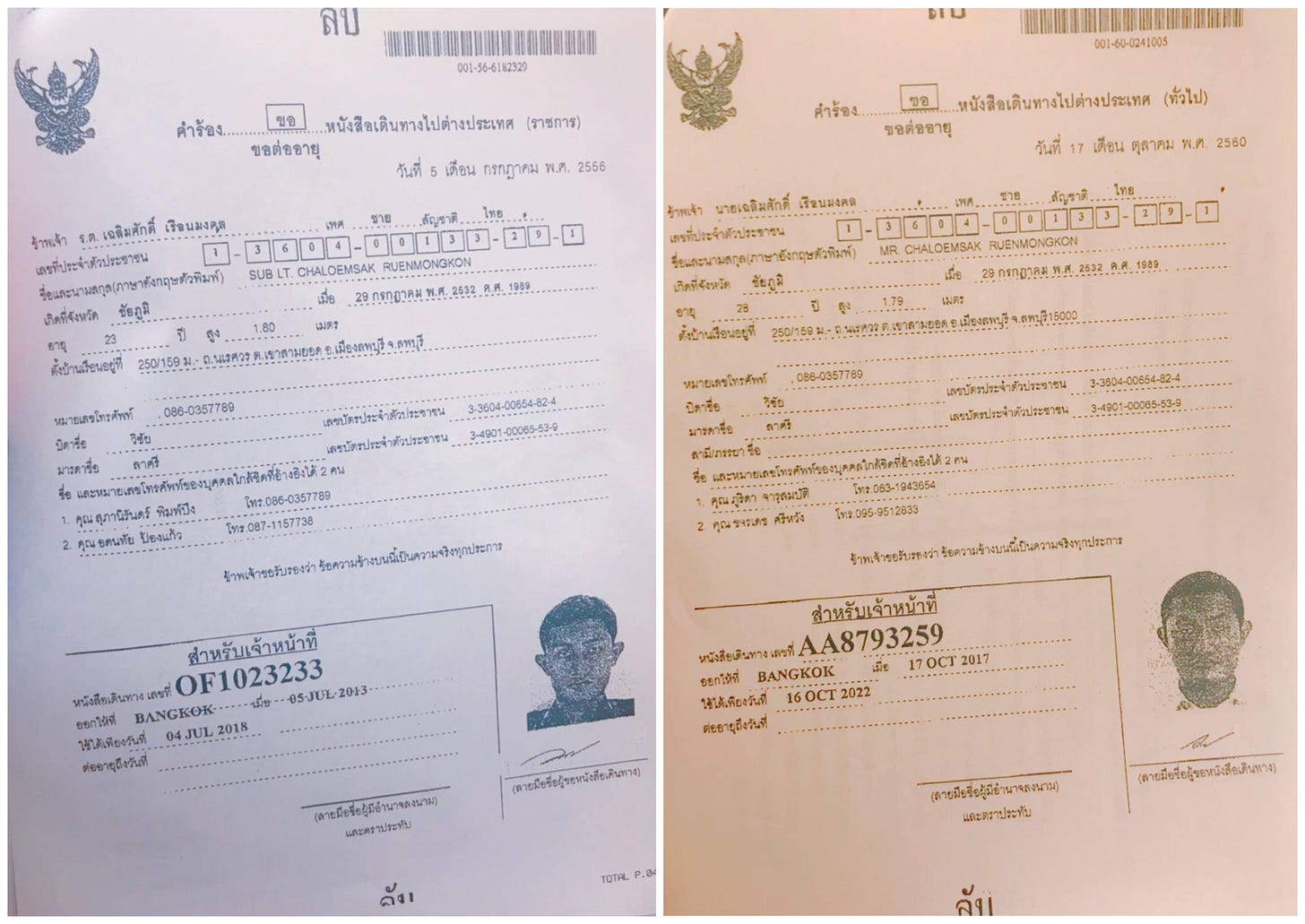

Chaloemsak Ruenmongkon was a sub-lieutenant in the elite “red beret” special forces based in Lopburi, regarded as one of the best and brightest of his generation. He was personally mentored by commander-in-chief Chalermchai Sitthisart. He was in a special battalion of the 3rd Special Forces Regiment, which is designated as part of the King's Guard. His unit focused on special warfare and black ops.

