A history of modern Thailand in five royal dogs

The stories of Jarlet, Tongdaeng, Fufu, Luk Mee and Princess Perfume

The latest edition of Secret Siam focuses on some of the most famous members of the Thai royal family — their dogs. The post is too long to send via email, so below are the stories of Jarlet and Tongdaeng, and paying subscribers can view the rest if the article on the Secret Siam website. If you’d like to read the full article and haven’t subscribed yet, you can do that here:

Since the reign of King Rama VI a century ago, most of the leading Thai royals have been dog lovers, and the stories of palace mongrels like Jarlet and Tongdaeng, or the pampered pedigree pets Fufu, Luk Mee and Princess Perfume, shed a surprising amount of light on the personality of their owners, and the monarchy itself. So here is a history of modern Thailand, via the stories of five royal dogs…

Jarlet — ย่าเหล

Jarlet didn’t get a great start in life. He was a mongrel, born in jail. But a few weeks after his birth in 1908 a very important visitor came to the grim prison building in Nakhon Pathom where he lived, and everything changed.

Prince Vajiravudh was born in 1881, in a palace in Bangkok rather than a provincial prison. When he was 12 he was sent to continue his education in England, and two years later he was unexpectedly named heir to the throne of Siam by his father King Chulalongkorn after his half-brother Vajirhunis died of typhus.

Although Siam was never officially colonised, it was regarded by the British as firmly in their sphere of influence, an offshoot of the empire where the monarchy had been allowed to remain in power in return for allowing unrestricted trade and extraterritorial jurisdiction. The British government was adamant that future monarchs of Siam should have an English aristocratic education, which they thought would ensure the Thai royals would align with their imperial interests. So they insisted that Vajiravudh should attend the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, then spend a brief spell as an officer in an English regiment, the Durham Light Infantry, before studying law and history at Christ Church College, Oxford.

Vajiravudh became fascinated by literature and drama, and believed himself to be an accomplished poet and playwright. He was a great admirer of the works of William Shakespeare and the comic operas of W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, but his favourite play in the world was one now long forgotten — a one-act drama called My Friend Jarlet by English authors Arnold Golsworthy and E.B. Norman. It’s a strange tale, set during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, about a man called Emile Jarlet who sacrifices his life to save his closest friend Paul, who is also the lover of Jarlet’s daughter Marie Leroux.

Vajiravudh was deeply moved by the play’s themes of male friendship and sacrifice, and during his time as a student in England he wrote a Thai translation which he called มิตรแท้, or A Friend Indeed. He staged the play for his father Chulalongkorn during a visit by the king to Geneva in 1897. Vajiravudh played the female character Marie. He performed the same role during a staging of the play in St Petersburg, Russia, in 1901. In this era, where elite schools were segregated by sex and universities like Oxford admitted only men, it was not unusual for males to take female roles in dramatic productions. The images below show Vajiravudh as Marie in Geneva (left) and St Petersburg (right).

Crown Prince Vajiravudh returned to Siam in 1903, when he was 22 years old. He came home with a secret — he was gay, in an era when this was something that had to be concealed and denied. On his return to Thailand he began surrounding himself with an exclusively male royal court, bringing young men he liked into his entourage as pages and courtiers, and later appointing them to high-ranking official positions. His preference for surrounding himself with male “friends” may be another reason he was so obsessed with My Friend Jarlet. He felt lonely and isolated, and believed that intense devoted friendship among men was the most noble form of love — a view also common among the English aristocracy during the Victorian era.

As Craig Reynolds has argued in a review of Chanan Yothong’s groundbreaking book Men of the inner palace during the sixth reign:

Vajiravudh inherited the throne from a spectacularly successful father, who had extensive kin, perhaps 500 of them. Yet Vajiravudh, despite his high status as the offspring of one of the three chief queens, felt alone. Because he had spent nine years abroad, followed by eight years back in Siam in the shadow of his uncles and other senior members of the family, and possibly because of his personality and preoccupations with drama, literature, and the arts, he had few allies in the family...

The patronage of gifts and promotion to rank he granted … through the years created not only a distinctive group of men loyal to him, but also an affluent coterie of refined gentlemen who shared his tastes and values.

Vajiravudh struggled with the pressures of being a future king, and of reconciling his royal role with his sexuality. His decision to surround himself with an exclusively male entourage to serve and pleasure him scandalised the nobility, and to give himself some distance from palace intrigues and gossip in Bangkok he established a residence in Nakhon Pathom to the west of the capital. Construction of the Sanam Chandra Palace complex began in 1907.

