A history of modern Thailand in five royal dogs

The stories of Jarlet, Tongdaeng, Foo Foo, Luk Mee and Princess Perfume

The latest edition of Secret Siam focuses on some of the most famous members of the Thai royal family — their dogs. The post is for paying subscribers so if you’d like to read it and haven’t signed up yet, you can do that here.

Since the reign of King Rama VI a century ago, most of the leading Thai royals have been dog lovers, and the stories of palace mongrels like Jarlet and Tongdaeng, as well as the pampered pedigree pets Foo Foo, Luk Mee and Princess Perfume, shed a surprising amount of light on the personality of their owners, and the monarchy itself. So here is a history of modern Thailand, via the stories of five royal dogs…

Jarlet — ย่าเหล

Jarlet didn’t get a great start in life. He was a mongrel, born in jail. But a few weeks after his birth in 1908 a very important visitor came to the grim prison building in Nakhon Pathom where he lived, and everything changed.

Prince Vajiravudh was born in 1881, in a palace in Bangkok rather than a provincial prison. When he was 12 he was sent to continue his education in England, and two years later he was unexpectedly named heir to the throne of Siam by his father King Chulalongkorn after his half-brother Vajirhunis died of typhus.

Although Siam was never officially colonised, it was regarded by the British as firmly in their sphere of influence, an offshoot of the empire where the monarchy had been allowed to remain in power in return for allowing unrestricted trade and extraterritorial jurisdiction. The British government was adamant that future monarchs of Siam should have an English aristocratic education, which they thought would ensure the Thai royals would align with their imperial interests. So they insisted that Vajiravudh should attend the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, then spend a brief spell as an officer in an English regiment, the Durham Light Infantry, before studying law and history at Christ Church College, Oxford.

Vajiravudh became fascinated by literature and drama, and believed himself to be an accomplished poet and playwright. He was a great admirer of the works of William Shakespeare and the comic operas of W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, but his favourite play in the world was one now long forgotten — a one-act drama called My Friend Jarlet by English authors Arnold Golsworthy and E.B. Norman. It’s a strange tale, set during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, about a man called Emile Jarlet who sacrifices his life to save his closest friend Paul, who is also the lover of Jarlet’s daughter Marie Leroux.

Vajiravudh was deeply moved by the play’s themes of male friendship and sacrifice, and during his time as a student in England he wrote a Thai translation which he called มิตรแท้, or A Friend Indeed. He staged the play for his father Chulalongkorn during a visit by the king to Geneva in 1897. Vajiravudh played the female character Marie. In this era, where elite schools were segregated by sex and universities like Oxford admitted only men, it was not unusual for males to take female roles in dramatic productions.

Crown Prince Vajiravudh returned to Siam in 1903, when he was 22 years old. He came home with a secret — he was gay, in an era when this was something that had to be concealed and denied. On his return to Thailand he began surrounding himself with an exclusively male royal court, bringing young men he liked into his entourage as pages and courtiers, and later appointing them to high-ranking official positions. His preference for surrounding himself with male “friends” may be another reason he was so obsessed with My Friend Jarlet. He felt lonely and isolated, and believed that intense devoted friendship among men was the most noble form of love — a view also common among the English aristocracy during the Victorian era.

As Craig Reynolds has argued in a review of Chanan Yothong’s groundbreaking book Men of the inner palace during the sixth reign:

Vajiravudh inherited the throne from a spectacularly successful father, who had extensive kin, perhaps 500 of them. Yet Vajiravudh, despite his high status as the offspring of one of the three chief queens, felt alone. Because he had spent nine years abroad, followed by eight years back in Siam in the shadow of his uncles and other senior members of the family, and possibly because of his personality and preoccupations with drama, literature, and the arts, he had few allies in the family...

The patronage of gifts and promotion to rank he granted … through the years created not only a distinctive group of men loyal to him, but also an affluent coterie of refined gentlemen who shared his tastes and values.

Vajiravudh struggled with the pressures of being a future king, and of reconciling his royal role with his sexuality. His decision to surround himself with an exclusively male entourage to serve and pleasure him scandalised the nobility, and to give himself some distance from palace intrigues and gossip in Bangkok he established a residence in Nakhon Pathom to the west of the capital. Construction of the Sanam Chandra Palace complex began in 1907.

