Zombie apocalypse

The story of the remarkable rise of Move Forward to become Thailand's most popular political party, and the deep state's conspiracy to stop Pita Limjaroenrat becoming prime minister.

To receive all Secret Siam newsletters and access the archive please subscribe:

I. The wrong enemy

In 2019, Thailand’s royalist elite belatedly realised they had spent a decade and a half fighting the wrong enemy.

For 15 years they had been obsessively fixated on the threat supposedly posed by Thaksin Shinawatra. By 2005, Thaksin had become so popular and powerful that he was feared and hated by leading figures in the palace, the old aristocracy, the traditional establishment and the military, and most rival billionaire businessmen too.

They conspired to topple him in a military coup in September 2006, but to their horror Thaksin didn’t just quietly give up. He never stopped fighting, and remained one of the most powerful people in Thai politics even during his years of self-imposed exile abroad.

But contrary to the paranoia of the royalist elite, Thaksin was never really a threat to the status quo. Although he continued to constantly meddle in Thai politics after being deposed, he wasn’t trying to stir up a revolution or instigate huge changes in society. During his years abroad all he was really trying to do was to strike a deal that allowed him to return to Thailand and regain the money the state had seized from him.

He didn’t want to overthrow the elite. He just wanted to join them again.

Meanwhile, a tectonic shift in attitudes was taking place, especially among younger Thais. The most recent military coup, in May 2014, provoked intense dismay and disillusionment, and the national trauma of King Bhumibol’s death in October 2016, followed by the accession to the throne of the reviled King Vajiralongkorn, had a profound impact on perceptions of the monarchy. The explosive growth in use of social media in Thailand meant that it was easier than ever before in history to see through palace propaganda and debate previously taboo issues.

The junta led by Prayut Chan-ocha clung grimly to power for almost five years before holding a general election, and engineered a constitution that was a mockery of democracy which allowed them to keep hanging on for more than four years afterwards, becoming ever more despised.

It was in this combustible environment that a new political force emerged in Thailand. Future Forward, co-founded by charismatic billionaire Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit and activist legal academic Piyabutr Saengkanokkul, was unlike any political party the kingdom had ever seen before.

Its policy agenda was eminently reasonable but remarkably radical by Thai standards. Its leaders were young — Thanathorn was 39 when Future Forward was launched in 2018 and Piyabutr was 38. Unlike other parties it had no provincial patronage networks that could mobilise votes, and it did not engage in vote buying and bribery. Instead it mainly used social media to spread its message and promote its policies.

As academics Duncan McCargo and Anyarat Chattharakul explain in their book Future Forward: The Rise and Fall of a Political Party:

Future Forward stormed the Thai political scene in early 2018... The new party challenged the ruling military junta and called for a radical overhaul of the country's economy and power structures. It had a formidable appeal to younger voters and quickly assumed the mantle of an insurgent political movement. Campaigning on a progressive platform of trimming the bloated defence budget, ending conscription and reviewing business monopolies, Future Forward generated considerable excitement…

Thanathorn and his colleagues were careful to avoid any direct challenge to the monarchy, but their progressive agenda and pledge to kick the military out of politics made it clear where they stood on the subject.

The royalist elite saw little threat from Future Forward at first. The party was brand new, it had no infrastructure to mobilise votes, and most of its election candidates were young and relatively unknown, while more established parties fielded prominent local personalities with clout and an established reputation.

They were shocked by the results of the general election in March 2019. Thaksin’s proxy party Pheu Thai won the most seats — 136, with 7.9 million votes. Prayut’s political vehicle Palang Pracharath got more votes — 8.4 million — but won only 119 seats due to the eccentricities of Thailand’s anti-democratic election system. But the real surprise was Future Forward which won 81 seats with 6.2 million votes, making it the third biggest bloc in parliament, far ahead of established parties like the Democrats and Bhumjai Thai. It was a stunning result.

As McCargo and Anyarat observed:

Few analysts had expected such a strong showing from Future Forward… Few recognised that a brand-new party could win so many votes in the provinces, with minimal campaign infrastructure on the ground.

King Vajiralongkorn and his sidekick Apirat Kongsompong, the fanatically ultraroyalist army chief, were appalled. A party that had promised to downsize the military and remove its influence on politics, with leaders known to also be in favour of reform of the monarchy even though they refrained from saying so publicly, had come out of nowhere to become a formidable force in Thai politics.

The palace and military top brass were terrified of Thailand’s youth, who were increasingly rejecting the traditional Thai values of obedience, deference and reverence for the monarchy. Most young people — and many older people too — despised Vajiralongkorn, an absentee monarch who spent almost all of his time in the vast Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl in Bavaria with a harem of more than 20 women, and who was frequently photographed cycling in very skimpy briefs or wearing a crop top and sporting fake tattoos, apparently indulging a fetish for public semi-nudity.

Meanwhile, open discussion and criticism of the monarchy was exploding on social media, and the ongoing protests in Hong Kong, also mainly youth-led, provided inspiration for disaffected Thais.

According to Piyabutr, shortly after the election a senior government figure told him that unless he and Thanathorn withdrew from public life and left the country for five years, Future Forward would inevitably be dissolved. It was only a matter of time.

In September 2019, Thanathorn and Piyabutr held secret talks with Apirat over dinner, trying to resolve tensions and seek some mutual understanding.

It didn’t go well. The following month, Apirat gave a hysterical speech in which he claimed a sinister alliance of former communists, leftist academics, corrupt politicians and foreign provocateurs was conspiring to destroy Thailand using “hybrid warfare” tactics that included fake news and propaganda.

He wept as he proclaimed his devotion to Vajiralongkorn, and burst into tears again while claiming his father Sunthorn was a war hero who was “shot by the communists while he was piloting a helicopter and protecting his nation”. In fact his father was a buffoon who was among a group of generals who deposed an elected government in a coup in 1991, and who regularly appeared in the gossip pages of Thai newspapers due to a public spat between his wife and mistress. There is no record of him ever being wounded in battle.

Apirat warned that Thailand’s stability could be disrupted by activists using similar tactics to the protesters fighting for democracy in Hong Kong. And he tried to smear Thanathorn by noting that a prominent politician had recently met Hong Kong democracy activist Joshua Wong, and pondering aloud whether they were in cahoots to cause chaos in their countries. Apirat didn’t name the politician, whose image was greyed out in the slide he displayed on screen, but everybody knew he was talking about Thanathorn.

Vajiralongkorn and Apirat had become so afraid of Future Forward and the risks of a Hong Kong-style uprising in Thailand that they decided to take decisive action.

The method they chose had been employed several times already by the palace in the 21st century to neutralise enemies without leaving obvious fingerprints — outsourcing the job to the Constitutional Court.

Thailand’s justice system has always favoured those with wealth and royal connections, but the courts became particularly politicised after King Bhumibol gave two speeches in April 2006 calling on judges to resolve the country’s political conflict. This heralded the beginning of an era of political judicialisation in which the Constitutional Court intervened numerous times to try to torpedo the political hopes of Thaksin Shinawatra — annulling general elections in 2006 and 2014, removing Samak Sundaravej as prime minister and then dissolving the People’s Power Party in 2008, sabotaging constitutional amendments in 2013, and dissolving the Thai Raksa Chart Party in 2019.

Now, Vajiralongkorn ordered the court to deal with Thanathorn and Future Forward.

The judges duly did what they were told. In November 2019, Thanathorn was stripped of his seat in parliament by the Constitutional Court for allegedly owning 675,000 shares in V-Luck Media, an obscure company whose only two publications, lifestyle magazine Who! and the Nok Air inflight magazine, had ceased publication two years earlier. The company was preparing to close, pending collection of some debts it was owed.

There was no conceivable way Thanathorn could have used his shareholding in this company to gain any kind of unfair advantage in Thai politics. He had managed to build up a huge following for himself and his party through shrewd use of social media. The claim that he could gain an advantage through a negligible shareholding in a zombie company that was no longer publishing any magazines, and had no influence even back in the days when it was publishing magazines, was patently absurd.

But when Vajiralongkorn wants something done, the deep state obliges.

Having decapitated the party by removing Thanathorn, the royalist elite turned its attention to destroying Future Forward.