In 1908, Vajiravudh went on an inspection visit to Nakhon Pathom prison, not far from Sanam Chandra. During his tour of the jail he saw two adorable puppies with mostly white fluffy fur apart from a few dark patches. The crown prince decided to adopt the dogs and their mother. He named the two puppies Jarlet and Paul.

Paul died soon afterwards, but Jarlet became a constant companion of the king, following him everywhere, lying at his feet as he wrote or ate, and barking at intruders. Vajiravudh regarded him as a loyal and beloved friend.

In 1910, Chulalongkorn died at the age of 57, and Vajiravudh became King Rama VI of Siam much earlier than he had hoped. His reign is widely regarded as a disaster. His promotion of male favourites to senior positions in the government and royal court infuriated the aristocracy who were excluded from these roles. He further angered the military by creating a new armed force, the Wild Tigers, under his direct command, and by socialising with these soldiers while shunning the established army. He spent so lavishly on ceremonies, his personal army and his male friends that the kingdom’s finances were drained almost to bankruptcy.

Jarlet was also extremely unpopular. The dog was showered with treats and luxuries, pampered by royal pages, and had a habit of biting visitors to the palace. For many of those in the nobility and military who resented Vajiravudh’s elevation of his chosen companions to power at their expense, the dog symbolised everything they hated about his reign — a prison-born mongrel was being treated like an honoured aristocrat and given medals declaring him a member of the royal guards.

In 1912, a group of military officers, including some royal bodyguards, began conspiring to overthrow the king by surrounding him at a ceremony on April 1 and demanding that he step down. According to later charges against the plotters, which they denied, they also intended to assassinate Vajiravudh if he refused to accept their demands. Details of the plot were leaked on February 29 by one of the officers involved, and in May, 91 people were found guilty of taking part in the conspiracy. Three were sentenced to death, 20 to life imprisonment, and the rest were given long jail terms, although shortly afterwards Vajiravudh reduced all the sentences, and all the prisoners were released twelve years later.

The abortive coup left Rama VI feeling more isolated than ever. As Reynolds says:

Feeling vulnerable and fearing rebellion, Vajiravudh ventured into the more public areas of the palace only when duty requiredand sought refuge from danger in the inner palace or in his private quarters… the inner palace was like a fortified bunker where, surrounded by those he loved and trusted, he felt safe from his enemies.

In his inner sanctum, Vajiravudh was looked after by his male attendants as past kings had been served by women, and by his side too was the faithful Jarlet.

But in 1913, a year after the foiled rebellion, Jarlet was assassinated. His body was found near the Grand Palace, shot several times — just as the character in the play had been. In royal histories, blame for the killing of Jarlet is usually pinned on palace servants who were angry about being bitten or barked at, but this is unlikely. The use of a gun makes it more probable that somebody in the military or nobility killed Jarlet, as a message to Vajiravudh. It was another sign of the simmering discontent in the kingdom.

Vajiravudh was heartbroken by the loss of his canine friend. Jarlet was given an elaborate funeral, with attendants dressed in animal costumes accompanying the coffin. Vajiravudh commissioned the Italian architect Ercole Manfredi, who he’d given a position in the Ministry of the Royal Household, to create a statue of Jarlet which was installed on a large stone plinth at Sanam Chandra Palace in Nakhon Pathom. In memory of his companion, the king composed a long poem, which was also displayed on the plinth, proclaiming Jarlet to be a truly loyal friend.

The statue was erected in 1914 in front of the Charlie Mongkol Asana Mansion which had been built in 1908 according to a design intended to emulate a French chateau from My Friend Jarlet. In 1916 another building was added to the complex, the Marie Rajratta Banlang Mansion. Charlie and Marie are both characters in the play.