In 1908, Vajiravudh went on an inspection visit to Nakhon Pathom prison, not far from Sanam Chandra. During his tour of the jail he saw two adorable puppies with mostly white fluffy fur apart from a few dark patches. The crown prince decided to adopt the dogs and their mother. He named the two puppies Jarlet and Paul.

Paul died soon afterwards, but Jarlet became a constant companion of the king, following him everywhere, lying at his feet as he wrote or ate, and barking at intruders. Vajiravudh regarded him as a loyal and beloved friend.

In 1910, Chulalongkorn died at the age of 57, and Vajiravudh became King Rama VI of Siam much earlier than he had hoped. His reign is widely regarded as a disaster. His promotion of male favourites to senior positions in the government and royal court infuriated the aristocracy who were excluded from these roles. He further angered the military by creating a new armed force, the Wild Tigers, under his direct command, and by socialising with these soldiers while shunning the established army. He spent so lavishly on ceremonies, his personal army and his male friends that the kingdom’s finances were drained almost to bankruptcy.

Jarlet was also extremely unpopular. The dog was showered with treats and luxuries, pampered by royal pages, and had a habit of biting visitors to the palace. For many of those in the nobility and military who resented Vajiravudh’s elevation of his chosen companions to power at their expense, the dog symbolised everything they hated about his reign — a prison-born mongrel was being treated like an honoured aristocrat and given medals declaring him a member of the royal guards.

In 1912, a group of military officers, including some royal bodyguards, began conspiring to overthrow the king by surrounding him at a ceremony on April 1 and demanding that he step down. According to later charges against the plotters, which they denied, they also intended to assassinate Vajiravudh if he refused to accept their demands. Details of the plot were leaked on February 29 by one of the officers involved, and in May, 91 people were found guilty of taking part in the conspiracy. Three were sentenced to death, 20 to life imprisonment, and the rest were given long jail terms, although shortly afterwards Vajiravudh reduced all the sentences, and all the prisoners were released twelve years later.

The abortive coup left Rama VI feeling more isolated than ever. As Reynolds says:

Feeling vulnerable and fearing rebellion, Vajiravudh ventured into the more public areas of the palace only when duty requiredand sought refuge from danger in the inner palace or in his private quarters… the inner palace was like a fortified bunker where, surrounded by those he loved and trusted, he felt safe from his enemies.

In his inner sanctum, Vajiravudh was looked after by his male attendants as past kings had been served by women, and by his side too was the faithful Jarlet.

But in 1913, a year after the foiled rebellion, Jarlet was assassinated. His body was found near the Grand Palace, shot several times — just as the character in the play had been. In royal histories, blame for the killing of Jarlet is usually pinned on palace servants who were angry about being bitten or barked at, but this is unlikely. The use of a gun makes it more probable that somebody in the military or nobility killed Jarlet, as a message to Vajiravudh. It was another sign of the simmering discontent in the kingdom.

Vajiravudh was heartbroken by the loss of his canine friend. Jarlet was given an elaborate funeral, with attendants dressed in animal costumes accompanying the coffin. Vajiravudh commissioned the Italian architect Ercole Manfredi, who he’d given a position in the Ministry of the Royal Household, to create a statue of Jarlet which was installed on a large stone plinth at Sanam Chandra Palace in Nakhon Pathom. In memory of his companion, the king composed a long poem, which was also displayed on the plinth, proclaiming Jarlet to be a truly loyal friend.

The statue was erected in 1914 in front of the Charlie Mongkol Asana Mansion which had been built in 1908 according to a design intended to emulate a French chateau from My Friend Jarlet. In 1916 another building was added to the complex, the Marie Rajratta Banlang Mansion. Charlie and Marie are both characters in the play.