Chaloemsak had concluded the Thai monarchy was toxic, and was building a network of progressive young officers who wanted democracy.

On March 30, 2018, while he was in Narathiwat, Chaloemsak was summoned back to Bangkok because he was suspected of being behind the anti-monarchy and anti-junta Facebook page “พิซซ่าชาวใน”. He contacted Chalermchai, asking for reassurances about his safety, but Chalermchai said the case was so serious he could offer no help or protection.

On March 31, Chaloemsak was interrogated in Bangkok by a colonel working in military intelligence. On April 1, he was told by an aide de camp that the findings of the investigation had been sent to King Vajiralongkorn's team in Germany. He was told Vajiralongkorn was personally aware of his case, and that he faced severe punishment. So he decided to try to escape.

Chaloemsak flew to Phnom Penh, where he planned to seek protection from the UNHCR. But they refused to help him. While in Cambodia he discovered his Thai bank accounts had already been shut down. He knew Cambodia was not safe, so he flew to Manila in the Philippines, where he arrived on April 6, 2018.

Meanwhile, the Thai authorities cancelled his civilian and military passports. Here are the documents, which were leaked to me by Thai sources.

Chaloemsak checked in to a backpacker hostel in Manila, and planned to visit the UNHCR when it reopened after the weekend. He made contact with the UNHCR office and received a response.

But Chaloemsak Ruenmongkon never arrived at the UNHCR offices in Manila, and his family and friends have never heard from him again.

Trusted sources have told me that Chaloemsak was captured in Malaysia, taken back to Thailand, and then disappeared. I have no explanation for how he ended up in Malaysia after he was so close to safety in Manila, but during his escape he remained convinced that his comrades in the Thai special forces would help him. It’s probable that he was betrayed by a friend who asked him to come to the Thai-Malaysian border, where Thai special forces are active, and then handed him over to the regime.

Next, more dissidents went missing from Laos, and this time the team sent to murder them bungled the disposal of their bodies.

In December 2018, Surachai Danwattananusorn and his comrades Chatchan “Phoo Chana” Boonphawal and Kraidej “Kasalong” Luelert vanished from their house in Vientiane.

Surachai was a veteran activist who was sentenced to death after the Thammasat University massacre in 1976 due to his membership of the communist movement, but was pardoned in 1988. In 2012 he was sentenced to seven and a half years in prison for lèse majesté, and he was released in October 2013 after another royal pardon.

Following the 2014 coup, he escaped to Laos with Chatchan and Kraidej. The three men were last seen alive on December 11, 2018. Friends who visited after that date found their house deserted.

Later that month, on December 26, 27 and 29, three corpses washed up on the banks of the Thai side of the Mekong River. The bodies were wrapped in rice sacks and fish nets, tied with rope. One of the corpses disappeared after police and a naval patrol boat arrived at the scene. The two other bodies were sent to the Forensic Science Institute in Bangkok and identified as Chatchan and Kraidej.

Their legs had been broken, probably as a result of torture, they were handcuffed, and they had been disembowelled and stuffed with concrete.

Meanwhile, the Thai regime was demonstrating its willingness to deny a safe haven to people fleeing authoritarian countries elsewhere, to help build reciprocal arrangements that would help them hunt down Thai dissidents abroad.

The most notorious case was the forcible deportation of 109 male Uyghur refugees in July 2015 to Chinese security officers who had arrived in Bangkok on a special chartered flight. The Chinese treated the Uyghurs like violent terrorists, restraining their hands behind their backs, placing black hoods over their heads, and affixing a piece of paper numbering each refugee with bright red numerals to the front of their t-shirts.

Two Chinese security agents in matching blue uniforms and caps and white face masks were assigned to each detainee. They dragged them, hooded and restrained, back onto the China Southern Airlines charter plane, and sat on either side of each prisoner for the flight.

Chinese television broadcast images of the extraordinary scenes of extraterritorial human rights violations taking place on Thai soil. The fate of the deported men is unknown, but China’s appalling human rights record in Xinjiang has been widely reported.

The mass deportation led directly to the bombing of the Erawan Shrine on August 17, 2015. A pipe bomb containing three kilograms of TNT and hidden in a backpack left under a bench killed 20 people and wounded 163, with most of the casualties foreign tourists who were visiting the shrine.