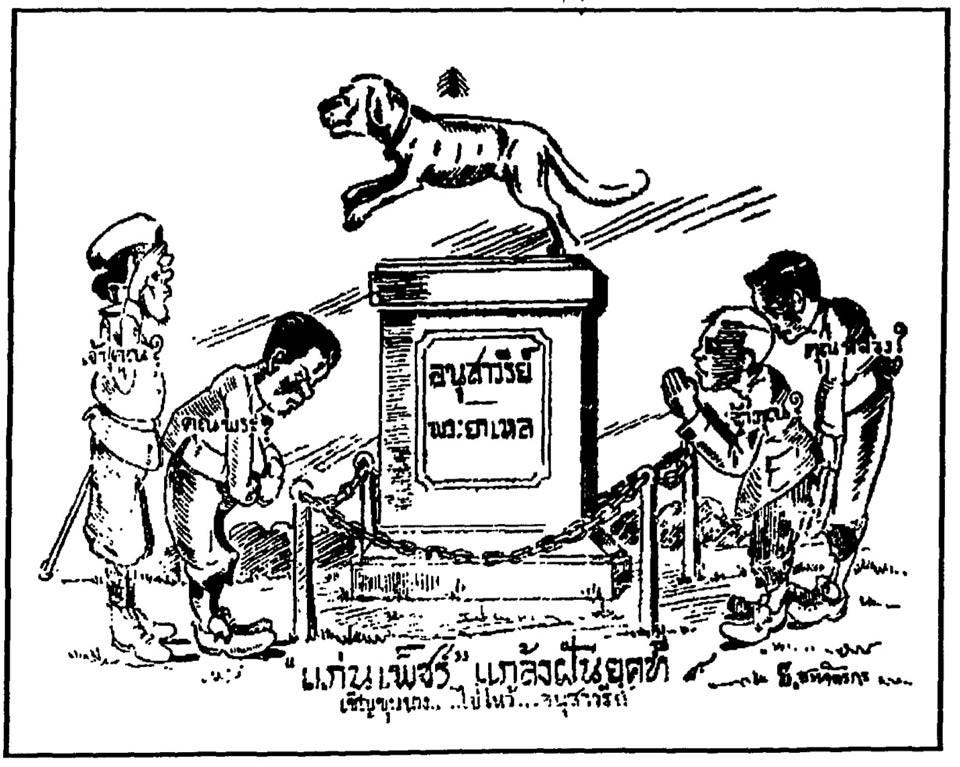

Vajiravudh became increasingly unwell as his reign progressed, and in the kingdom, discontent grew. Newspapers mocked and criticised the monarch with a boldness unthinkable in the modern Thai media. Among the boldest of all was journalist and cartoonist Sem Sumanan, who was editor of the newspaper Bangkok Kanmuang before joining another publication, Kro Lek, in 1924. Sem mercilessly attacked Vajiravudh and the excesses of the Siamese nobility, and in December 1924 he produced a cartoon ridiculing the veneration of Jarlet. The symbol above the dog is intended to depict rays of light, a coded sign in Sem’s cartoons that denoted royalty.

But while the statue may have been preposterous, Vajiravudh’s grief over his dog was real. He kept several other pets in the final years of his reign, until his death in 1925, but none were ever as special to Vajiravudh as his friend Jarlet, whose statue still stands today at the palace in Nakhon Pathom, not far from the prison where he was born.

Tongdaeng — ทองแดง

Tongdaeng began her life in even less auspicious circumstances than Jarlet — she was one of seven puppies born to a stray street dog in an alleyway under the Ramintra Expressway, not far from the Golden Place Rama 9 supermarket, towards midnight on November 7, 1998. She also rose even higher than her predecessor, becoming the most famous and revered dog in the history of Thailand.

King Bhumibol Adulyadej, a monarch who was loved by many Thais much more than he deserved, visited the area six weeks earlier on September 29 to consecrate the foundation stone of the new Medical Development Clinic. According to Bhumibol’s later account of what happened, when Bangkok municipal officials were preparing the area for the visit, they removed four street dogs that were looked after by locals. Bhumibol said that when people in the neighbourhood complained to the palace about the disappearance of the dogs, he sent an order that they should be returned to the community. The story may be embellished or untrue — it conforms suspiciously neatly to a persistent theme of palace propaganda in which the monarch is portrayed as always receptive to solving the problems and complaints of the poor, and always ready to their side against heartless officials — but according to Bhumibol’s tale, when the four strays were brought back, another two street dogs were with them. One of them, a “skinny and mangy” dog called Daeng, took refuge in an alley beside the clinic and refused to leave. After she gave birth to her litter of six female puppies and one male on November 7, locals and building workers brought a cardboard box for them to sleep in, old newspapers and towels for bedding, and milk for the puppies.