A case accusing the party of links to a global conspiracy involving the mythical Illuminati secret organisation was so ridiculous that even Thailand’s pliant judiciary had to throw it out, but an opportunity arose in February 2020 when the Constitutional Court was due to rule on whether a 191.3 million baht loan from Thanathorn to Future Forward was an illegal donation. The whole case was ridiculous because the payment was clearly a loan, which was allowed, not a donation, but the palace ordered the judges to ensure a guilty verdict with a punishment as harsh as possible.

On February 21, 2020, as expected, the Constitutional Court dissolved the Future Forward Party and banned Thanathorn and other party executives including co-founder Piyabutr and spokeswoman Pannika Wanich from politics for 10 years.

The palace and military thought they had neutralised the threat from Future Forward and the new generation of Thais demanding change. They could not have been more wrong.

II. Wildfire

“This is not the end, but the beginning,” declared Piyabutr after the verdict. “This will spread like wildfire.”

He was right. The verdict provoked a remarkable wave of protests at university campuses and schools across Thailand, and Thai communities around the world.

The great irony of the events of 2020 in Thailand is that by trying to crush any prospect of a mass protest movement demanding democracy, Vajiralongkorn and Apirat had managed to achieve the opposite of what they intended. They had unleashed the very thing they were desperately trying to prevent.

On February 24, large “flash mobs” were held at Thammasat University, Chulalongkorn University, Ramkhamhaeng University, Kasetsart University, Srinakharinwirot University and Prince of Songkhla University. Within days there had been protests at more than two dozen universities. There were rallies at two prestigious Bangkok schools — Triam Udom Suksa School on February 27 and the all-girl Suksanari School on February 28.

Each institution had its own Twitter hashtag to organise rallies, and the three-finger “Hunger Games” salute was ubiquitous at the flash mob events. They were the biggest protests against the Thai regime since Prayut and his allies had seized power in a coup in 2014.

There was also an unprecedented new — and explosive — element in many of the protests: students held up signs and wrote slogans challenging the monarchy. The anger at Vajiralongkorn that had been simmering on social media was now overflowing into physical protests on university campuses.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus pandemic was sweeping the globe. The German state of Bavaria, where Vajiralongkorn and his vast entourage were living in a hotel in the Alpine resort town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, announced an emergency lockdown on March 20, with hotels and restaurants closed, and residents only allowed to leave their homes for essential reasons. But instead of leaving Germany and heading back to Thailand, Vajiralongkorn continued his 13-year holiday in Bavaria.

On March 18 he had applied for a special permit from the Bavarian authorities to remain at the Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl. It was granted, with the justification that the king and his entourage were “a single, homogenous group of people with no changes”.

Vajiralongkorn’s life of luxury and hedonism in Bavaria was funded by Thai taxpayers. The new national budget bill, announced in March, included nearly 30 billion baht of spending on the monarchy — an extraordinary 0.93 percent of the total national budget. No other country in the world spends a larger share of taxpayer money on its royal family.

Outrage at the king’s behaviour exploded online after exiled historian Somsak Jeamteerasakul, one of the foremost experts and commentators on the Thai monarchy, published a tweet about Vajiralongkorn’s antics in Germany, with the hashtag #กษัตริย์มีไว้ทําไม — #WhyDoWeNeedAKing? Over the next 24 hours the hashtag was used more than 1.2 million times as Thais vented their disgust. It was the most overt online challenge the Thai monarchy had ever faced.

Furious about the unprecedented protests against him in Thailand and around the world, Vajiralongkorn ordered his notorious security chief Jakrapob Bhuridej to organise the murder of a Thai activist abroad to send a warning that open defiance of the monarchy must end. The victim they chose was Wanchalearm “Tar” Satsaksit, a 37-year-old activist living in exile in Phnom Penh. He wasn’t even a particularly vocal critic of the monarchy, but he was an easy target because of the lawlessness of Cambodia.

On June 4, 2020, he left his Phnom Penh apartment to buy meatballs at a roadside stall, while chatting on his mobile phone to his sister Sitanun in Thailand. Suddenly a black SUV pulled up and several armed men jumped out, grabbing Wanchalearm before driving away. Over the phone, his sister heard him repeatedly shouting: “I can’t breathe.” For thirty minutes she stayed on the call, listening to muffled noises, before the line went dead. Wanchalearm has never been seen again. He is presumed dead.

Like the dissolution of Future Forward, the enforced disappearance of Wanchalearm Satsaksit was another disastrous strategic blunder by Vajiralongkorn and his allies. They thought it would put an end to mounting opposition to the monarchy. Instead, it poured fuel on the flames.

There was uproar in Thailand. #saveวันเฉลิม quickly became the top hashtag on Thai Twitter with more than half a million tweets after the kidnapping, and #ยกเลิก112 soon started trending too — a call to scrap the archaic lèse majesté law used by the palace for decades to try to stifle dissent.

Posters and street art with Wanchalearm’s face appeared all over Bangkok and beyond. The Student Union of Thailand organised a flash mob protest at the skywalk beside the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre the day after Wanchaleram’s abduction. Police tried to disperse the crowd, citing the need for social distancing during the pandemic, but the protesters refused to be intimidated. Three days later dozens of people led by prominent activist Somyot Prueksakasemsuk gathered outside the Cambodian embassy in Bangkok, demanding answers. Rangsiman Rome, a democracy activist who had joined Thanathorn’s Future Forward movement and become an MP, raised the issue in parliament.

Reuters reported that Wanchalearm’s disappearance had “reignited protests against Thailand’s military-royalist elite”. It galvanised and radicalised the democracy movement, and dragged the reputation of the Thai monarchy to its lowest point in history. It was the moment when many younger Thais decided enough was enough. It was time to fight.

The second half of 2020 saw unprecedented mass rallies demanding reform of the monarchy. Protesters held banners with coded messages criticising Vajiralongkorn, and over time the slogans and images became increasingly bold.

In a watershed moment in Thailand’s political evolution, student activist Panusaya "Rung" Sithijirawattanakul took to the stage at a rally attended by thousands at Thammasat University’s Rangsit campus to read a 10-point manifesto for royal reform. Nobody had dared to do anything like this since a group of civilian bureaucrats and military officers rose up to end Siam’s system of absolute monarchy back in 1932.

In September, one protest at the royal cremation ground at Sanam Luang, right beside the Grand Palace, attracted more than 40,000 people.

Week after week through October, November and December, tens of thousands turned up to mass rallies demanding reform of the monarchy and military.

The regime responded with increasing violence. Police began routinely using tear gas and water cannons, and firing rubber-coated bullets, to disperse peaceful protesters. Off-duty police and soldiers, and thugs-for-hire from the provinces, were brought into Bangkok in trucks and buses ahead of rallies to intimidate protesters and try to provoke clashes. The increasingly paranoid Vajiralongkorn was bizarrely terrified of the prospect of protesters setting foot on “royal ground” so vast walls of shipping containers were constructed around royal sites ahead of protests. It vividly symbolised the monarch’s contempt for the wishes of the people.

In November 2020, Vajiralongkorn ordered Prayut to announce the resumption of prosecutions for lèse majesté under the draconian Article 112 of Thailand’s criminal code. The king had told the government and judiciary to suspend use of the law in 2017, a gesture apparently intended to create an impression of compassion and magnanimity, although it led to no substantive improvement in freedom of speech because critics of the monarchy were just prosecuted for sedition or computer crimes instead. But by the end of 2020, Vajiralongkorn was so worried he demanded hardline tactics, with lèse majesté being used unsparingly to lock up leading activists and decapitate the protest movement. Courts were also ordered to routinely refuse bail.

Protests continued throughout 2021. They were smaller in scale than the biggest rallies of 2020, but nevertheless were met with a heavy handed and violent response from riot police who often fired rubber-coated bullets at pointblank range. Some protesters became bolder and more audacious, defacing pictures of Vajiralongkorn with graffiti and sometimes setting them on fire.

The sheer number of activists charged with lèse majesté forced the regime to relax its blanket ban on bail — it would have damaged the image of the palace and government even more if scores of young people were being imprisoned without trial. So the authorities focused on the leaders of the democracy movement, in particular Anon Nampa, Panusaya “Rung” Sithijirawattanakul, Parit “Penguin” Chiwarak, Jatupat “Pai Dao Din” Boonpattararaksa, Benja Apan and Panupong “Mike” Jadnok. Some of them spent more than 200 days in jail during 2020 and 2021.