Meanwhile, the Thai regime was also sending back dissidents from Cambodia, to try to build a relationship with Hun Sen that would allow them to target the exiled Thai activists in Phnom Penh.

During 2018, two Cambodian activists who had traveled to Thailand to seek refugee status were forcibly repatriated. Labour rights activist Sam Sokha, who faced prosecution in Cambodia for throwing a shoe at a billboard of dictator Hun Sen during a protest, was detained in a Thai immigration facility in January 2018 and jailed in Cambodia in February after being deported.

Rath Rott Mony, a trade union leader and translator, was arrested in Thailand in December 2018 after a request from Cambodia which accused him of damaging the country’s image by working on a documentary on child prostitution. He was refused refugee status and sent back to Phnom Penh where he was jailed for two years.

In January 2019, Vietnamese journalist Truong Duy Nhat traveled to Thailand to seek political asylum in a third country. He visited the offices of the UNHCR on January 25 to apply for refugee status. The following day, he was seized by unknown men outside an ice cream store at the Future Park mall in Rangsit. He resurfaced two days later, in prison in Hanoi, and was subsequently sentenced to 10 years in jail. He told his lawyer that he had been arrested by Thai police and handed over to Vietnamese security agents who took him back overland to Hanoi via Laos.

By now it was clear that an “unholy alliance” of authoritarian Southeast Asian regimes was cooperating to hunt down dissidents seeking sanctuary and send them home — or worse, to turn a blind eye to their extraterritorial murder.

In May 2019, three more Thai dissidents disappeared — Chucheep Chiwasut and his comrades Siam Theerawut and Kritsana Thapthai.

They were leading members of a movement called the Organization for a Thai Federation, which advocated giving self-governance to the Isaan region of northeast Thailand, and had a logo with the red and white colours of the Thai flag but missing the blue, which symbolises the monarchy. Chucheep gained a wide following with regular YouTube videos in which he criticised the royals, using the pseudonym Uncle Sanam Luang.

The three men were arrested while trying to cross from Laos to Vietnam using fake Indonesian passports, but then vanished, with both Thailand and Vietnam claiming not to know anything about their whereabouts. They are also presumed dead.

Siam Theerawut’s mother Kanya continues to demand answers about what happened to her son, but she has never been given any information.

The case is particularly incriminating for the Thai regime because we know the three men were in Vietnamese custody and handed over to the Thais, even though deputy prime minister Prawit Wongsuwan has tried to deny this.

Vajiralongkorn’s efforts to crush dissent through fear, by oppressing dissidents in Thailand and ordering their kidnap and murder abroad, only made him even more unpopular and hated.

After the Constitutional Court — acting on direct orders from the palace — dissolved the progressive Future Forward Party in February 2020 and banned its leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit and other party executives from politics for 10 years, there was unprecedented criticism of the monarchy on social media, and “flash mob” protests were held at universities and schools across the kingdom.

Vajiralongkorn, who was living at the luxury Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl in Germany with a large harem of women, became increasingly enraged by the protests and escalating mockery of the monarchy.

He was incensed that palace insiders were leaking information to me about his lifestyle in Bavaria, and by the widespread disrespect towards him on social media. After Somsak Jeamteerasakul published a tweet in March 2020 with the hashtag #กษัตริย์มีไว้ทําไม — #WhyDoWeNeedAKing? — criticism of Vajiralongkorn went viral with more than 1.2 million tweets within 24 hours.

In May 2020, exiled dissident Junya Yimprasert launched a series of protests right outside Vajiralongkorn’s hotel in Bavaria, working with the German activist group PixelHELPER. Messages denouncing Vajiralongkorn and the military regime, and a notorious photograph of the king wearing a crop top, were projected onto the facade of the Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl.

Inside the hotel, according to one palace source, Vajiralongkorn’s anger “exploded like a bomb” at the audacity of protesters daring to denounce him right outside his Bavarian hideaway. Another source in the royal entourage says the king wanted to send his bodyguards out to assault the protesters, but was dissuaded by some of his more sensible advisers. Thai security guards drove out of the hotel twice in large black vehicles to intimidate the activists, but did not physically intervene.