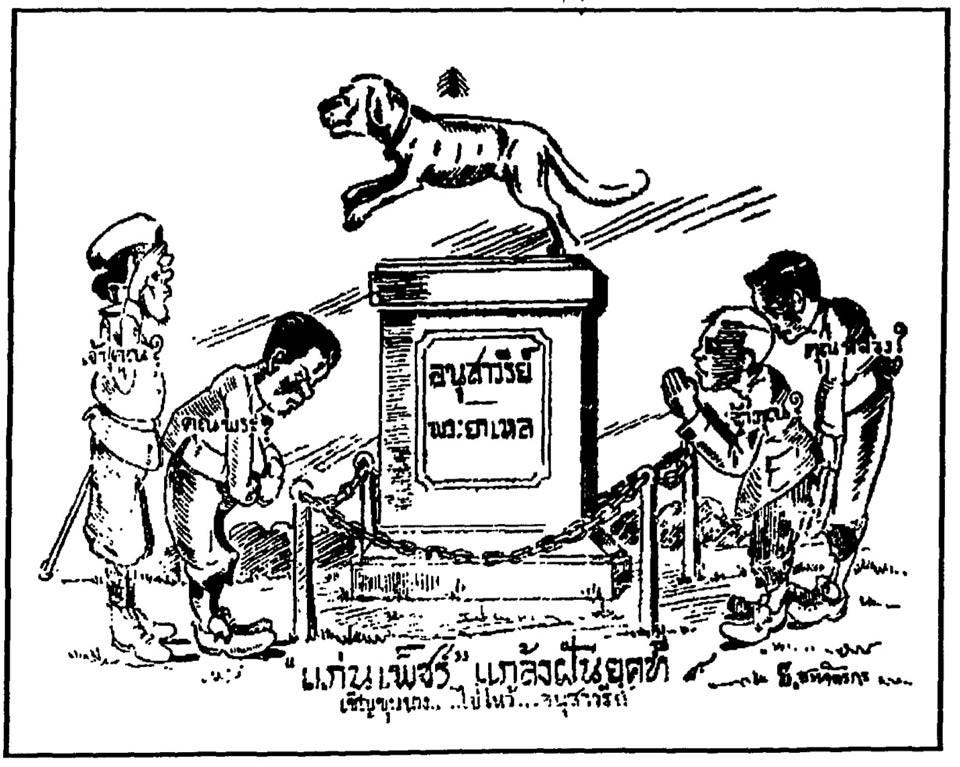

Vajiravudh became increasingly unwell as his reign progressed, and in the kingdom, discontent grew. Newspapers mocked and criticised the monarch with a boldness unthinkable in the modern Thai media. Among the boldest of all was journalist and cartoonist Sem Sumanan, who was editor of the newspaper Bangkok Kanmuang before joining another publication, Kro Lek, in 1924. Sem mercilessly attacked Vajiravudh and the excesses of the Siamese nobility, and in December 1924 he produced a cartoon ridiculing the veneration of Jarlet. The symbol above the dog is intended to depict rays of light, a coded sign in Sem’s cartoons that denoted royalty.

But while the statue may have been preposterous, Vajiravudh’s grief over his dog was real. He kept several other pets in the final years of his reign, until his death in 1925, but none were ever as special to Vajiravudh as his friend Jarlet, whose statue still stands today at the palace in Nakhon Pathom, not far from the prison where he was born.

Tongdaeng — ทองแดง

Tongdaeng began her life in even less auspicious circumstances than Jarlet — she was one of seven puppies born to a stray street dog in an alleyway under the Ramintra Expressway, not far from the Golden Place Rama 9 supermarket, towards midnight on November 7, 1998. She also rose even higher than her predecessor, becoming the most famous and revered dog in the history of Thailand.

King Bhumibol Adulyadej, a monarch who was loved by many Thais much more than he deserved, visited the area six weeks earlier on September 29 to consecrate the foundation stone of the new Medical Development Clinic. According to Bhumibol’s later account of what happened, when Bangkok municipal officials were preparing the area for the visit, they removed four street dogs that were looked after by locals. Bhumibol said that when people in the neighbourhood complained to the palace about the disappearance of the dogs, he sent an order that they should be returned to the community. The story may be embellished or untrue — it conforms suspiciously neatly to a persistent theme of palace propaganda in which the monarch is portrayed as always receptive to solving the problems and complaints of the poor, and always ready to their side against heartless officials — but according to Bhumibol’s tale, when the four strays were brought back, another two street dogs were with them. One of them, a “skinny and mangy” dog called Daeng, took refuge in an alley beside the clinic and refused to leave. After she gave birth to her litter of six female puppies and one male on November 7, locals and building workers brought a cardboard box for them to sleep in, old newspapers and towels for bedding, and milk for the puppies.