The tragic history of refugees in Thailand

The military and palace are responsible for decades of atrocities and mistreatment of people seeking asylum, and the UNHCR lacks the courage to challenge them

Beyond the northwestern borders of Thailand, across the Salween River, is the land of the Karen people, the third largest ethnic group in Myanmar. For seven decades, Karen nationalist forces have fought an insurgency against the central government and military, hoping to win independence for their homeland, which they call Kawthoolei. After the Myanmar military seized power in a coup on February 1 the junta launched a murderous campaign to suppress dissent and intensified their attacks on ethnic forces. Last weekend, warplanes began airstrikes on Karen insurgent positions. More than 10,000 civilians fled their homes and around 3,000 crossed the river into Thailand seeking safety.

Prime minister Prayut Chan-ocha claimed Thailand was willing to accommodate refugees escaping violence in Myanmar, but it soon became clear the Thai military was pushing terrified Karen civilians back across the border. Reuters reported that Mae Sariang district chief Sangkhom Khadchiangsaen told a meeting:

All agencies should follow the policy of the National Security Council which is we need to block those that fled and maintain them along the border. The military has the main responsibility in managing the situation on the ground and we must not allow officials from UNHCR, NGOs or other international organisations to have direct contact and communication. This is absolutely forbidden.

Journalists trying to reach the area were turned away by Thai soldiers, but video evidence showed refugees being forced back across the river. Thai troops installed razor wire on the riverbank to deter further arrivals, and blocked efforts to deliver aid to stranded Karen villagers.

Prayut insisted the Karen had gone back to Myanmar without coercion because the situation was safe, telling reporters: “We shook their hands and wished them good luck as this is the humanitarian way.”

Foreign ministry spokesman Tanee Sangrat also lied about what had happened, denying there had been any forced repatriations, and sharing video footage of a few Karen who had been given medical treatment in Thailand to pretend the government has been providing major humanitarian assistance.

When I challenged him on Twitter he said the Thais had no obligation to give refugees any help at all, and touted the kingdom’s previous assistance for people fleeing Myanmar — around 80,000 people driven out of Karen and Karenni areas in the past two decades remain in Thailand.

The actions of the Thai regime over the past week have made it abundantly clear that they don’t want any more refugees arriving from Myanmar, however bad the situation becomes, and they intend to lie and conceal the fact they are sending desperate people back into a conflict zone.

Sadly this is nothing new. As this article explains, unfolding events on the Myanmar border follow a grimly familiar script.

“Scenes of the most appalling carnage”

Shortly before 7 pm on the evening of Monday, August 17, 2015, a pipe bomb containing three kilograms of TNT and hidden in a backpack was detonated at the famous Erawan Shrine at the Ratchaprasong intersection in central Bangkok. The shrine, dedicated to the Hindu creation god Brahma and built in 1956 to appease vengeful spirits apparently angered by construction work in the area, is one of Bangkok’s most popular sites for both Thais and foreigners to visit, and the area was crowded with locals and tourists. The blast scattered corpses and body parts across Ploenchit Road, and left maimed victims screaming in agony on the sidewalk.

Twenty people were killed and 163 wounded, with most of the casualties foreign tourists who were visiting the shrine. Reporting from the scene, BBC correspondent Jonathan Head described “scenes of the most appalling carnage”.

Prayut called it the “worst ever attack” on Thailand. But he has never admitted that the bombing was a direct result of one of the most egregious crimes against humanity his regime has been responsible for — the forcible repatriation of more than a hundred Uyghur refugees in violation of international law.

In March the previous year, 325 Uyghur men, women and children had been detained in two raids on people-smuggling camps in southern Thailand while they were trying to travel to a safe country after escaping the Xinjiang region of China. They were held at immigration detention centres in southern Thailand for more than a year, even though Turkey had offered to give them asylum. Eventually, on June 29, 2015, 173 women and children in the group were allowed to board a flight to safety in Turkey.

But on July 9, the Thais handed over 109 male Uyghur detainees to Chinese security officers who had arrived in Bangkok on a special chartered flight. The Chinese treated the Uyghurs like violent terrorists, restraining their hands behind their backs, placing black hoods over their heads, and affixing a piece of paper numbering each refugee with bright red numerals to the front of their t-shirts. Two Chinese security agents in matching blue uniforms and caps and white face masks were assigned to each detainee. They dragged them, hooded and restrained, back onto the China Southern Airlines charter plane, and sat on either side of each prisoner for the flight. Chinese television broadcast images of the extraordinary scenes of extraterritorial human rights violations taking place on Thai soil. The fate of the deported men is unknown, but China’s appalling human rights record in Xinjiang has been widely reported.

“We are shocked by this deportation of some 100 people and consider it a flagrant violation of international law,” said Volker Türk, UNHCR's Assistant High Commissioner for Protection. Facing international condemnation, Prayut said the deported men were not Thailand’s responsibility, even if they would face torture in China:

If we send them back and there is a problem that is not our fault.

In response to the deportation, protesters in Istanbul attacked the Thai honorary consulate, smashing windows and ransacking some parts of the building. Meanwhile, members of the underground Uyghur network in Thailand that funnelled refugees from Xinjiang to safety in Turkey via southeast Asia began plotting revenge. A month later, they planted the bomb at the Erawan shrine.

The police investigation was chaotic throughout. Two men, both Uyghur with Chinese nationality, have been arrested and charged with involvement in the bombing. Adem Karadag, also known as Bilal Mohammed, was detained at his apartment in the Pool Anant condominium complex in Nong Chok northeast of Bangkok, where police also found bomb making materials and fake Turkish passports. Yusufu Mieraili was arrested at the Cambodian border as he tried to flee the country.

The trial of Karadag and Mieraili began in 2016 and has continued at glacial pace for more than five years, with the Thai regime dragging its feet because it has no desire for the truth about what happened to be revealed. The Thai authorities have repeatedly claimed that the suspects are just members of a human trafficking mafia who planted the bomb because they were annoyed that their criminal activities had been disrupted by the police — a clearly ridiculous theory — because the regime refuses to acknowledge any link with its deportation of refugees to China.