On August 10, 2021, in an extraordinary ruling, the Constitutional Court ruled that calls for royal reform from Rung, Penguin and Mike were an attempt to overthrow the monarchy. “Any actions that seek to undermine or weaken the institution show intentions to overthrow the monarchy,” the judges said in their ruling. Sunai Phasuk of Human Rights Watch called it a “judicial coup” and the BBC’s Jonathan Head said:

This ruling effectively closes down any space in Thailand for public discussion of the monarchy, and lays the three activists cited by the court open to charges of treason, which carries the death penalty.

Also in August, disaffected youths in the impoverished Din Daeng area of the capital began gathering after dark almost every night for months to battle police. They were mostly motivated by economic hardship, a lack of opportunities and anger at police brutality but they also wanted to protest against the Prayut regime, and some of them set pictures of Vajiralongkorn ablaze. They formed a loose protest group that called itself Talugaz, which roughly translates to breaking through tear gas. The name was also a reference to Pai Boonpattararaksa’s protest group Talufah, which means breaking through the sky, a symbolic term for challenging the monarchy.

By the end of 2022, mass rallies had mostly fizzled out. A few have been held since, but the extraordinary scenes of 2020 have not been repeated, for now.

There are several reasons — fatigue and exhaustion, the repeated arrest and detention of protest leaders, the disproportionate violence of the police response, and disagreements among different protest groups over tactics and strategy.

But the rise of a mass movement brave enough to openly demand reform of the monarchy has transformed Thailand. Things can never go back to the way they were before.

Evidence of the change in attitudes is everywhere. Hardly anyone bothers to stand up in cinemas now when the royal anthem is played before a movie. Young people who rushed to get tattoos showing their reverence for Bhumibol following his death in 2016 are now ashamed of them and are getting them covered up or removed. Social media is still buzzing with open criticism of the monarchy, despite the risks.

The era of reverence for the king is over forever.

III. Moving forward

The remarkable electoral success of the Move Forward party is a direct result of the profound societal change in perceptions of the monarchy and military in Thailand.

When Future Forward was dissolved and 16 of its top leaders banned from politics for a decade, the royalist elite hoped they had successfully dealt with the threat from the upstart party and Thailand could return to politics as usual, with corrupt coalitions of convenience governing the country and keeping the kingdom trapped in the same old status quo in which they profited at the expense of most of the population.

In a final news conference on the evening of February 21, 2020, Thanathorn removed the Future Forward lapel pin from his suit collar and handed it to Pita Limjaroenrat, an affable 39-year-old Harvard-educated businessman, who was his choice to lead the remnants of the party.

McCargo and Anyarat recount the moment in their book on Future Forward:

Pita declared that he was not a superstar like Thanathorn or Piyabutr, but that he and the remaining MPs hoped collectively to become a group of shining stars. The modest declaration clearly reflected Pita’s awareness that none of the remaining MPs could match the star power or personal charisma of the original leadership triumvirate — nor did they have nearly as many followers on Twitter.

Pita and his comrades took over a defunct political party founded in 2014, Ruam Pattana Chart Thai, and renamed it Move Forward. They unveiled a logo similar to Future Forward’s, and 55 of Future Forward’s 65 MPs joined the new party.

Pita and his colleagues in Move Forward were supposed to have no contact with the banned executives of Future Forward. But the new party’s secretary-general, Chaitawat “Tom” Tulathon, was an old friend of Thanathorn and acted as an informal go-between.

After its launch, it was unclear whether Move Forward would be able to muster much support among the electorate. In their book published in 2020, McCargo and Anyarat wrote:

It remained unclear how many Future Forward supporters would continue to support the Move Forward party, in the absence of the “stars” they fell in love with… The challenge for Move Forward was to retain the support of former Future Forward voters, many of whom had been enthralled by Thanathorn and Piyabutr — would they stick with a new version of the party under different leadership?

In an analysis for ISEAS in April 2020, Termsak Chalermpalanupap also argued that Move Forward faced an uphill struggle:

Pita and the Move Forward Party face daunting challenges: moving out of Thanathorn’s shadow; fund-raising under stringent constraints; and recruiting as many as 100,000 members from the disinterested populace in order to continue struggling for political reforms in parliament and to establish a nation-wide presence through participation in local government elections.

You can download the full analysis here:

More doubts were raised when Pita said in an early interview that Move Forward would be less aggressive and more pragmatic than Future Forward. Some supporters who had been inspired by the courage and idealism of Future Forward felt let down. According to McCargo and Anyarat:

In many respects, it made sense for Pita Limjaroenrat to succeed Thanathorn. He was also a proven entrepreneur with strong academic credentials and a social conscience. Like Thanathorn, he had inherited and successfully transformed a family business following the death of his father. Pita was bright, good-looking and well spoken, with a fan base of admirers and an easy social manner. But while Thanathorn's sincerity and idealism were beyond doubt, Pita was a more mainstream, pragmatic and technocratic figure. In the end, it was hard to imagine Pita setting the hearts of the young generation on fire the way Thanathorn and Piyabutr had done. Pita was a logical, if not an emotional, successor…

The Future Forward leaders had been activists, buzzing with an energy that the technocrats running Move Forward lacked. As leader, Pita adopted a relatively low profile, claiming he was trying to support his parliamentary colleagues to be more active.

But just like many other Thais, Pita became more radical as the extraordinary events of 2020 unfolded. Move Forward had to adapt to accommodate the aspirations of the millions of younger Thais who wanted real change, including reform of the monarchy.

Pita gave considerable leeway to two of the most radical MPs in his party — Wiroj Lakkhanaadisorn, who became Move Forward spokesman, and Rangsiman Rome, who first became widely known in Thailand as one of the leading student activists who courageously opposed the 2014 coup. Here is Rome with fellow activists at a protest outside the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre on the first anniversary of the 2014 coup:

Wiroj and Rome both made use of parliamentary privilege to expose the crimes and corruption of the government and ruling elite.

At a censure debate in parliament on February 25, 2020, Wiroj presented extensive evidence of systematic attempts by the military to spread disinformation — known as information operations or IO.

He presented a leaked document showing that the notorious Internal Security Operations Command played a key role in funding and conducting cyber warfare against activists, politicians, and academics working to promote the peace process in the Deep South. Wiroj accused prime minister Prayut Chan-ocha and his government of using government funds to harass the public and incite division. Other evidence included including a clip in which army officers confessed to their involvement in the IO campaign, private LINE chats among officers encouraging the dissemination of fake news, and leaked official government documents relating to the campaign.

The Bangkok Post said Wiroj’s debate performance had made him an “overnight sensation” and “shocked many viewers”. An unusually strongly worded editorial in the usually supine newspaper declared:

The exposure by Mr Wiroj startled those who watched the debate. The facts are simple but sickening. This seems to be a systematic effort to spread hate speech and fake news, and turn people from opposing political camps against each other. At the same time, the alleged IO promotes one-sided information that puts the government and the army in a positive light.

The revelations were partially confirmed later in the year when Twitter shut down 926 accounts linked to the Thai army which had been “engaging in amplifying pro-RTA and pro-government content, as well as engaging in behavior targeting prominent political opposition figures”. The move followed a detailed report by the Stanford Internet Observatory.

In another bold performance that won the support of many younger voters, during a parliamentary debate in June 2020, Rome accused the government of complicity in the disappearance of Wanchalearm Satsaksit in Cambodia:

The government doesn’t bother to find him. Since general Prayut Chan-ocha assumed power, there have been nine kidnappings like this so far. Seven of them remain missing, while two of them are confirmed dead without any explanation from the government.

The abduction and presumed murder of Wanchalearm was a crucial catalyst for the mass protests of 2020, and Rome’s intervention in parliament won Move Forward even more respect from pro-democracy Thais.

On February 10, 2021, Move Forward adopted its boldest position yet on the monarchy, proposing an amendment to the lèse majesté law to sharply reduce the maximum punishment and stop Article 112 being abused. Under the proposals, honest criticism of the monarchy would be allowed, only the Royal Household Bureau would have the authority to file lèse majesté complaints to the police, and the maximum penalty for defaming or threatening the king would be a year in jail, a fine of 300,000 baht, or both.

“This is a proposal that we think all sides can talk about, can accept and live with, and it will ease the political tension,” Move Forward secretary general Chaithawat said.

Inevitably, there was outrage from ultra-royalists, with Thai Pakdee party leader Warong Dechgitvigrom saying: “Some groups wanted to topple the monarchy, but they are telling society that they are only want to reform.”