Bhumibol said one of the female puppies was presented to him on December 13, 1998, because of her distinctive markings — “the half-necklace on her neck, four white socks, the curled tail, and most important, the white spot on the nose and the tail tip”. He named her Tongdaeng, which means copper. Bhumibol already owned several dogs, and a new royal puppy called Tongdam had been born on November 8, also with white spots on its nose and tail tip. The king thought Tongdam and Tongdaeng could be future mates.

Bhumibol said Tongdaeng “cried all the way” to Chitralada Palace when she was being brought to him:

Perhaps it was because she missed her mother and was lonely because she was so very young. Although the one who brought her gave her some milk and cakes, she did not stop crying.

But when she met the king, she was suddenly at peace:

Strangely enough, once she had been presented to His Majesty, she stopped crying, and crawled to nestle on his lap, as if entrusting her life to his care, and fell fast asleep, free from all worries, loneliness and fear.

A palace photographer captured the moment, with Tongdaeng asleep, and Tongdam climbing onto Bhumibol’s leg. Unusually, the king was almost smiling.

Throughout his reign, palace propaganda had portrayed Bhumibol as a genius, a monarch of immense knowledge and wisdom, and at some point he had started believing it too. He really thought he was smarter than everybody else, and shared random thoughts and eccentric ideas as if they were brilliant insights. Bhumibol became fixated with the idea that Tongdaeng, a typical mongrel soi dog, was descended from Basenji hunting hounds, which originated in Africa. So he decided to mate her with another of his dogs, Tongtae, which he thought had Basenji characteristics too. On September 26, 2000, Tongdaeng gave birth to three female puppies and six males.

Meanwhile, Bhumibol had passed two significant milestones in his life — he marked his sixth cycle 72nd birthday in December 1999, and five months later he overtook Rama I to become the oldest king in Thai history. He had been hoping to retire for many years, but his heir Vajiralongkorn was so clearly unsuitable as a monarch that he felt he had no choice but to keep going. A new constitution, pushed through in 1997 by liberal royalist allies of Bhumibol, was designed to prepare the ground for royal succession by creating stronger institutions so that the monarch’s role would become more symbolic. Approaching the twilight of his life, Bhumibol sought to step back from his royal duties and spend his final years in peace and quiet. He removed himself from Bangkok and went to live in semi-seclusion in the royal resort of Hua Hin, at the seaside palace known as Klai Kangwon — Far from Worries.

Unlike Vajiravudh, who craved companionship throughout his life, Bhumibol was a solitary figure, prone to depression and often cantankerous. As maverick royalist Sulak Sivaraksa told US magazine Fellowship in a 1992 interview:

He’s a very nice man, but he has no friends, and he knows it. People surround him, flatter him, and so on.

Bhumibol had lived separately from his increasingly unbalanced wife Sirikit since the 1980s, and was estranged from three of his four children — Princess Sirindhorn was the only one he was close to. After he decamped to Hua Hin, he became even more isolated. A secret US cable in 2009 observed:

The King's decade-long sojourn in Hua Hin starting in 2000 significantly limited the amount of interaction he had not only with the Queen but also those whom many outsiders (incorrectly) presume spend significant amounts of time with him: Privy Councilors; as well as officials of the office of the Principal Private Secretary, all of whom are Bangkok-based and do not have regular access to the King.

His closest friend and companion was Tongdaeng, and Bhumibol’s main project after moving to Hua Hin was working on a book praising his favourite dog.

The Story of Tongdaeng, published in 2002, was more than just a tribute to Bhumibol’s most beloved pet — it was also a not-very-subtle message to his human subjects. The king praised Tongdaeng as “a respectful dog with proper manners” who was “humble and knows protocol”. She knew her place in the Thai social hierarchy:

When she is with the King, she would always stay lower than him. Even if he pulls her up to embrace her, Tongdaeng would quickly crouch on the floor, her ears down in a respectful manner, as if saying, “I dare not; it’s not proper.”

Back in 1873, King Chulalongkorn had stopped the archaic custom of prostrating to royals, declaring it was an “oppressive and unjust practice”. But during Bhumibol’s reign the custom had resumed, and it was clear from The Story of Tongdaeng that he really thought people should crawl at his feet like his pet dog. His book praised Tongdaeng for crossing her paws in a canine wai when sitting on the floor, and said humans could learn how to prostrate by watching how his dog did it.