But the Erawan Shrine bombing was just one in a long series of tragedies resulting from the inhumane treatment of refugees and asylum seekers by the Thai military over many decades.

“Like having a knife in our heart”

The attitude of successive Thai regimes towards refugees has been shaped by the nationalist ideology of the military and its chronic disregard for human rights, but also by the vast number of displaced people the kingdom has had to deal with.

Political upheaval in southeast Asia since the 1970s has driven successive waves of refugees into Thailand, totalling more than two million people over the decades. Few countries have ever had to cope with such a massive influx. Thai governments have long argued that the international community failed to do enough to help shoulder the burden.

In this environment, the military has usually chosen to do everything it can to reduce the number of refugees in Thailand, whatever the human cost. In particular, the military has repeatedly violated a fundamental principle of international law — the prohibition of refoulement, the forcible repatriation of refugees to countries where they are likely to face persecution. Time and again, Thailand has thrown out people seeking asylum, condemning them to oppression, imprisonment, torture, and in many cases, death.

Thailand never signed the two main international agreements on refugees — the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol — and the military has never regarded itself as having an obligation to give sanctuary to those seeking asylum.

After World War Two, the return of the French to their colonies in Indochina caused am influx of refugees, especially Vietnamese, to Thailand. They were treated harshly by the military regime of Field Marshal Phibun Songgram, confined to border provinces in the northeast and subject to arbitrary arrest. During the rule of Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat who seized power in 1951 they faced even worse oppression, and were frequently denounced them as spies, terrorists and communists.

In 1975, communist forces took power in Cambodia, Vietnam and then Laos. Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge on April 17, and the People's Army of Vietnam and the Viet Cong took Saigon less than two weeks later on April 30. Pathet Lao forces overran the last strongholds of the Hmong by the middle of the year and captured Vientiane in December. All of these developments caused hundreds of thousands of people to flee to Thailand in the years that followed.

Initially, the government was sympathetic towards Lao and Khmer refugees who were given the status of “displaced people” fleeing communist regimes. They were mostly housed in large refugee camps on the border, and although no effort was made to assimilate them and Thailand was reluctant to offer them a permanent home, they were allowed to stay.

But the Vietnamese continued to be treated with hostility by the military and police. Far-right royalists spread propaganda claiming the Vietnamese in Thailand were a subversive group plotting a communist takeover of the kingdom. In his birthday speech in December 1975, King Bhumibol Adulyadej declared:

Thailand is now a direct target of an enemy who wants to control our country. The enemy is directing its forces against us. This has developed to such a serious stage that it is a direct aggression against the country.

During 1976, the extreme right in Thailand encouraged worsening anti-Vietnamese hysteria as part of its efforts to bring down the democratically elected government. Vietnamese were accused of being foreign saboteurs intent on undermining Thailand. More than 16,000 were arrested and anti-Vietnamese hate groups violently attacked refugee settlements.

When far-right militias, police and soldiers massacred students in the Thammasat University campus on October 6, 1976, it followed days of rumours that “Vietnamese infiltrators” were among the young protesters. Extremist politician Samak Sundaravej, who during this period was close to the ultranationalist Queen Sirikit, was one of the main proponents of anti-Vietnamese conspiracy theories during the 1970s and played a key role in inciting the Thammasat massacre.

When boats full of Vietnamese refugees from the south of the country fleeing the communist regime began setting sail to seek sanctuary elsewhere in Southeast Asia, they found themselves unwanted everywhere. Malaysia and Indonesia were reluctant to accept refugee boats, and in Thailand, where anti-Vietnamese prejudice was at fever pitch, the Thai navy and police patrols turned back boats and prevented them from reaching shore. This image shows Thai police turning away a Vietnamese refugee boat in the Gulf of Thailand in November 1977.