The amendment had no chance of being passed by either chamber of parliament, with both the House of Representatives and the Senate dominated by performative royalists. In the end it didn’t even get that far — the amendment was rejected by the House of Representatives Secretariat and the Office of House Meetings on the grounds that it was unconstitutional, based on Article 6 of the charter which states: “The King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated.”

But it was a courageous move that won Move Forward even more popularity among Thais eager for reform. Even Future Forward had never tried to debate the issue of lèse majesté in parliament — everybody knew that the party’s leaders favoured reform of the law and the monarchy itself, but they thought it was too controversial an issue to raise for the moment. Largely thanks to the wider space for debate and discussion opened up by the protest movement during 2020, Move Forward was now even more radical than its predecessor.

Another censure debate was scheduled for February 16 to 19, 2021, with voting on February 20. Ahead of the debate, Wiroj said Move Forward would raise the government’s disastrous vaccine strategy which was dangerously overreliant on Siam Bioscience, a company owned by the king, and would also challenge the government on abuse of the lèse majesté law:

We will take to the floor and speak about the intimidation of protesters by the Emergency Decree and Article 112. Its enforcement is not transparent. Different MPs will discuss the issue from different perspectives…

We have studied lese majeste laws used in other countries and consulted with academics, so we’ll know what they think. The punishment has to be suitable for modern context. It cannot be disproportionately high.

None of the other opposition parties who claimed to be pro-democracy dared to broach such a sensitive subject. Pheu Thai and Seri Ruam Thai both ruled out raising the issue of the monarchy in the debate.

The regime was apoplectic about Move Forward’s plans. Chief government whip Wirat Rattanaset vowed that if opposition parties made any reference to the monarchy at all, by criticising the regime’s use of lèse majesté or accusing Prayut of exploiting Siam Bioscience’s royal ownership to shield himself from criticism over the botched vaccine rollout, all the government’s MPs would immediately protest and halt the discussion. Paiboon Nititawan, deputy leader of the ruling Phalang Pracharath Party, said the government would use Article 69 of the parliamentary rules, which forbids any legislator from “referencing His Majesty the King without due cause” to block any attempt to mention the monarchy. Going a step further, Sira Jenjakha, a government MP representing Bangkok, said that if any opposition censure motion contained a reference to the royal family he would file a lèse majesté complaint against all the legislators who signed it. Hardline royalist Warong Dechgitvigrom made a similar threat.

During the debate, which ran from February 16 to 19, Paiboon and Sira tried to silence Wiroj when he criticised vaccine procurement strategy and accused Prayut of using the lèse majesté law to hide behind the palace and avoid scrutiny of the vaccine plans. Sira even moved seats to be close to Wiroj as an intimidation tactic.

Meanwhile, in another bombshell speech during the debate, Rome exposed palace involvement in widespread corruption in police promotions.

He discussed how the palace is directly involved in police promotions via a system of “elephant tickets” — documents issued by Major General Torsak Sukvimol, head of the Ratchawallop Police Retainers of the Royal Guard 904, the special military and police force directly commanded by Vajiralongkorn. Torsak is the younger brother of Air Chief Marshal Satitpong Sukvimol, one of the king’s closest and most powerful advisors, who heads the Crown Property Bureau and is Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household Bureau. According to Rome, Satitpong runs the elephant ticket scheme with Torsak.

Rome shared a document from 2019 in which Satitpong asked Vajiralongkorn to authorise promotions and awards for 20 police officers. This was granted, in a document signed by both King Vajiralongkorn and Queen Suthida, although in the version shared by Rome their signatures were redacted.

Rome also discussed how hundreds of police officers had been ordered to do special training for several months at Thaweewattana Palace to join the Ratchawallop Police Retainers, with anyone who refused punished by having to go on a lengthy disciplinary course.

Predictably, there was pandemonium in parliament as Rome gave his speech, and he was interrupted several times even though he only identified those involved in the elephant ticket scheme by their initials. Parliament speaker Supachai Phuso ordered him to avoid further mention of the monarchy. Prawit Wongsuwan, who has been involved in the corrupt sale of military and police promotions for years along with his brother Patcharawat, was so infuriated that he stormed out.

Daring to share these revelations showed incredible bravery. The regime had already threatened to file lèse majesté charges against him. Suphon Attawong, the former Red Shirt activist “Rambo Isaan” who changed sides and became assistant minister at the PM’s office, told reporters: “Our legal team has looked into it and concluded that the information is sufficient for prosecution under Article 112.”

The risks went far beyond lèse majesté. In a news conference after the debate Rome mentioned not only the Sukvimol brothers but also Vajiralongkorn’s murderous security chief Jakrapob Bhuridej and his brother, police Major General Jirapob Bhuridej, who heads the Crime Suppression Division. These men hate being in the spotlight and were certain to be enraged by Rome’s accusations. They have a history of violence against their enemies.

Rome acknowledged the danger he faces, saying:

I’m aware that this could be the most dangerous mission of my life, but since the people already chose me for this job, I have to carry out my duty to the best of my ability. I don’t know what will be the consequences of my action from now. I don’t know what waits for me in the next three days. I don’t know what will happen in the next three months. I don’t know if I’ll still be able to speak on behalf of the people. But no matter what happens, I don’t regret carrying out my duty today.

A year later, at a censure debate in February 2002, Rome again revealed explosive information. This time his revelations were about major general Paween Pongsirin, a senior police officer who was tasked with investigating the kidnap, extortion and trafficking of Rohingya refugees trying to reach Thailand and Malaysia by boat, after a mass grave was found on a mountain in Songkhla province.

Paween’s investigation led to the arrest of 91 people, most notably major general Manas Kongpan, a senior army officer and director of ISOC Region 4, who was later sentenced to 82 years in prison. Manas was extremely well connected with links to the palace and Prayut’s sidekick Prawit Wongsuwan. Paween came under intense pressure from powerful figures in the government, military and palace to abandon his investigation. Fearing his life was in danger, he fled Thailand in November 2015 and was granted political asylum in Australia in 2017.

Rome shared a copy of the statuary declaration Paween submitted as part of his asylum application in Australia. It was heavily redacted, probably because some passages discussed palace interference in the case and it would have been too dangerous for Move Forward to reveal this information.

On October 15, 2022, Pita held a news conference to outline the proposed reforms that would be central to Move Forward’s election campaign in 2023. They included amendment of the lèse majesté law, an amnesty for political prisoners and those convicted of violating Article 112, a ban on former military officers holding a cabinet position within seven years of their retirement, the abolition of compulsory military service, and the dissolution of ISOC.

An incident in March 2023 illustrated the increasing boldness of Move Forward in addressing the issue of lèse majesté.

Pita was preparing to give a speech at Laem Chabang Municipal Park in Chonburi Province when two young activists, Tantawan “Tawan” Tuatulanon and Orawan “Bam” Phuphong, climbed onstage.

The pair had come to prominence the previous year with a novel form of small-scale protest — they would conduct informal surveys in public places, carrying a large sheet of white card with a controversial question written on it, and handing out small stickers to passers-by for them to indicate their answer.

In February 2022 they held a survey in the Siam Paragon mall asking: “Do you think royal motorcades cause problems?” Siam Paragon is a particularly sensitive place to protest as it’s built on land owned by the king’s sister Sirindhorn, who also owns a large share of the mall. Along with seven other activists they were charged with lèse majesté, sedition and resisting arrest.

In January 2023 they went to Ratchadaphisek Criminal Court to file for revocation of their bail. They poured red paint over themselves, and declared they would return to jail where they would begin a hunger strike until all pro-democracy activists had been freed from detention.

Tawan and Bam went without food for 52 days, finally ending their hunger strike on March 11. Less than two weeks later they approached Pita on stage in Chonburi with a survey asking whether the lèse majesté law should be abolished or retained.

Pita welcomed them onto the stage and allowed them to address the crowd. He placed his sticker in the “Abolish” column, as did all 10 of the Move Forward candidates in Chonburi province who were with him on the stage. But he added: “However, I must apologise, but the party must push for amendments first.”

Thailand’s next general election was due to be held in 2023, and with Prayut’s unpopular government haemorrhaging support, Pheu Thai was confident of winning a landslide victory.