Later in May, Vajiralongkorn’s fury deepened after the Facebook group Royalist Marketplace launched by exiled academic Pavin Chachavalpongpun quickly attracted hundreds of thousands of participants openly ridiculing the royal family.

Seething with rage, Vajiralongkorn decided the best way to respond was by murdering another exiled activist, believing this would terrify his opponents into giving up their struggle.

He ordered his security chief Jakrapob Bhuridej to find somebody to kill.

Jakrapob is the most brutal and feared member of Vajiralongkorn’s inner circle, responsible for overseeing the torture and beatings of palace staff who displease the king, as well as operations against democracy activists in Thailand and abroad. His family has become extremely influential thanks to Vajiralongkorn’s patronage, and his brother Jirabhop is chief of the Crime Suppression Division of the Royal Thai Police.

Thai embassies were told to try find out the home addresses of exiled dissidents, and Jakrapob's team began hunting for a target.

The Thai regime has been doing its best to monitor foreign-based critics for years, as a document leaked to me in 2017 shows. Wanchalearm is on the lower left of the document, and I am one of those on the top row.

But finding a Thai activist to kill was much harder by 2020 because almost everybody had left Cambodia and Laos, realising that they were not safe there.

During 2019, members of the activist folk band Faiyen, who had been stranded in Laos, managed to escape to seek asylum in France. As lead singer Romchalee “Yammy” Sombulrattanakul told AFP:

All the firebrand activists have gone, disappeared. We are the last targets.

After it had become clear that Cambodia was no longer a safe haven, most Thai activists who had sought sanctuary there also found a way out.

But Wanchalearm stayed. He knew Cambodia was getting much more dangerous, but he liked living there and was full of plans about businesses he could launch — every time I talked to him, he had a new idea for a project.

He had managed to get a Cambodian passport under the alias Sok Heng, was able to visit other countries several times, and could have successfully sought asylum somewhere safer, but he wanted to stay in Phnom Penh.

He had never been a vocal critic of the monarchy. His Facebook paged focused mainly on mocking the military regime rather than the royals. He wasn’t doing anything to openly provoke or challenge the palace.

But when Vajiralongkorn demanded another murder, his henchmen chose Wanchalearm as their victim because he was one of the few prominent exiled Thai dissidents still living in mainland Southeast Asia. He was the easiest target.

Most of the leading critics of the monarchy had been granted political asylum in countries with strong rule of law — Somsak in France, Pavin in Japan and Junya in Finland. Arranging a murder in one of these nations would be extremely difficult and politically dangerous. But killing somebody in Cambodia is easy to organise, and the palace knew that Hun Sen would turn a blind eye.

They also knew that killing Wanchalearm would send a message to all exiled Thai activists, because almost everybody knew him — and had been helped by him in their escape from Thailand.

On the evening of June 1, 2020, Thai Airways flight TG933 took off from Paris, heading for Bangkok. It was an unusual flight, because the struggling airline had cancelled almost all international routes two months earlier as a result of the pandemic, and TG933 was not one of the sporadic repatriation airlifts organised for Thais stranded abroad.

Officially it was a cargo flight, but the plane used, a Boeing 777 with registration HS-TKY, was not one of the airline’s usual cargo aircraft. It was the favourite Thai Airways plane of Vajiralongkorn and his top aides, usually used by them when they travelled between Europe and Thailand.

The flight manifest shows that four passengers were aboard — Jakrapob Bhuridej and three of his team. They landed at Suvarnabhumi early in the afternoon of June 2.

It was extremely rare for Jakrapob to leave Vajiralongkorn’s side, but he was going back to Bangkok for an important mission — overseeing the operation to kidnap and kill Wanchalearm.

Vajiralongkorn remained in Europe. On June 2 he flew from Munich to Zurich aboard one of his personal Boeing 737s, to visit his wife Queen Suthida.

Vajiralongkorn rarely spends time with Suthida when in Europe, preferring to live with his chief consort Sineenat “Koi” Wongvajirabhakdi and his harem at the Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl, while the queen lives a lonely life at Hotel Waldegg in the Swiss resort of Engelberg. But June 3 was Suthida’s 42nd birthday, which is probably why the king decided to go and see her.