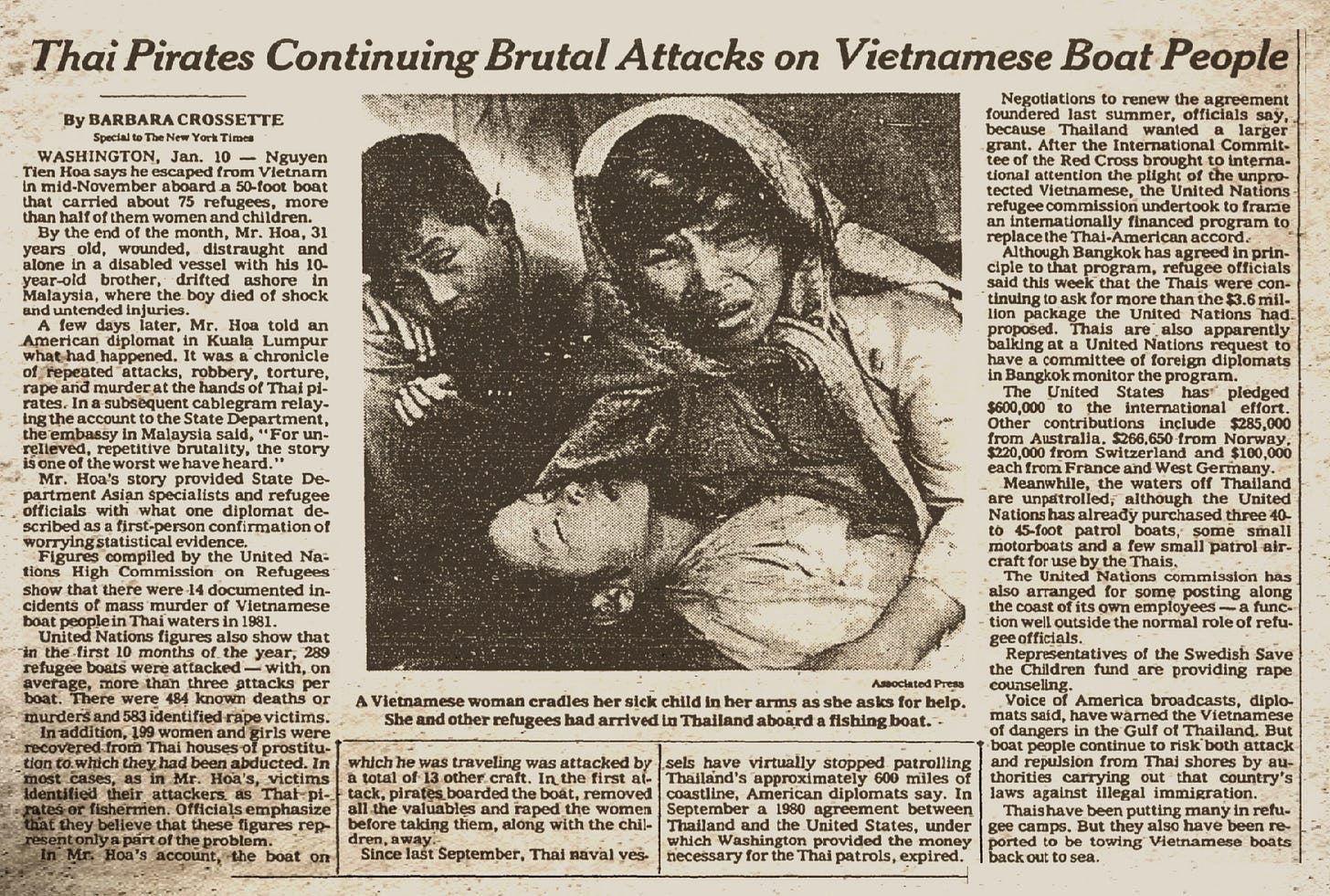

Vietnamese refugees faced a ghastly ordeal. As more boats packed with people fleeing the country began to set sail from southern Vietnam, many Thai fishermen turned to piracy, raiding and robbing refugee boats, kidnapping and raping women and girls aboard, and murdering any men who tried to stop them. Most refugee boats were targeted multiple times by pirates during their perilous journey west from Vietnam, and even once they were close to safety they were not allowed to come ashore.

The royalist regime installed by Bhumibol after the 1976 massacre was so extreme that in November 1977 the moderate army chief Kriengsak Chamanan seized power in a coup. Treatment of refugees improved, and the Thais began allowing Vietnamese boats to land.

But the sheer number of refugees arriving from Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam was becoming a serious problem, exploited by Kriangsak’s royalist enemies who argued it was unfair for Thailand to have to pay to feed and accommodate hundreds of thousands of foreigners who were a potential threat to national security.

After Vietnam invaded Cambodia in December 1978 to overthrow the Khmer Rouge regime, another huge wave of refugees began crossing the border. The numbers were becoming overwhelming, and under pressure from the new army chief Prem Tinsulanonda, who had been installed on the instructions of the palace, Kriangsak announced different rules for the latest refugees.

Instead of being classed as “displaced people” they were categorised as “illegal immigrants” who should be sent back across the border as soon as possible. They were herded into camps at the border under the control of the Thai military rather than the interior ministry. The UNHCR offered to help look after the refugees, but the Thais refused.

The army, under the command of Prem, began a policy of forcing refugees back over the border. In one of the biggest forced repatriations, 1,728 refugees in Aranyaprathet were loaded onto buses before dawn on April 12, 1979, by Thai soldiers who told them they were being taken to a more permanent camp in Trat province. Instead they were taken to the border and forced back into Cambodia at gunpoint. For most refugees, this was a death sentence — there was hardly any food on the Cambodian side of the border, and conflict was still raging between the Vietnamese and the Khmer Rouge.

A report by United Press International the following week described one of the many smaller refoulements that happened throughout this period — 12 refugees including eight women and children were forced back across the border “despite crying and hugging the feet of the soldiers”.

On April 16, as Thai soldiers tried to force another 37 refugees back to Cambodia, the UNHCR field officer in Aranyaprathet, an Australian called David Taylor, made a dramatic intervention to save them. As the Bangkok Post reported, he “hugged one of the children and dared the soldiers to shoot him if they wanted to push the group back”. This infuriated the Thai military, and Prem responded on April 19 by announcing the UNHCR was banned from any role looking after the new refugees, who would be forcibly returned to Cambodia. He declared:

If the refugees are sick, we will give them medical treatment. If they are hungry, we will feed them. And when they have recovered, they will be pushed back across the border.

The UNHCR office in Bangkok, led by a British official called Leslie Goodyear, had a policy of not trying to challenge the Thai regime. Although they issued a statement in support of Taylor, in fact they thought he had gone too far and soon removed him from his position.

The spineless behaviour of the UNHCR in Bangkok caused significant internal dissent, as journalist William Shawcross reported in the Washington Post:

At that time the official policy of the Bangkok office of the UNHCR was not to antagonize the Thais lest they treat the Cambodians even worse. Many junior UNHCR officials were strongly opposed to this seeming acquiescence in forcible repatriation. They felt it would only encourage the Thais, and they seem to have been right.

In early May, the UNHCR heard about another atrocity. On April 15 in Buriram province, 826 refugees were put into buses, driven to a remote part of the border, and forced to walk two and a half hours to a steep cliff overlooking Cambodia. According to a report by UNHCR official Ove Ullerup-Peterson: “The whole group was pushed over by Thai soldiers and killed.”

Over several days from June 8 onwards, around 45,000 refugees in Aranyaprathet and at temporary camps throughout eastern Thailand were forced onto buses by soldiers, and driven to a cliff edge overlooking Cambodia near Preah Vihear temple, a sacred site contested by both countries. The refugees were forced to climb down the precipitous slope through several minefields into Cambodian territory. Thai soldiers stole most of the valuables and possessions the refugees still had with them before forcing them down the cliff path. Anyone who resisted or refused to descend was shot. Hundreds were killed when landmines exploded, triggered by the refugees stumbling down the mountain.

Once the survivors reached the bottom of the cliffs, they found themselves trapped in a heavily mined wilderness, warned by Vietnamese soldiers that it was unsafe to advance further into Cambodia. A New York Times report on June 22 quoted the Cambodian government as saying 300 refugees had been shot dead by Thai soldiers or killed by mines during the exodus down the mountain path, and many more had died from illness.