In a video call with Pheu Thai members in October 2021, Thaksin told them they would need to achieve an overwhelming electoral victory. The magic number was 375 seats, which would mean the 250 junta-appointed senators would be powerless to block Pheu Thai’s choice of prime minister. A landslide, Thaksin said, would allow Pheu Thai to form a government “without resistance from them”.

“A landslide win. That's the only thing that Pheu Thai wants,” declared Thaksin’s daughter Paetongtarn at the annual Pheu Thai assembly in April 2022.

It wasn’t a completely implausible aspiration — Thaksin’s Thai Rak Thai party had won 377 seats in the 2005 general election — but as the May 2023 polls approached, Pheu Thai began to lower its expectations a little, although it still expected a landslide.

“Pheu Thai is now seeking a popular mandate and aims to win at least 310 House seats to get rid of the Prayut regime and form a Pheu Thai government,” party leader Cholnan Srikaew told the Pheu Thai general assembly on March 9.

Most analysts, too, believed that Pheu Thai was on course for an overwhelming victory. Termsak Chalermpalanupap, a fellow at ISEAS who had previously spent two decades working at the ASEAN secretariat, wrote a month ahead of the election that Pheu Thai “looks certain to win the largest number of seats in the House of Representatives”.

Even usually reliable observers were convinced Pheu Thai was on track for victory. “The fact that the main opposition Pheu Thai Party is on course to win again is the most likely political outcome in the past 20 years,” Chulalongkorn University professor Thitinan Pongsudhirak predicted in March 2023. “Poll results not only point to another Pheu Thai triumph in two months, but a victory by too big a margin to be denied a role in the resultant coalition government.” Jonathan Head, the veteran BBC correspondent in Bangkok, wrote on May 11 — just a few days before the polls — that Pheu Thai was “far ahead of all its rivals”.

So the results of the election were a stunning surprise. As Allen Hicken and Napon Jatusriptak observed in an analysis published in the ISEAS journal Contemporary Southeast Asia: “Thailand’s general elections on 14 May 2023 marked a seismic shift in its political landscape.”

Since his launch of Thai Rak Thai in 1998, parties backed by Thaksin had won every single general election in Thailand by a wide margin. But not this time.

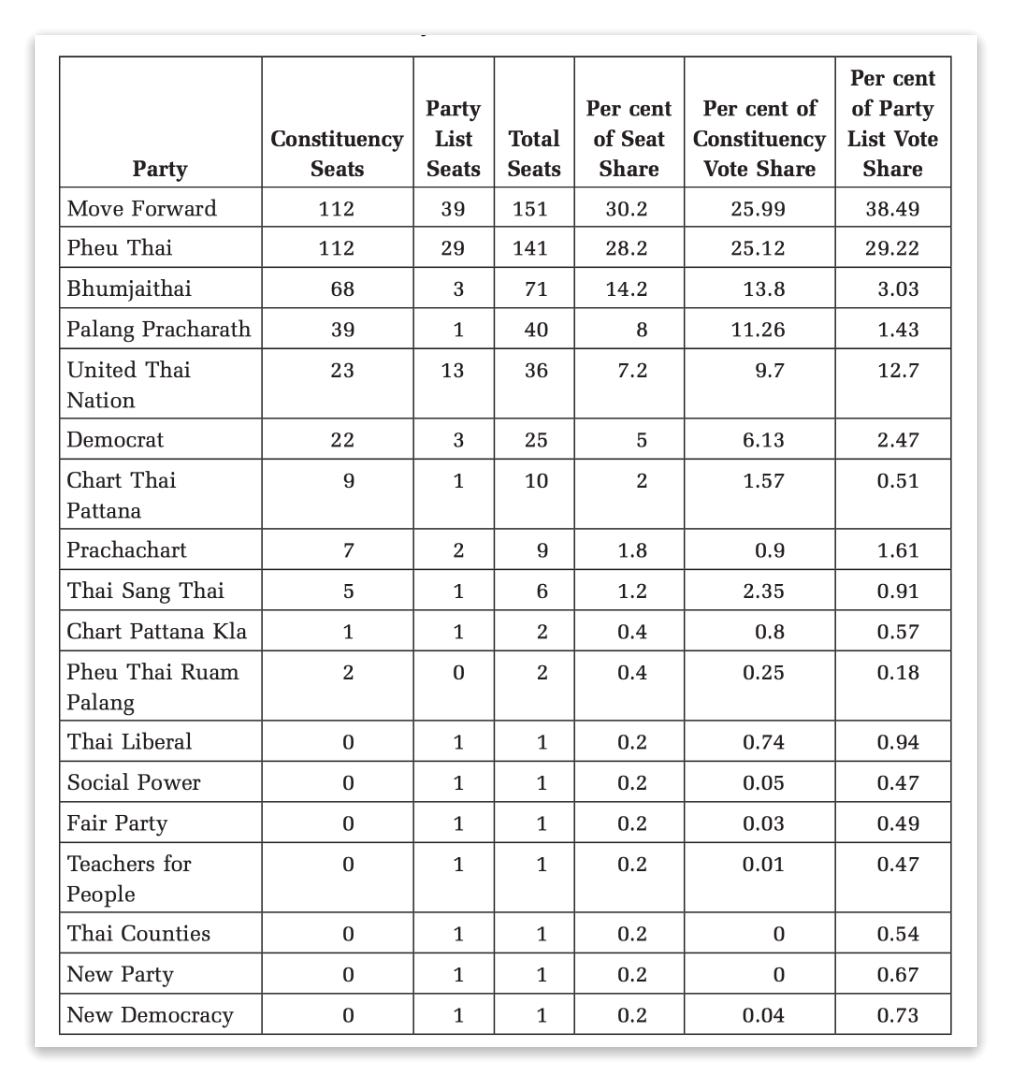

Move Forward, which had only been in existence for two years and had no nationwide network to mobilise votes, achieved an extraordinary victory, with an incredible 14.44 million party list votes, winning 151 seats in parliament and becoming Thailand’s biggest party in terms of MPs in the House of Representatives.

Pheu Thai came second with 141 seats, and the two political vehicles of the coup leaders who had fallen out with each other a couple of years before the election, Prawit’s Palang Pracharat and Prayut’s United Thai Nation, performed poorly with 40 and 36 seats respectively.

As Hicken and Jatusripitak noted:

This disruptive outcome was grounded in two key transformations in the political landscape: longstanding regional and political divisions, often driven by economic concerns and polarizing views on Thaksin, were transcended by ideological rifts over structural reforms related to the monarchy and the military; and traditional local power dynamics — underpinned by money politics, patronage networks and political dynasties — were challenged by social media and social movements which have become driving forces in shaping political discourse, party-building and campaigning.