The tone of the book was ponderous and condescending, with facile homilies presented as profound wisdom — rather like the king’s long and meandering speeches to officials. As Malavika Reddy and Taylor Lowe wrote in an excellent and creative analysis of the Tongdaeng phenomenon:

Endearing perhaps to other dog lovers, the text repeatedly interprets unremarkable canine behaviors as signs of Tongdaeng’s distinctiveness. Tongdaeng’s enthusiasm for watching fish being fed is glossed as Tongdaeng’s “interest in fisheries.” The fact that, when commanded, Tongdaeng stops scratching becomes, in the text, an example of how quickly she learns. That Tongdaeng likes to lick the King’s hand evidences her loyalty and respect for His Majesty.

Also typical of Bhumibol was his insistence that he was more knowledgeable than everybody else. He wrote:

The King thoroughly studied the character, the behaviour and disposition of the Basenji. In fact, the King could be considered the foremost expert concerning the Basenji in Thailand. He understands the psychology of the dog, and how to deal with them.

His supposed expertise on the Basenji was demonstrated in the book with a couple of images taken from a German website that allegedly showed that the ancient Egyptian pharaohs kept Basenjis as pets. Commenting on an ancient carving showing a dog sitting under a pharaoh’s chair, Bhumibol declared:

It is strange that, when Tongdaeng was small, when she was with the King, she would crouch under his chair in that same manner.

He genuinely seemed to think he was sharing some extraordinary insight, rather than just noticing the obvious fact that a lot of dogs like to sit beneath their owner’s chair.

In most countries around the world, people would be outraged if a monarch expected them to crawl on the ground, and published a book telling them how to behave by comparing them unfavourably to his dog. But Thai royalists loved The Story of Tongdaeng. More than half a million copies were sold within a few months, making it the best selling book ever in Thailand.

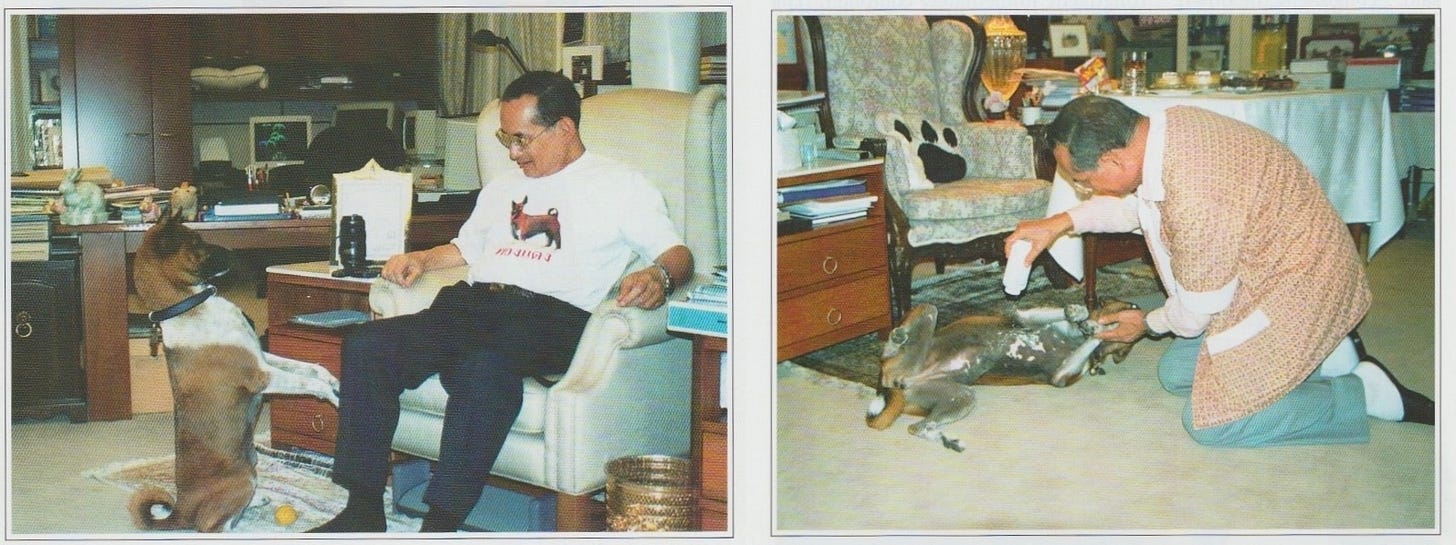

Photographs in the book gave an intriguing insight into Bhumibol’s life at Klai Kangwon. He had always enjoyed spending time alone, surrounded by gadgets like radios and walkie-talkies. Photographs of the interior of the palace in Hua Hin show rooms crammed with filing cabinets and desks groaning under numerous old PC monitors, printers, piles of documents and photograph albums. It’s unmistakably the home of an eccentric and somewhat obsessive old man. As Reddy and Lowe observe:

The collection of mundane objects, the piles of paper, and the clutter captured in the images are disarming.