In fact, the death toll was much higher, and continued to rise as the refugees remained stranded in no-man’s land at the bottom of the cliffs. They were starving, exhausted, terrified, and whenever they tried to move further into Cambodia they set off more landmines. In a confidential cable on June 27, US ambassador Morton Abramowitz wrote:

Those forced back have clearly undergone a harrowing experience. A very good source read me a short letter from one of the Thai troops who participated in the refoulement. He claimed to have seen 2,000 bodies as of June 12 with more than 500 killed by mines. Thai troops shot others: he wrote specifically about one such soldier, a Seua Luong (Yellow Tiger) who boasted of killing 12 and taking their gold and clothing. Other refugees, he noted, died from lack of food.

One refugee, 28-year-old Lim Sun Theng, said that a “group of repatriates climbed the hill and prayed on their knees to the Thai soldiers guarding the ridge”, only to be “beaten, kicked, or shot before being forced back down the slope”. He personally saw Thai soldiers murdering at least 13 refugees including a 10-year-old boy “shot and killed when he cried after receiving only two cups of rice from a soldier in exchange for 500 baht”. All the survivors of the atrocity had similar stories to tell.

A US embassy source who was able to visit the trapped refugees at the end of June reported that “fatalities from malnutrition, exposure, disease, and mine explosions may number 200 or more daily” and that “the dead lie unburied and the stench is overpowering”. He estimated most of those still alive were within a week of death.

On July 5, Ambramowitz shared the text of a message that one group of refugees had managed to pass to Thai farmers on the border.

To all the people in the world. Please urgent to help us. We are refugees from Cambodia that used to stay in Aranyaprathet. Now the Thai government has sent us to Preah Vihear from Sisaket province. This place is very dangerous, hard to walk. Our people and children cannot walk. They stay without food, water and medicine. It rains every day, we have no shelters, there are plenty of mines. Many of us have died. Now about 1,000 left, some seriously sick — no food, no water. During day time we cannot rest, during night time we cannot sleep. Rainy season is very tough. All night we have to stay without shelter under the rain.

Our children cry. When we hear the sound of their crying it is like having a knife in our heart.

We call on all the people in the world to pity us, send food and medicine.

We now have stay 10 days without food or water. Even if our bodies would be built with iron, we could not stay.

Thanks to all people for their help.

Meanwhile, the US ambassador pleaded with Kriangsak to allow some humanitarian aid, saying he “was deeply concerned at the potential disaster to the people as well as to the image and position of Thailand in the U.S. if the world learned that 5,000-10,000 Khmer repatriates starved to death on the border of Thailand”. Kriangsak replied that his options were limited because military hardliners were opposed to any assistance to the refugees:

He could not trust many people in his government on this. There were too many Thais, particularly military, opposed to any humanitarian approach to this problem. He felt that only a limited number of people could be relied on to carry out his instructions.

Eventually, during July, some of the refugees were able to find a way through the minefields into Cambodia with the help of Vietnamese soldiers. A couple of thousand were rescued with the assistance of the US embassy, and a few thousand more managed to find a way to escape back to Thailand, evading Thai soldiers. Several thousand died, though the exact number of those who were shot, blown up by mines, or starved to death will never be known.

Meanwhile, the military had resumed blocking Vietnamese boats. In a press release cabled from Geneva to Bangkok on June 29, 1979, the International Committee of the Red Cross said it was being prevented from providing any humanitarian relief to “more than 15,000 ‘boat people’ who are at sea and are refused permission to land” as well as “some 80,000 Cambodians who have sought refuge in Thailand and of whom over 40,000 have been forced back and are trapped without the basic means of survival”. It was also unable to help “the hundreds of thousands of victims of the conflict in Cambodia”. It called on all ships to follow the convention of aiding those in distress, and demanded that governments stop turning refugees away.

Facing international pressure, and probably also shocked by scenes he witnessed on a visit to the Cambodian border on October 18, 1979, Kriengsak changed Thailand’s policy, declaring the country would have an “open door” to refugees and stop turning people away or forcing them out. Right-wing nationalists were furious at the U-turn, and it contributed to Kriangsak being ousted in February 1980. He was summoned to visit Bhumibol in Chiang Mai with Prem, and told to resign. Bhumibol’s favourite general Prem Tinsulanonda became Thailand’s new prime minister, and the “open door” policy was ended for good. Instead, Prem began a strategy of so-called “humane deterrence” to try to keep refugees out, with those who managed to enter Thailand housed in grim conditions in spartan border camps to discourage others from following them.

Large numbers of boats were still setting sail from Vietnam. The peak of the exodus was in 1978 and 1979, but in the early 1980s hundreds of boats a year were still seeking refuge. By now the Gulf of Thailand was infested with Thai pirates preying on the refugees, and in September 1981 the Thai navy stopped patrolling the area, allowing refugees to be robbed and raped with impunity. Prem claimed Thailand could not afford to patrol its own coastal waters and would not resume unless the country received millions of dollars from the international community.

But while the navy did nothing to prevent refugees being targeted by pirates, Thai vessels still pushed many Vietnamese boats back to sea. Some boats were allowed to land, but often hardly anyone was left aboard, with the men murdered and the women and girls kidnapped, repeatedly raped, and left to die on lawless islands like Koh Kra or trafficked to brothels in Bangkok.

Thailand’s brutal policy of leaving refugees to the mercy of pirates had the desired effect — most boats stopped heading to Thailand.

“Hell is real”

During the 1980s, new waves of refugees crossed the border into Thailand. From 1984, Karen and Karenni refugees began arriving from Burma, fleeing the conflict between the military and ethnic insurgent groups. Another offensive by Vietnam in Cambodia in late 1984 and early 1985 pushed around 200,000 people into Thailand. Hundreds of thousands of lowland Lao also arrived and were housed in camps in Nong Khai along with the Hmong refugees who had entered Thailand the previous decade.

Prem’s government continued to do its best to send refugees back. During 1986 and 1987, thousands of Hmong and Khmer were forced back across the border. In 1987, Prem officially adopted the policy of pushing all Vietnamese refugee boats back out to sea. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people died as a result.

But while the regime did its best to remove as many refugees as possible, hundreds of thousands remained, probably close to half a million by the time Prem finally stepped down as prime minister in 1988, moving into a role where he continued to run Thailand behind the scenes on behalf of Bhumibol as de facto head of the privy council.