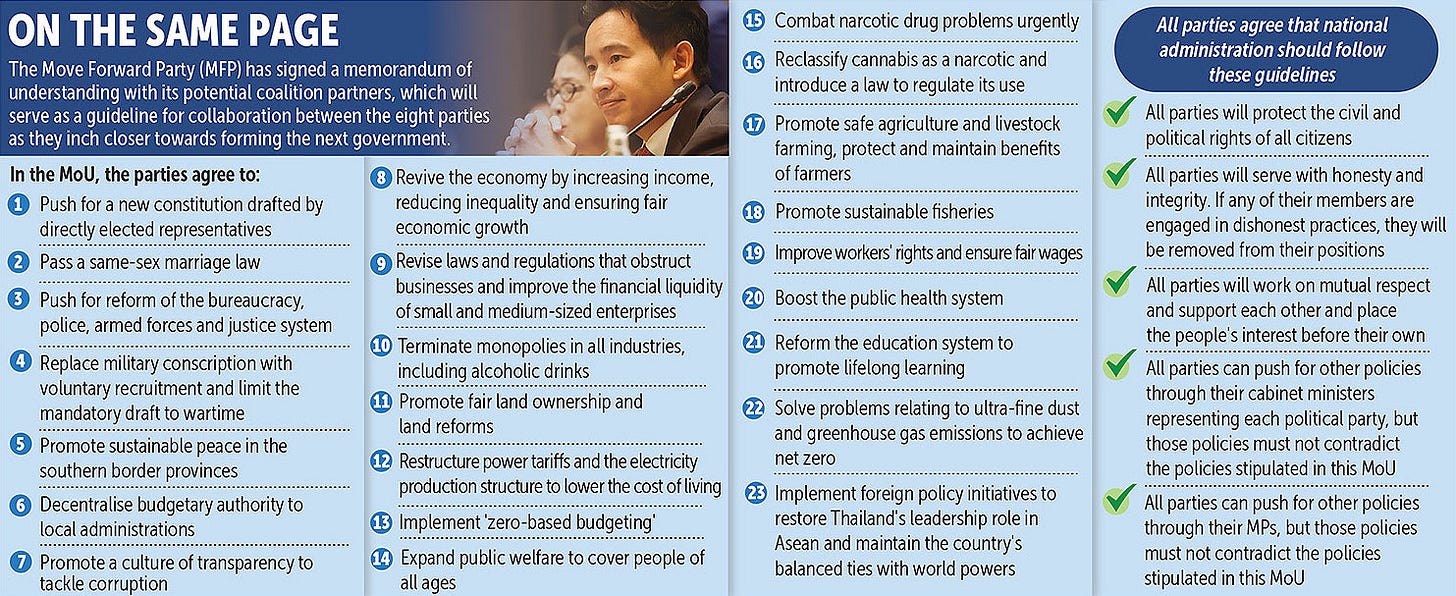

Move forward soon assembled a coalition with Pheu Thai and six smaller parties — Prachachart, Thai Sang Thai, Seri Ruam Thai, Fair, Palang Sangkhom Mai and Pheu Thai Ruam Phalang — to create a formidable bloc with 312 seats in the 500-member parliament.

The coalition parties agreed on a 23-point Memorandum of Understanding setting out their policy priorities. It was unveiled at a packed news conference at the Conrad Hotel on May 22, a date chosen because it marked the ninth anniversary of the 2014 coup in which Prayut and Prawit overthrew the democratically elected Pheu Thai government of Yingluck Shinawatra and seized power for themselves, presiding over nearly a decade of political repression, rampant corruption and economic stagnation which voters had now decisively rejected.

This graphic from the Bangkok Post lists the 23 points:

Thailand’s royalist elite was shocked. But a conspiracy was already under way to sabotage Pita’s hopes of becoming prime minister.

IV. Voodoo magic

The popularity of Move Forward surged from mid-2020 onwards as mass protests demanding democracy and reform of the monarchy transformed Thailand forever. With the party’s policy platform of curtailing the clout of the monarchy and military gaining traction among millions of voters, the panicked deep state swung into action.

They hatched a plan to use the same tactic they had successfully employed to kick Thanathorn out of politics — they would try to get Pita disqualified as member of parliament via allegations that he unlawfully held shares in a media company.

This would require some voodoo magic, because iTV, the company in which Pita held a tiny 0.0035 percent stake, was a defunct former television station that no longer had an operating license, and had not broadcast anything or made any income from media operations for more than 15 years. The shares were not even in Pita’s name — they had been owned by his father, and passed into Pita’s possession because he was executor of the estate after his father died in 2006.

So for the conspiracy to work, iTV had to be somehow raised from the dead.

iTV was launched in 1995 as Thailand’s only independent television station, focusing exclusively on news, with Siam Commercial Bank, the Crown Property Bureau, the Pacific Communications firm owned by palace public relations advisor Piya Malakul and Nation Multimedia Group as major shareholders. To safeguard its independence, shareholders were barred from owning more than 10 percent of the company. But iTV began haemorrhaging money after the 1997 economic meltdown and soon became insolvent.

Desperate to shield the shareholders linked to the palace from damaging losses if iTV collapsed, the Democrat Party government led by Chuan Leekpai ended the 10 percent cap on shareholdings to try to attract a buyer. In 2000, Thaksin stepped in and his Shin Corp conglomerate bought most of iTV for $60 million.

He significantly overpaid — the assets of iTV were worth far less and the company was insolvent — but Thaksin had his reasons. He was able to further ingratiate himself with the palace by bailing out Siam Commercial Bank and the Crown Property Bureau, and it also gave him a platform to promote his bid to become prime minister in the 2001 general election.

Thaksin wasted no time in compromising iTV’s editorial independence, pressuring journalists to downplay negative news about his Thai Rak Thai party and give him favourable coverage. Some journalists resisted and 21 of them were fired. Shin Corp also gained permission to increase the amount of entertainment content on iTV and reduce the amount of news.

But by 2006, as Thailand’s establishment turned against Thaksin, iTV was accused of breaching regulations and hit with a fine of nearly $3 billion. After the military toppled Thaksin in a coup, the new government said in 2007 it would take over iTV if the fine was not paid, and appointed a new executive board made up entirely of civil servants.

In March 2007, iTV was taken off the air permanently and has not produced any media content ever since. The station was replaced in January 2008 by the newly created Thai Public Broadcasting Service, or Thai PBS. Its shares were delisted by the Stock Exchange of Thailand in 2014.

The only reason the company still exists is because it was fighting an interminable legal case against the Office of the Prime Minister to avoid facing the nearly $3 billion fine. It was just a zombie company, with no media operations, only still in existence because it was trapped in legal limbo. Last month, on January 25, the Supreme Administrative Court upheld earlier rulings that iTV did not have to pay the fine, meaning that it will probably soon be dissolved forever.

Pita Limjaroenrat’s father died in 2006. Pita acted as executor of the estate, and among the shareholdings belonging to his father was a negligible stake of 42,000 shares in iTV. According to Pita, he tried to sell the shares but was unable to find a buyer, and he didn’t think much about them in the years that followed because the company was defunct anyway.

As they sought a way to sabotage his political prospects, enemies of Pita found out he held he held 42,000 shares in iTV. They scented blood. Pita had declared the shareholding ahead of becoming a member of parliament in 2019, and it had not led to any problems for him because everybody knew iTV was defunct and no longer had any media operations. But if his enemies could somehow find a way to revive iTV’s status as a media company, however dishonestly, they would have a powerful weapon at their disposal should they ever need it.

Over the past few years, strange changes have been made to iTV’s description of itself in its annual reports. The 2021 report said — accurately — that iTV was now just “a holding company principally engaged in non-financial business”. But in 2022 the description was changed to say iTV was a “television media” company even though this had not been true for 15 years. In 2023 it changed again to “advertising media and returns from investments”. No credible explanation has been provided for these changes.

iTV’s latest annual general meeting was held on April 26, 2023. A couple of days beforehand, Nick Sangsirinavin, an election candidate for Bhumjai Thai who had previously been affiliated with Future Forward, posted a message on social media saying any politicians holding iTV shares should attend the AGM and also inform the Election Commission. He added that a party leader, whom he did not name, had 42,000 shares.

Nick had previously held iTV shares too, but transferred them to a colleague, Panuwat Kwanyuen, before registering as an election candidate. He had clearly discovered that Pita also owned shares, and was probably the initial source of the information at the centre of the plot.

In his capacity as a new iTV shareholder, Nick’s colleague Panuwat attended the AGM on April 6 and asked an odd question — “Does iTV still operate media businesses?”

According to a video of the meeting that was later uncovered, executive director Kim Siritaweechai replied: “As of now, the firm doesn’t do anything. It has to wait for the legal case to end.”

It’s clear Panuwat’s question was intended to elicit a reply that could help incriminate Pita. But he didn’t get the answer he was hoping for. Indeed, Kim explicitly confirmed iTV did not operate any media businesses any more.

But when the official minutes of the AGM were published, Kim’s reply had been altered to say: “Currently, iTV still operates in accordance with the company’s objectives, and submitted financial statements and corporate income tax as normal.”

This was the opposite of what he had actually said. Yet the minutes were signed off by Kim.

On May 10, four days before the general election, serial petitioner and Palang Pracharath Party election candidate Ruangkrai Leekitwattana submitted a complaint to the Election Commission claiming Pita was not eligible to be an MP because of his shareholding in iTV. As part of his petition he included iTV’s description of itself as being involved in media in its 2022 and 2023 annual reports, plus the doctored minutes of the AGM.

On June 9, the Election Commission threw out Ruangkrai’s petition, plus other petitions accusing Move Forward candidates of lèse majesté because they supported reform of Article 112. The Commission rejected them on a technicality because the petitions had been filed too late, after the candidates had already been approved.

But this was not the reprieve it appeared to be — far from it. In a sign that a coordinated conspiracy was under way at the behest of the palace, the Election Commission took the extremely unusual step of announcing that even though the petitions had been thrown out, it had seen enough evidence to suspect that Pita had applied to be an MP candidate in the election despite knowing he was not eligible because of his holding of media shares. The commissioners said they would investigate the matter and take appropriate action.