Bhumibol was depicted with unprecedented informality in the photographs — wearing slippers and various dressing gowns and bath robes, or T-shirts with Tondaeng’s picture. In one image he was shown sprinkling talcum powder on her belly.

Living peacefully by the seaside with Tongdaeng and his many other pet dogs, Bhumibol at last seemed happy. That was why so many Thais loved the book.

The unspoken elegiac undertone of The Story of Tongdaeng was another reason the book was so popular. Thais knew that Bhumibol was getting closer to the end of his life, and were fearful about what would follow. The book had an intense — and bittersweet — emotional impact on the many Thais who revered the king.

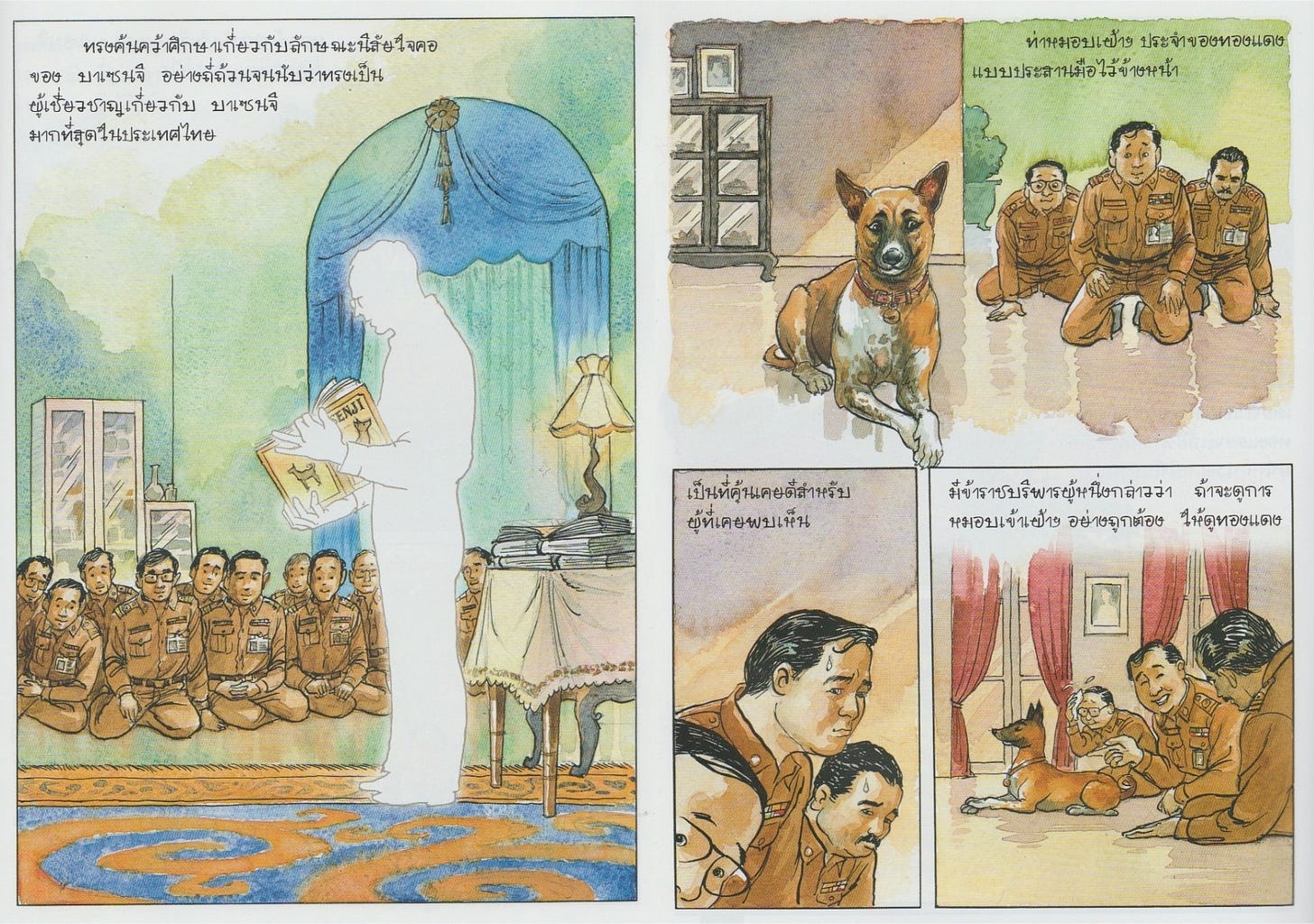

In 2004, a cartoon version was published, with illustrations by a team supervised by famous royalist political artist Somchai Katanyutanant, known as Chai Rachawat. The cartoons made the elegiac aspect of the book more explicit. Bhumibol was depicted as a spectral white outline, as if he was a ghost, or was slowly fading away. This was partly because it was considered disrespectful to draw a cartoon version of the king, but it also emphasised the painful fact that the era of Rama IX was drawing to a close.

The cartoons also emphasised the book’s reactionary subtext. Officials and soldiers were depicted sitting obediently at the feet of the king, and looking at Tongdaeng to learn how to prostrate correctly. Soldiers were even depicted in the same colour as Tongdaeng, to reinforce the message that Bhumibol wanted them to behave like obedient pets.

Bhumibol’s contented semi-retirement in Hua Hin was not destined to last. He was unable to end his habit of meddling in political events in Bangkok, and supported royalist plots to undermine Thaksin Shinawatra, who had become the most popular prime minister in Thai history. By 2006, Sirikit had turned against Thaksin too, and a palace-approved coup overthrew the prime minister and provoked an escalating political conflict. In October 2007, Bhumibol suffered a stroke and spent a month in hospital. In 2008, when the royalist Yellow Shirt movement was waging a violent campaign to bring down a newly elected government, Sirikit — who was far more extreme and interventionist than Bhumibol — relocated to Hua Hin so she could keep an eye on her estranged husband. His peaceful sojourn by the seaside was over.