During the 1990s, the number of refugees at the borders with Laos and Cambodia finally began to decline substantially as some were resettled in other countries and others were forcibly repatriated or returned voluntarily. But as the Myanmar military intensified its war against Karen and Karenni insurgents, tens of thousands of people crossed Thailand’s northwestern frontier and were settled at nine camps on the border. Instability in Myanmar became the source of most of the refugees arriving in Thailand, and the number rose well above 100,000 by the end of the decade.

In the 21st century, worsening persecution of the Rohingya minority in western Myanmar caused an increasing number to seek to flee by boat, particularly after 2005 when Bangladesh tightened border security and it became harder to enter Saudi Arabia by air, which was previously the favoured escape route of those fleeing the region.

Between 2006 and 2008 Thailand’s policy was to forcibly repatriate Rohingya who arrived by boat by sending them across the land border with Myanmar at Mae Sot or Ranong. They were left stranded far from home back in the country they had been trying to escape, and many were sentenced to years of forced labour in jail in Myanmar.

With the number of boats rising, Samak Sundaravej, who had risen to become prime minister, declared in April 2008 that he would maroon Rohingya refugees on a desert island. The man who had stirred up so much anti-Vietnamese hate three decades before was now targeting a new set of refugees.

In December 2008 the Thai military began using the island Ko Sai Deang as a holding centre for Rohingya boats which were then towed back out to sea. The ISOC officer put in charge of the Rohingya security operation, Colonel Manas Kongpan, was a notorious soldier who had been involved in the massacre of Muslims at the Krue Se mosque in Pattani province in April 2004. Manas was also a key figure in a criminal network generating funds for Thailand’s crown prince, Vajiralongkorn, and run by Pongpat Chayaphan, head of the police Central Investigation Bureau and uncle of Vajiralongkorn’s third wife Srirasmi.

During 2009 the Thai military dragged several Rohingya boats back to sea, sometimes after disabling their engine. At least 300 people drowned trying to swim to shore from marooned boats while suffering from malnutrition and dehydration.

From June 2012, increasing violence against the Rohingya caused a new surge in refugees trying to escape by boat. Unlike previous waves of Rohingya refugees which were usually working age men, now women, children and elderly people were fleeing too. The Thais continued their policy of dragging refugee boats back out to sea.

In 2013, Thai navy personnel opened fire on Rohingya on Surin Island, killing at least two, witness told Human Rights Watch. In May 2015, the BBC managed to find a boat with around 350 desperate refugees aboard that had been towed away from Thailand by the navy. Those on board said at least 10 people had died and others had resorted to drinking urine. The boat finally reached safety in Indonesia.

In a grim echo of the fate of so many Vietnamese boat people in previous decades, the Rohingya were not just pushed back to sea by the Thai navy, but they were also targeted by pirates, organised criminals, human traffickers and extortion gangs, who were usually in cahoots with Thai military officers and government officials.

Rohingya were captured and tortured in an effort to extort money from their relatives. Many were sold into slavery in plantations or fishing boats once all possible funds had been extorted, or murdered and buried in shallow graves. As Niran Pitakwatchara of the National Human Rights Commission commented: “Hell is real for the Rohingyas in Thailand.”

Vajiralongkorn divorced Srirasmi in late 2014 and began a purge of her relatives and the criminal network they had run. Manas Kongpan, who by now had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant general, was caught up in the purge. He was arrested in June 2015 and sentenced in 2017 to 27 years in jail for human trafficking, increased to 82 years in 2019.

Several powerful officials and businessmen in southern Thailand also received long sentences, but the network’s connection to Vajiralongkorn was never exposed, and a senior policeman investigating the case, Major General Paween Pongsirin, fled to Australia in December 2015 to claim political asylum after being ordered by the palace to keep quiet about what he had discovered.

The agony of the Rohingya worsened in 2017 when the Myanmar military launched a genocidal campaign to drive them out of the country. Villages were torched, and thousands of people were murdered and raped. Most of the refugees fled overland to Bangladesh, with a quarter of a million forced into exile over the border, but there was a renewed surge of boats too. Thailand maintained its policy of refusing to allow the refugees to come near its shores.

By 2020, when countries closed their borders because of the coronavirus pandemic, the plight of the Rohingya was more hopeless than ever.

"Thailand is a land of smiles. We will not send anyone to die."

When the military junta led by Prayut and Prawit Wongsuwan seized power in a coup in 2014, it heralded a grim new chapter for the safety of refugees in Thailand.

Scores of Thais fled the country in the aftermath of the coup, some seeking a safe haven in Laos and many more escaping via Cambodia to asylum in Europe, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. Refusing to recognise the right of Thais to receive asylum abroad to escape persecution at home, the junta tried to pressure Western countries to allow the extradition of Thai exiles. None of them complied.

The regime struck sinister secret deals with other authoritarian countries in the region and beyond. The junta would agree to send back dissidents and refugees seeking sanctuary in Thailand, even if they would face persecution and imprisonment, and in return other oppressive regimes were asked to allow murder squads organised by the palace to kidnap and kill Thai dissidents on foreign soil.

Over the past decade, the absolute monarchy that rules Bahrain has cracked down brutally on dissent following a popular uprising in 2011 demanding democracy. The regime is notorious for torturing and jailing anyone suspected of joining protests against the monarchy. The royal families of Bahrain and Thailand have a close relationship, and also strong business ties — they jointly own Kempinski Hotels Group, and also the Siam Kempinski Hotel in Bangkok which is built on land owned by Princess Sirindhorn. In December 2014, Thailand forcibly repatriated a 21-year-old Bahraini despite clear evidence he would face severe persecution.

Ali Haroon was arrested in Bahrain in 2013, and human rights organisations say regime security forces tortured him in detention — “beating him, forcing him to stand in stress positions, stepping on him, and depriving him of food, water, and sleep until he signed a coerced confession”. He was jailed for life for his alleged role in the democracy movement but managed to escape from prison in May 2014 and fled to Turkey, then Hong Kong, and then Thailand, which he entered with a valid visa. On December 13, he tried to board a plane to Baghdad at Suvarnabhumi Airport, hoping to later travel to Europe to claim asylum.