The conspiracy was proceeding smoothly until excellent investigative work by former iTV reporter Thapanee Eadsrichai blew a major hole in it. She managed to find a whistleblower at iTV to give her a video of the AGM. Shown on Channel 3 late in the evening on June 11, the footage clearly showed that the official minutes were inaccurate.

In a news conference the following day, Move Forward secretary-general Chaitawat Tulaton openly accused the party’s opponents of a conspiracy to bring down Pita using falsified evidence.

“It is unlikely that the alteration of the minutes was an accidental mistake or normal practice in preparing meeting reports,” he said. “When the public becomes aware of this, can it be understood that this was an intentional change to align with various documents that were subsequently altered?”

Saksith Saiyasombut provided a good summary of the shenanigans for CNA:

The biggest shareholder in iTV, with a controlling stake of 52.92 percent, is Intouch Holdings, which was previously Thaksin’s conglomerate Shin Corp before he sold his 49.6 percent stake to nominees of Singapore sovereign wealth fund Temasek in 2006. In 2021, Gulf Energy Development massively increased its stake and became the major shareholder in InTopuch. The founder and CEO of Gulf is Sarath Ratanavadi, officially Thailand’s fourth richest person (although the rankings don’t include the royals) who has a 35 percent stake in the company.

Sarath has links with Vajiralongkorn and is an old friend of Bhumjai Thai leader Anutin Charnvirakul. Anutin too has cultivated close links with the palace and has accompanied Vajiralongkon on shopping trips abroad.

Anutin and Palang Pracharat leader Prawit scrambled to distance themselves from the conspiracy, even though one of the key players in the plot, Nick Sangsirinavin, was a Bhumjai Thai election candidate and the mad petitioner Ruangkrai Leekitwattana was a candidate for Palang Pracharath.

“Bhumjai Thai will not waste time on such things because we don’t punch anyone below the belt,” Anutin insisted. “I hereby affirm that I and Sarath have been friends for 40 years or so. Forming a coalition government has nothing to do with my friendship with someone. Please do not mix up everything.”

But Sarath certainly had an incentive to keep Move Forward out of power. The party’s plans to tackle monopolies, promote more competition and reduce power costs would directly impact Gulf Energy. Move Forward had pledged to liberalise the power industry by allowing the public to buy electricity directly from producers, and also plans to renegotiate concessions. Gulf Energy gets most of its income from long-term contracts with the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand.

Following the revelations that the minutes of the meeting had been falsified, Intouch ordered iTV to conduct a thorough investigation.

The executive director and chairman of Intouch is Kim Siritaweechai. The executive director of iTV is also Kim Siritaweechai. The person who chaired the AGM, answered the question about whether iTV had any media operations, and then signed off on a falsified set of minutes was… Kim Siritaweechai. So, absurdly, Kim was ordering himself to investigate why he signed off on a bogus document, and then report back to himself with his findings.

Whether or not Bhumjai Thai or Palang Pracharath were involved, clearly somebody more senior than Kim Siritaweechai intervened after his initial answer at the AGM to get the minutes of the meeting falsified. So clearly some very powerful people were pulling the strings in the plot. All the evidence points back to the palace.

On June 15, iTV issued a statement intended to clarify the whole debacle. They improbably claimed that the reason for the discrepancy between Kim’s actual comments and the minutes of the AGM was because the minutes were just intended to be a summary rather than a verbatim account. They said the document was not intended to imply that iTV was still a media business. In fact its sole sources of revenue are investments and interest.

It was a clear confirmation directly from iTV that it should not be considered a media company.

In any sane democracy this would have been the end of the matter. Not in Thailand.

Despite iTV stating unequivocally that it not a media company and has no immediate prospect of becoming one again, the super-sleuths of the Election Commission decided to plough on with their so-called investigation.

All the Election Commission’s crack team of investigators had to do was conduct a cursory examination of iTV’s revenue streams, read the company’s explicit confirmation that is is not currently involved in media operations, and draw the obvious conclusion that iTV is not currently a media company and nor has it been since 2007. Even the incompetent dotards at the Election Commission could surely have managed this in a couple of days of work and exonerated Pita.

Instead, their eventual decision, and the timing of announcing it, were designed to inflict maximum damage on Move Forward.

Parliament was scheduled to vote on who would become prime minister on July 13.

Although Move Forward had built an eight-party coalition that controlled 312 of the 500 seats in the lower house of parliament, Pita faced a daunting challenge in his bid to become premier because under the anti-democratic 2017 constitution drawn up by the junta, the 250 unelected senators handpicked by the generals also had the right to vote in the selection of the prime minister. The vast majority of them were implacably opposed to Move Forward and were determined to stop Pita.

According to a Nikkei Asia article:

An elder statesman told Nikkei he was doubtful that Pita could win enough votes from the military-appointed senate to take office. A senior courtier close to King Maha Vajiralongkorn, the country's ultimate power, also said the idea of a Move Forward government was “nuts” and predicted a long caretaker period under Prayuth.

With his coalition able to muster 312 votes, Pita needed 64 votes from the 250 senators to become prime minister. The only real hope for Move Forward was to stress its strength of support from millions of Thais, in the hope that some senators would balk at defying the democratic wishes of the electorate.

The party held a rally on July 9 in central Bangkok, with a large crowd packing the street and surrounding skywalks despite heavy rain.

Pita also tweeted a speech on July 11 in which he called for support from the Senate.

“The vote for prime minister isn’t about choosing Pita or the Move Forward party,” he said. “It’s about reaffirming that Thailand must move forward in line with the democratic system.”

But on July 12, just a day before the parliamentary vote, the deep state struck a decisive double punch against Pita and Move Forward that was more brutal than even the most pessimistic observers anticipated.

First, after weeks of pretending to scrutinise the issue, the commission chose to announce on the eve of the premiership vote that it had asked the Constitutional Court to rule on whether Pita should be disqualified as an MP because he held shares in a media company in violation of the constitution. The six election commissioners also requested that the court suspend Pita as an MP pending its ruling on the matter.

It was a clearly partisan intervention. The decision itself was ludicrous, because the evidence was clear that iTV was no longer a media company. But also the speed of the Election Commission investigation, the announcement on the eve of the vote in parliament, and the recommendation to suspend Pita, did not follow the same pattern as investigations into allies of the regime.

As pointed out on Facebook by Future Forward co-founder Piyabutr, in 2017/8 ago the election commissioners took 386 days to investigate a case against foreign minister Don Pramudwinai over questionable shareholdings owned by his wife, before requesting a ruling from the Constitutional Court on his eligibility for office. The court then took 70 days to decide to hear the case without suspending Don from office during the ongoing investigation.

In 2018/9 the Election Commission took 355 days to investigate a case against four ministers in the junta government accused of holding shares in companies that received government concessions, and the Constitutional Court then took 75 days to decide to hear the case without suspending the ministers during the investigation.

The commission took just 51 days to investigate Thanathorn, and the court took only seven days to decide to hear the case, ordering his suspension as an MP during their deliberations.

Pita’s case was processed even faster, Piyabutr noted — the Election Commission came up with its decision to refer him to the Constitutional Court, and recommend his suspension, in just 32 days.

A few hours after the Election Commission announcement, the Constitutional Court delivered the second shattering blow, announcing it had accepted an absurd petition seeking a ruling on whether Move Forward’s policy of seeking reform of Article 112 amounted to an attempt to overthrow the constitutionally enshrined system of so-called “democracy with the king as head of state”. In effect, judges were saying that the question of whether Move Forward was guilty of treason was worthy of consideration.

The timing of these announcements was no coincidence. They were clearly intended to snuff out any faint possibility that enough senators would vote for Pita to enable him to become prime minister.

“In the short run, this development increases the likelihood that Pita will not have enough support in parliament,” said Napon Jatusripitak, a visiting fellow at ISEAS in Singapore. “In the long run, it raises concerns about the erosion of democratic principles and the potential for widespread protests.”

An editorial in the usually staunchly pro-establishment Bangkok Post was scathing:

The latest development shows attempts by the conservative side to maintain power, despite its massive election loss. In doing so, they simply fail to respect voters’ wishes and have used every tactic, some egregious, to maintain the status quo.

Some senators who had pledged support for Mr Pita reportedly complained of intimidation and blackmail. Others confirm that there are bribe offers so that they would change their mind. Scandals and rumours that riddle the Upper House do not bode well for the institution and for democracy.