On June 4, Wanchalearm was seized outside his apartment, in broad daylight. CCTV footage shows two security guards from the Mekong Gardens complex witnessing the abduction, and then the Toyota Highlander speeding off.

It’s likely that Wanchalearm was driven to a remote spot in Cambodia, tortured, and killed the same day. Notoriously, Vajiralongkorn enjoys watching video of his enemies being beaten and tormented, so Wanchalearm’s ordeal was probably filmed by the team that killed him, so the king could view it afterwards.

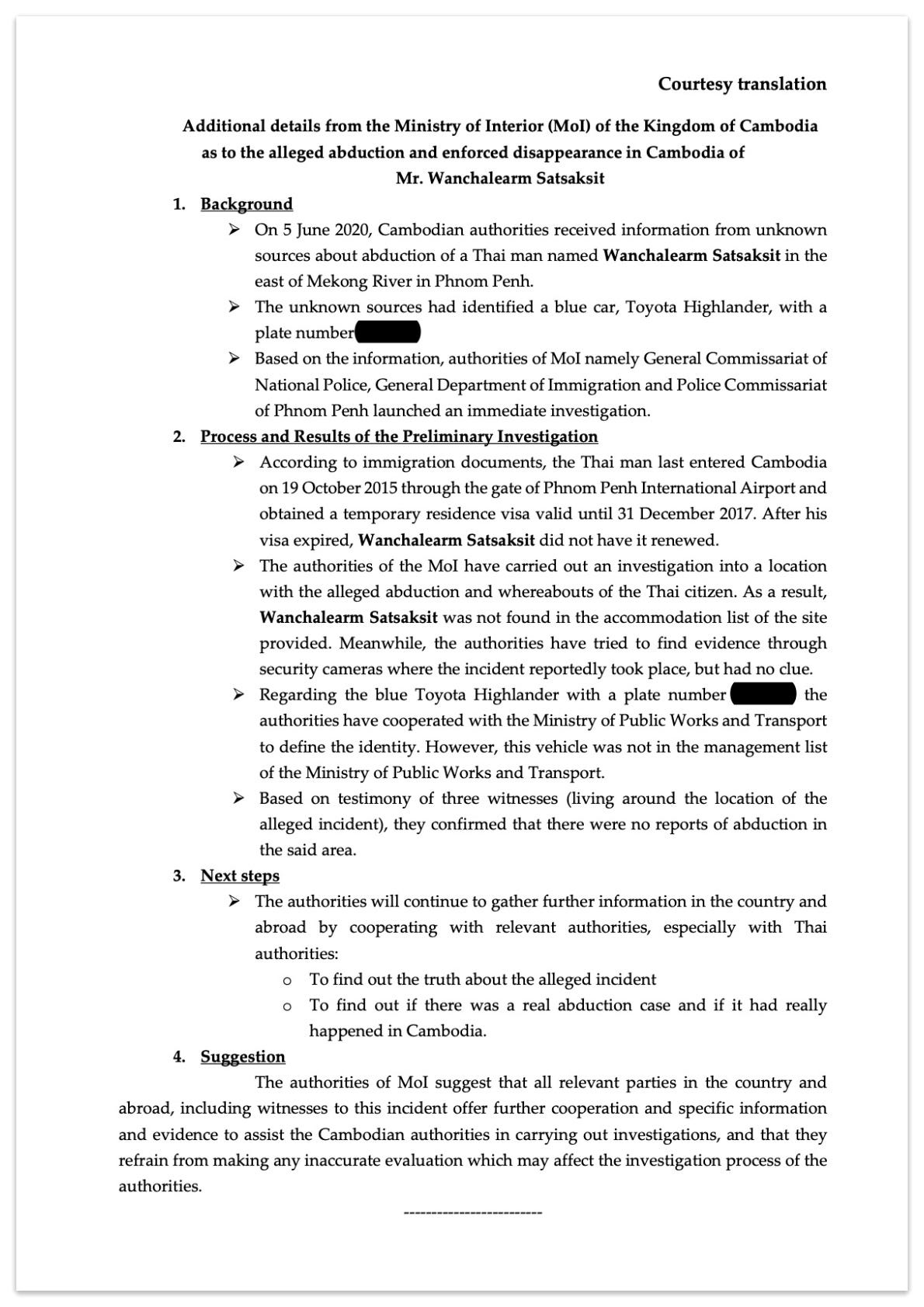

The authorities in Cambodia have never even bothered to pretend to investigate the incident. They continue to absurdly claim that they have not found any evidence a crime has been committed or that Wanchalearm was even in Cambodia.