But by this stage, the Bahraini regime had asked Interpol to issue an international Red Notice for Haroon’s arrest, and he was detained by the Thai authorities. The UNHCR notified Thailand that Haroon would face torture and human rights violations if he was returned to Bahrain, but the junta ignored this.

Five days after his arrest, Haroon was handed over at Suvarnabhumi to Bahraini police officers who beat him, sedated him, shackled him and loaded him onto a Gulf Air plane to Manama in a wheelchair. He was so badly injured during his rendition that he had to be hospitalised on arrival in Bahrain. He was returned to jail, and has told family members that he has been regularly tortured.

In July 2015, Thailand deported the 109 Uyghurs, leading to the Erawan Shrine blast the following month, but the attack didn’t stop the regime sending back people seeking safety on Thai soil. At least three more people were unlawfully returned to China later that same year.

The first was Gui Minhai, a prolific Chinese author with Swedish citizenship who was one of the founders of a publishing company that owned the Causeway Bay Books store in Hong Kong. Gui, who was writing a book on the love life of Chinese president Xi Jinping, vanished from his apartment in Pattaya after an unknown man arrived at the condominium on October 17. He resurfaced in China three months later, making an apparently coerced confession to past crimes. Thailand did nothing to investigate his kidnapping and enforced return to China. Four other people linked to Causeway Bay Books were detained by Chinese police in Hong Kong and Shenzen.

In November 2015, two Chinese activists who had already been granted refugee status by the UNHCR were sent back in another violation of international law. Cartoonist and blogger Jiang Yefei, who had been living in Thailand since 2008, and former police officer Dong Guangping, who had arrived in September 2015, were arrested in Bangkok on October 28 and charged with immigration offences.

Both men had previously spent time in jail in China because of their political activities. Canada offered to grant asylum to the men and their families but on November 12, Jiang and Dong disappeared from their cell at the immigration detention centre at Suan Phlu and never returned. They were returned to China against their will, forced to make a televised confession to crimes they did not commit, and jailed.

Prayut claimed that the Thai authorities didn't realise that the men were under the protection of the UNHCR and had been offered asylum in Canada. He told reporters:

They violated immigration law and after checking we found that there was an arrest warrant from the source country. We were asked to send them back and we had to send them according to procedure. What was said about protection from UNHCR — we did not know about that.

We told the source country that if they take them they have to look after them and not violate human rights and they gave their word.

A document seen by Reuters showed that Prayut was lying — the UNHCR had informed Thai authorities that the men were refugees awaiting resettlement in Canada.

In May 2017, Thai officials allowed Turkish security agents to force Muhammet Furkan Sökmen onto a plane to Istanbul despite warnings that he faced political persecution if he was sent back.

During 2018, two Cambodian activists who had traveled to Thailand to seek refugee status were forcibly repatriated.

Labour rights activist Sam Sokha, who faced prosecution in Cambodia for throwing a shoe at a billboard of dictator Hun Sen during a protest, was detained in a Thai immigration facility in January 2018 and jailed in Cambodia in February after being deported.

Rath Rott Mony, a trade union leader and translator, was arrested in Thailand in December 2018 after a request from Cambodia which accused him of damaging the country’s image by working on a documentary on child prostitution. He was refused refugee status and sent back to Phnom Penh where he was jailed for two years.

Another refugee arrested in 2018 was Bahraini footballer Hakeem al-Araibi, who eventually managed to evade attempts by the Bahrain monarchy and their Thai allies to send him back thanks to a campaign by Australian sports stars and celebrities.

Araibi had been detained and tortured in Bahrain in 2012, accused of being part of a crowd that had attacked a police station with Molotov cocktails even though he’d actually been playing in a nationally televised football match at the time. He was released on bail after 45 days in detention, and when he was part of the Bahraini national team for a match in Qatar in 2013 he took the opportunity to escape. He travelled through several countries and managed to reach Australia, where he applied for asylum and tried to earn a living as a football player.

In 2017, he married his wife, also from Bahrain, and was granted political asylum. It seemed like he was finally safe, so a year later, he took his wife on a holiday to Thailand as a belated honeymoon.

But the Bahraini regime had not forgotten about him. They had been tracking his movements, and when they learned he was planning to go to Thailand they asked Interpol to issue a Red Notice and told Thai authorities to arrest him on arrival. The Interpol arrest warrant should not have been issued, because Araibi had already been granted asylum by Australia and it’s illegal for countries to request a Red Notice for refugees who have fled for political reasons.

When Araibi and his wife arrived at Suvarnabhumi on November 27, 2018, Thai police were waiting for him. He was arrested, sent to the immigration detention centre at Suan Phlu, and then to Bangkok Remand Prison where he shared a cell with 40 people.

According to international law, Araibi should never have been detained. As a refugee granted asylum in Australia it was illegal to send him back to Bahrain. But because of their cosy relationship with the Bahraini monarchy, the Thai regime ignored the rules and kept him locked up, even after Interpol rescinded the Red Notice.

After intense lobbying by Australian prime minister Scott Morrison, and campaigning by retired Australian football captain Craig Foster and many other sporting figures and celebrities, Thailand finally agreed to let Hakeem go free in February 2019. Thai foreign minister Don Pramudwinai flew to Manama to personally apologise to Bahrain’s royals.

While Arabi was in jail in Thailand, another refugee from the Middle East also narrowly escaped being sent back into danger. Rahaf Mohammed al-Qunun, an 18-year-old Saudi woman, arrived at Suvarnabhumi on January 5, 2019, en route to Australia where she planned to claim asylum, after fleeing from her abusive family during a holiday in Kuwait. Her relatives had alerted the Saudi authorities that she had tried to escape, and the Thai regime allowed Saudi officials to intercept her in transit it Bangkok and confiscate her passport, making it impossible for her to continue her journey to Australia. She was sent to the Miracle Transit Hotel at the airport to await deportation back to Kuwait.