What is going on is bad for democracy and the country.

Meanwhile, activists held protests in several parts of the country. Some adopted a new symbol of dissent, placing stylised Thai letters representing the acronym for the Election Commission in a layout that resembled a penis and testicles.

V. Democracy denied

“This is a bit rushed, one day before the PM vote, it shouldn't have happened,” Pita told reporters after the devastating announcements of July 12.

Regardless of the merits of either case — the alleged media shareholding or the alleged treason — it gave wavering senators the cover they needed to abstain, which was equivalent to a vote against Pita as he needed 375 positive votes to win the premiership. Senators could simply say they did not feel comfortable voting for Pita with so much legal uncertainty hanging over him and his party. His bid for the premiership was now doomed.

Sure enough, on July 13, Pita fell well short of the voters he needed. He received just 324 votes, including only 13 senators, so fell 51 votes short. There were 199 abstentions, and 182 votes against him. Despite earning generous salaries for doing very little most of the time, 44 people didn’t even show up to vote.

“The powerful conservative forces arrayed against Pita have made some last-minute power plays,” said Chulalongkorn University’s Tahitian. “All the old elites see Pita and his Move Forward party as an existential threat.”

This graphic by Reuters illustrates the voting:

“I accept it but I'm not giving up,” Pita told reporters after the vote. “I will not surrender and will use this time to garner more support.”

Another vote on whether Pita should get the premiership was scheduled for July 19. Move Forward hoped to persuade enough senators to change their minds to win, although it seemed an impossible task.

But a vote was never held. Several conservative MPs and senators objected that renominating Pita breached parliamentary meeting regulation 41, which prohibits the resubmission of a failed motion during the same parliamentary session unless new circumstances have emerged. Rather than make a ruling on the issue, which was a key responsibility of his job, house speaker Wan Muhamad Noor Matha instead opened the issue up for debate by members of parliament and senators, and then called a vote on whether the nomination should be allowed.

In the joint sitting, 394 parliamentarians, most of them unelected senators, voted against Pita's renomination, 312 voted to support it, eight abstained and one did not exercise the right to vote.

During the debate, the Constitutional Court announced it had accepted the Election Commission’s request for a ruling on whether he should be disqualified as a member of parliament because of his shareholding in iTV, and ordered Pita to be suspended until they had ruled on the merits of the case. Once again, the timing of the announcement, on the day Pita was trying for a second time to get enough votes to become prime minister, was no coincidence.

Upon hearing the news, Pita began leaving the chamber, but came back to his seat when his colleague Wiroj pointed out that he should wait for an official letter. When that arrived during the afternoon, Pita told Wan Noor:

I’d like to take this opportunity to say goodbye to the parliament president until we meet again. I would like fellow members to use the parliament to take care of the people. I think that Thailand is different since May 14. If people have won halfway, the other half has yet to come, and even if I haven’t done my duty I ask all fellow members to jointly take care of the people. Thank you very much, Mr President.

He took off his MP identification card from his jacket, placed it on the desk in front of him, and walked out of the chamber.

In theory, Pita still had a chance of becoming prime minister despite being suspended because a Thai premier does not have to be a member of parliament. But in practice, it was never going to happen. The deep state had already made sure of that.

Numerous legal experts, including former constitution drafter Bowornsak Uwanno, questioned parliament’s decision to block Pita’s renomination. They said the constitution was paramount over parliamentary regulations, and the constitution allowed a candidate for the premiership to be nominated more than once.

Bowornsak is a royalist conservative, but he said he was disappointed with those who had blocked a second vote, writing on Facebook: “Although you are in the opposition, you should be aware of when to do away with being in the opposition to do the right thing.”

The next vote was scheduled for July 27. Move Forward had promised that if they were unable to secure the premiership for Pita after two attempts, they would make way and allow their coalition partner Pheu Thai to try to form a government. On July 21 they announced that they would not seek to renominate Pita.

“It is clear that conservative forces — from politicians, business monopolies and institutions — they will not let Move Forward become government,” party secretary-general Chaithawat told a news conference.

But no vote was held on July 27. Move Forward and some independent academics had petitioned the parliamentary ombudsman to seek a Constitutional Court ruling on whether Wan Noor had breached the charter by allowing parliament to block Pita’s renomination on July 19. Meanwhile, 115 law lecturers from 19 universities issued a joint statement saying Wan Noor’s actions had been unconstitutional. On July 24, the Office of the Ombudsman said any further vote should be postponed until a ruling had been made on the issue.

On August 2, Pheu Thai announced it was leaving the coalition with Move Forward and would seek to build a government without its former ally, to secure enough votes from its candidate for the premiership, Srettha Thavisin. Even before the announcement, Pheu Thai had been holding talks with royalist and military parties that it had previously promised to shun.

Move Forward, the party that had won the most votes and most seats in the election had been frozen out of being part of the next government. The royalist elite had won.

The next vote was tentatively scheduled for August 4, but was cancelled when the Constitutional Court announced it would consider the petition on whether preventing Pita being renominated breached the charter. The court said it would issue a preliminary ruling on August 16.

This meant that three months after the May 14 election, Thailand would still not have a prime minister. The kingdom remained trapped in political limbo.

The Constitutional Court’s ruling on August 16 was another clearly partisan decision. The judges made the absurd claim that because the petition had been submitted by the Office of the Ombudsman — which was the correct procedure — it was not valid because petitions must be submitted by somebody whose rights and freedom had been directly affected.

“None of the petitioners are the persons whose right and freedom were abused directly,” the court said. “As a result, the court unanimously rejects the petition.”

This clumsy chicanery enabled the judges of the Constitutional Court to evade having to declare that the actions of Wan Noor and the MPs and senators who voted to block Pita’s renomination were unconstitutional, which would have been an awkward setback for those in the deep state — including the judges themselves — who were conspiring to sabotage Move Forward.

The ruling allowed another vote on a prime minister to finally be held. On August 22, more than three-and-a-half months after the general election, Srettha Thavisin became Thailand’s new premier, with 482 votes from the 727 politicians. Move Forward declined to vote for him, but Pheu Thai’s old enemies in the military parties Palang Pracharat and United Thai Nation gave him their support in return for promises of cabinet positions.

On September 15, 2023, Pita resigned as leader of Move Forward, with Chaithawat taking his place. He explained that Move Forward could not be an effective opposition in parliament with a suspended leader at the helm:

The opposition leader is like the prow of a ship that directs the opposition’s performance in parliament, performs checks and balances on the government and pushes for agendas of change that are missing from the government’s policy.

Thailand’s electorate had voted for change but instead had been given another corrupt and unprincipled coalition. The democratic wishes of the people, who had voted overwhelmingly for genuine reforms and an end to military meddling in politics, had been disregarded.

On January 24 this year, after more than seven months of deliberations, the nine mouldering old men of Thailand’s Constitutional Court finally issued a ruling that they could easily have come up with within days of taking on the case on July 19 last year. They announced that Pita had been elected legitimately and can resume his political career.

Move Forward posted a video on TikTok with Pita saying he was looking forward to returning to work.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

But while the Constitutional Court’s decision may have seemed a rare moment of sanity from the decrepit judges, in reality it was nothing of the sort.

Firstly, they didn’t need to ban Pita from politics. By suspending him at a crucial juncture in the selection of Thailand’s next prime minister, and keeping him out of parliament for months, they had already achieved their goal. They had prevented him from becoming premier and ensured Move Forward would not be part of the government.

Given the weakness of the case against him, a punitive ruling against Pita would just have led to more criticism of the court, and possibly renewed mass protests. By ruling in his favour, the judges could try to give the false impression that they were fair and impartial.

But more importantly, the judges also knew that they no longer needed to strip Pita of his MP status, because they had a much more effective weapon ready which could devastate Move Forward. A week after exonerating Pita, they unleashed it.

The second part of this series, discussing how the lèse majesté law was weaponised to target democracy activists and keep Move Forward out of power, will be published soon. To receive the article and all Secret Siam newsletters you can sign up here:

Thank you Andrew. As someone who has followed the goings on in Thailand for year from my home in Malaysia yours is a fabulous source to follow.

Thank you Andrew. Always a pleasure to read your articles.

I sincerely hope all your articles are available in Thai script so that the Thai folks can be aware as we are.