Thai authorities say they have no jurisdiction and have also feigned complete ignorance about the case.

As Sunai Pasuk of Human Rights Watch says, the abduction and murder of Wanchalearm and other activists abroad was designed to create a climate of terror in which nobody dares speak out:

They want to maintain this ultimate fear that once you get in the way, the worst thing can happen to you and your family—that is, you are taken away for good, and no one knows if you still exist on this earth or not, then your family will suffer for the rest of their lives and beyond because they don’t know what happened to you.

He says the killings on foreign soil were also intended to send the message that: “No matter where you go, you can still be hunted down.”

But the murder of Wanchalearm Satsaksit was a disastrous strategic blunder by the Vajiralongkorn and his cronies. They thought it would put an end to mounting defiance of the monarchy. Instead, it poured fuel on the flames.

There was uproar in Thailand. #saveวันเฉลิม quickly became the top hashtag on Thai Twitter with more than half a million tweets after the kidnapping, and #ยกเลิก112 soon started trending too — a call to scrap the archaic lèse majesté law used by the palace for decades to try to stifle dissent.

Posters and street art with Wanchalearm’s face appeared all over Bangkok and beyond. The Student Union of Thailand organised a flash mob protest at the skywalk beside the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre the day after Wanchaleram’s abduction. Police tried to disperse the crowd, citing the need for social distancing during the pandemic, but the protesters refused to be intimidated.

Three days later dozens of people led by Somyot Prueksakasemsuk gathered outside the Cambodian embassy in Bangkok, demanding answers.

Rangsiman Rome, a democracy activist who had joined Thanathorn’s Future Forward movement and become an MP, raised the issue in parliament.

Reuters reported that Wanchalearm’s disappearance had “reignited protests against Thailand’s military-royalist elite”.

It galvanised and radicalised the democracy movement, and dragged the reputation of the Thai monarchy to its lowest point in history.

It was the moment when many younger Thais decided enough was enough, and became determined to confront the palace head on.

The killing was one of the main triggers for the extraordinary mass protests that shook the Thai regime in the second half of 2020, at which activists openly demanded fundamental reform of the monarchy.

Wanchalearm’s sister Sitanun, who he was talking to on the phone when he was abducted, has been campaigning tirelessly to demand the truth about what happened from the Thai and Cambodian authorities. Last November she flew to Phnom Penh with a legal team and presented a large dossier of evidence to a Cambodian judge.

She is determined to keep going:

I don’t have a future anymore, but if I don’t fight, if I don’t do this, let me ask you — who is going to do it? Because no one can tell our story as well as us, and no one can tell our story every day.

But Wanchalearm’s family and friends know that there is no prospect we will ever see him again. We know he is never coming back.

All we can do is try our best to find out the full story of what happened to Tar and the rest of Thailand’s disappeared, so that someday their killers may face consequences for what they have done.

Even I don’t know personally about Mr.Wanchalerm, but I can say with full confidently that he is a very good man who only has a good hope for others, even 1 years has passed

, but Kidnaping of him still shocking us thais who love and fighting for real democracy to be happen in this sad country….

We’re missing Not only him, but all dissenters who being forced disappear liked Ajarn Surachai Sedan and Uncle SanamLuang … Thai Monarchy and PM Prayuth Regime is nothing more than the head of Mafia Gangster who will make an offers cannot refuse to anyone who disobeyed them…sometime when go to bed, I can’t sleep properly because of imagine myself also being baged and force kidnaped by “them” at the night…This nightmare can happen to anyone who just disobeyed them, anyone who just said “no more!, to be the dust under their feet…

Finally, I would like to say “Thank you so much” to you again krub, Khun Andrew, for writing this above sad but very precious article…

😿❤️🌎👍

the sadistic, capricious, completely corrupt X's violent & carnal whims know no bounds...

this sh*t has to end-now!!!