But she still had her phone, and from her hotel room she began sending tweets in Arabic explaining her plight and asking for help. She only had 24 followers, and the situation seemed hopeless, but her tweets saying she feared being killed if she was sent back to her family started getting noticed, and within hours the hashtag #SaveRahaf was trending worldwide. As Thai and Saudi officials arrived at the hotel to deport her, she barricaded herself inside her room and kept on tweeting. Soon she had more than 50,000 followers and the situation had become so embarrassing for Thailand that the government had to promise not to forcibly repatriate her.

Immigration police chief Surachate Hakparn told reporters: “Thailand is a land of smiles. We will not send anyone to die.” This was, of course, a blatant lie — Thailand has sent tens of thousands of asylum seekers to die since the 1970s.

But Rahaf was safe, and eventually flew to Canada which offered her political asylum. Saudi charge d’affaires Abdullah al-Shuaibi ruefully told Thai officials: “She opened a Twitter account and her followers grew to 45000 within one day. It would have been better if they confiscated her cell phone instead of her passport because Twitter changed everything.”

Also in January 2019, Vietnamese journalist Truong Duy Nhat traveled to Thailand to seek political asylum in a third country. He visited the offices of the UNHCR on January 25 to apply for refugee status. The following day, he was seized by unknown men outside an ice cream store at the Future Park mall in Rangsit. He resurfaced two days later, in jail in Hanoi, and was subsequently sentenced to 10 years in jail. He told his lawyer that he had been arrested by Thai police and handed over to Vietnamese security agents who took him back overland to Hanoi via Laos.

Meanwhile, as the Thai regime was allowing other authoritarian regimes to forcibly repatriate asylum seekers from its soil, it was hunting down and killing Thai dissidents elsewhere in southeast Asia.

Ittipon Sukpaen, known as DJ Sunho, disappeared in Laos in June 2016, and nothing has been heard from him ever since.

In July 2017, 10 armed men dressed in black, wearing black balaclavas, and speaking Thai, seized dissident Wuthipong Kachathamakul, also known as Ko Tee, at his house in Vientiane where he had been living in exile. Ko Tee, his wife, and a friend who was also in the house were beaten, shocked with electric stun guns, and were blindfolded and had their hands tied with plastic handcuffs. The armed men drove Ko Tee away in a car, leaving his wife and friend at the house. According to a military source with direct knowledge of the operation, the men who kidnapped him were Thai soldiers. They drove him to a remote area of forest where they murdered him, urinated on his corpse, and buried him.

In April 2018, Chaloemsak Ruenmongkon, an officer in the elite “red beret” special forces who had secretly run an anti-monarchy Facebook page, went missing in Manila while on the run from the Thai authorities.

In December 2018, Surachai Danwattananusorn and his comrades Chatcharn Buppawan and Kraidej Luelert vanished from the house where they had been living in exile in Vientiane. Later that month, on December 26, 27 and 29, three corpses washed up on the banks of the Thai side of the Mekong River. The corpses were wrapped in rice sacks and fish nets, tied with rope. One of the corpses disappeared after police and a naval patrol boat arrived at the scene. The two other corpses were sent to the Forensic Science Institute in Bangkok and identified as Chatcharn and Kraidej. Their legs had been broken, probably as a result of torture, they were handcuffed, and they had been disembowelled and stuffed with concrete.

In May 2019, three more dissidents — Chucheep Chiwasut, who was known as Uncle Sanam Luang, and his comrades Siam Theerawut and Kritsana Thapthai, also disappeared. They were arrested while trying to cross from Laos to Vietnam using fake passports, but then vanished, with both Thailand and Vietnam claiming not to know anything about their whereabouts.

On June 4 last year, Wanchalearm Satsaksit, a 37-year-old Thai activist living in exile in Cambodia, left his Phnom Penh apartment to buy meatballs at a roadside stall, while chatting on his mobile phone to his sister Sitanun in Thailand. Suddenly a black SUV pulled up and several armed men jumped out, grabbing Wanchalearm before driving away. Over the phone, his sister heard him repeatedly shouting: “I can’t breathe.” For thirty minutes she stayed on the call, listening to muffled noises, before the line went dead. Wanchalearm has never been seen again.

Sources in the palace say the abductions and killings were masterminded by Vajiralongkorn’s security chief Jakrapob Bhuridej and carried out by a special unit of soldiers and police in the Royal Guard 904. By allowing foreign governments to repatriate asylum seekers in Thailand, the regime won their acquiescence to murder its own citizens abroad. Never before in modern Thai history has the country been ruled by a government that so blatantly and systematically violates international law.

“Not my fight”

Throughout several decades of mistreatment of refugees by successive Thai regimes, the response of the UNHCR office in Bangkok has been consistently useless.

Several UNHCR officials have done their best to make a difference, and some have been heroic — like David Taylor, who fought to save Cambodian refugees in Aranyaprathet in defiance of the Thai military. But most of them have been more like his feckless boss Leslie Goodyear, unwilling to make a stand.

The dismal record of the UNHCR in Thailand speaks for itself — they have consistently failed to stop successive regimes mistreating and forcibly repatriating refugees.

They have also at times taken overtly political positions in support of the royalist establishment in Thailand. After the death of King Bhumibol Adulyadej on October 13, 2016, ultraroyalists launched an aggressive campaign of online intimidation and death threats against activist Aum Neko, a refugee seeking political asylum in Paris, after she criticised the late monarch in a social media post. She was so afraid for her safety that she had to go into hiding in France. Some royalists incorrectly believed the UNHCR was helping her seek asylum abroad and flooded its Facebook page with angry comments. In response, UNHCR Bangkok issued an extraordinary statement:

The UNHCR Representation in Thailand has been made aware of entirely inappropriate comments made by an individual who claims to have sought asylum in France.

UNHCR states clearly and unequivocally that it has no direct or indirect connection to such an individual.

Asylum claims in France are determined solely by the French Government. UNHCR strongly condemns any comments attributed to this individual, which reportedly relate to the demise of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej.

UNHCR joins with the entire UN Community in reiterating its heartfelt condolences at the passing of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej, whose legacy of good works, devotion to duty and compassion for people stands now and in the future as a model not just for Thailand but for the world.

The statement violated the UNHCR’s own rules about taking explicitly partisan political positions, and openly attacked an asylum seeker. UNHCR leadership in Bangkok seemed more interested in placating ultraroyalists than supporting refugees.

The organisation has become popular among royalist Thai celebrities who want to boost their reputation by performatively supporting the UNHCR.

In 2017, Thai-Swedish model Praya Lundberg was named the first UNHCR “goodwill ambassador” in Thailand. She has frequently been photographed with refugees at the Myanmar border and around the world, and has regularly featured in UNHCR promotional materials in Thailand.

In August 2017, Praya had a high-profile meeting with Prayut at Government House, describing it as “a true honour” and expressing “huge gratitude to the Prime Minister and the Royal Thai Government for generously hosting refugees over three decades”. It was shameless promotion of Prayut and the Thai regime that ignored the appalling record of the military in atrocities against refugees and the prime minister’s sinister deals with other authoritarian regimes to repatriate or murder dissidents. The meeting came just a month after the abduction and murder of Ko Tee in Laos. With Praya publicly praising Prayut, the UNHCR was left with even less leverage to try to persuade the regime to treat refugees better.

Other prominent royalists who have promoted their work with UNHCR Thailand include actress Sinjai “Nok” Plengpanich, a staunch supporter of the extremist PDRC movement that helped bring down Thailand’s democratically elected government in 2013 and 2014, singer Jennifer Kim, and actor Sunny Suwanmethanont who has been critical of pro-democracy protesters .

Following the disappearance of Wanchalearm Satsaksit in Phnom Penh in June 2020, the UNHCR declined to comment, and Praya also said she had nothing to say. In comments on Instagram she said it was a “highly political” issue and “not my fight”. She did not explain how her open support of Prayut aligned with her claims of staying out of politics.

Her comments were widely derided. As Pravit Rojanaphruk wrote in an open letter to Praya:

People are not asking you to take sides with a political dissident like Wanchalearm but people want you to stand for those who seek political refuge regardless of their political belief. It is here where you have failed and either failed or refused to recognize that many refugees are victims of political conflict and persecution.

If we do not acknowledge and confront this reality, it would be impossible to speak about and assist millions of refugees who fled political persecution, be it the Rohingya people who fled Myanmar to Thailand or Bangladesh, those who fled war in Syria and more.

But the UNHCR appears to have learned few lessons from the incident. Just last week, Chanoknan Ruamsap, a Thai activist who was given political asylum in South Korea after being accused of lèse majesté for sharing a BBC article on Vajiralongkorn, revealed that she had been suddenly dropped from a film about refugees being produced by the UNHCR in Korea. The organisation was afraid of offending Thai royalists.

A common theme in many accounts by refugees seeking sanctuary in Thailand is that they were routinely helped by ordinary people.

Eap Seav Keng, a 30-year-old Cambodian woman, was one of the refugees forced down the heavily mined cliffs near Preah Vihear by Thai soldiers. Desperately seeking safety, she trekked through a “valley where decaying human remains filled the air with a nauseating stench” with “corpses everywhere — women, children and men”. Her husband left the group to try to find food and never returned. After about 20 days wandering through the wilderness with little water and no food, she was “too weak to stand up or walk”. Her four-year-old son and three other relatives were also unable to walk. They tried to crawl onwards, hoping to find sanctuary somewhere.

After a short time, the three relatives gave up, but she continued crawling along the path, dragging her four-year-old son along on his back until that evening. She finally reached a rice field where sympathetic farmers helped her to Ban Saron village and gave her food, water and medicine. Two days later, when she could walk, she was brought to a temple where she stayed two more days until she and her son were brought to a temporary camp where they are awaiting transportation to the UNHCR-supported camp in Prasat, Surin province.

La Kieu Ly, a 16-year-old Vietnamese girl at Ban Thad refugee camp, told British journalist Jon Swain about her horrifying ordeal on a 24-foot with 20 others aboard that left the village of An Giang in May 1988, heading for Thailand. She was the only survivor.

A few hours out of An Giang on May 10, her boat met a Vietnamese fishing vessel, which confiscated the refugees’ money and gold in return for allowing them to proceed. Thirty-six hours later they met a Thai fishing boat, which threw them canned fish and sweets. But a few hours afterwards they were attacked.

Thai pirates rammed the boat twice until it sank. They plucked six girls, including Ly and her aunt and Kim, out of the sea but drove off the Vietnamese men with knives. The men drowned.

Then the terror began. The girls became the pirates’ playthings, repeatedly raped and terrorised with fists, hammers and knives. After tiring of them the pirates threw the three older girls overboard. Later they beat Ly and threw her into the sea because she struggled so hard to stop them raping her.

Her sister Kim had been raped by three fishermen, and Ly’s last memory of the little girl is of a sobbing, painwracked little bundle of humanity, pleading with the pirates for her life. No trace of Kim has been found.

Naked but for a pirate's shirt and a shawl, Ly kept afloat for nine hours until another fishing boat rescued her. She said the immense generosity of these Thai fishermen matched the immense cruelty of the pirates. They nursed her back to life, and when they landed at the southern Thai port of Nakhon Si Thammarat at the beginning of June they handed her over to the police, who sent her on to Ban Thad.

Frequently, the Thai military has ordered ordinary people not to give refugees any assistance, but people still find ways. Over the past week, locals in Mae Hong Son province have been doing their best to help the Karen villagers stranded at the Salween River, while the military has been trying to block them.

Thailand is far from an unwelcoming place, and many Thais go out of their way to show great kindness to those in need. But with a regime that actively flouts international law and routinely persecutes refugees, and a UNHCR leadership in Bangkok that lacks the courage to stand up to the government, the prospects for those seeking a safe haven in Thailand are desperately bleak.

Personally, I don’t know much details about the Refugees problems in thailand but mostly agreed with you that the thai regime they are never see Ethnic Karen refugees as a human being and awfully treated them lower any humanity standard..Even when Mr.Taksin Shinawatra was the Government leader, I have to say that being a Foreign Refugee in Thailand is most pathetic and misery status a human being can imagine in this world...😿❤️🌎👍

Yes, Mr.Andrew MacGregor Marshall, Thank you very much for your tireless efforts to make an insightful article like this one krub..😿❤️🌎👍