Bhumibol became increasingly frail and depressed. After the Yellow Shirts caused a political crisis by storming Suvarnabhumi and Dong Muang airports in Bangkok in November 2008 and blockading flights, many Thais looked to him to make an intervention to defuse the situation, but there was silence. Sirindhorn explained that he was ill with bronchitis. In September 2009 Bhumibol was admitted to Siriraj Hospital in Bangkok with a fever and lung infection. Doctors cleared him to go home in early October, but Bhumibol refused to leave Siriraj. He remained at the hospital for the rest of his life, aside from a couple of brief spells at Klai Kangwon and Chitralada palaces. As US diplomats reported, Bhumibol’s decision to confine himself in hospital coincided with worsening infighting in the royal family, and several observers said the king was profoundly depressed:

There is clearly no way for anyone to analyze accurately the King's state of mind, or draw certain conclusions between political developments, possible mental stress, and his physical ailments. However, one long-time expat observer of the Thai scene, present in Thailand since 1955, has repeatedly asserted to us over the past year that the King shows classic signs of depression — “and why wouldn't he, seeing where his Kingdom has ended up after 62 years, as his life comes to an end” — and claims that such mental anguish likely does affect his physical condition/failing health.

Tongdaeng remained with Bhumibol at Siriraj Hospital. In March 2010, the king gave an audience to prime minister Abhisit Vejjajiva to show his support for the government as Red Shirt protesters began a campaign to demand new elections. But he still expected Abhisit to crawl on the floor beside Tongdaeng. It symbolised Bhumibol’s distaste for politicians, who he regarded as inferior to him, even the politicians he supported.

From 2006 onwards, Bhumibol’s annual New Year cards featured him posing with Tongdaeng and other favourite dogs. There was never any sign of other humans.

By 2011, Bhumibol had become desperately frail and decrepit. From time to time, he was brought out from Siriraj Hospital, with Tongdaeng at his side, to sit staring at the river. For centuries, the mythology of Thai royalty claimed kings had magical power to control the rain and the rivers, and Bhumibol’s short trips to the edge of the Chao Phraya were intended to reinforce this dying superstition.

The king was no longer well enough to interfere in Thai politics, and after Sirikit had a massive stroke while walking in the grounds of Siriraj in 2012, she was out of the game too. Vajiralongkorn consolidated his power, and as the inevitable royal succession grew closer, the military seized power in a coup in 2014 to manage the transition, and prosecutions for lèse majesté shot up as the regime tried to silence dissent.

Meanwhile, the regime was still trying to exploit Tongdaeng for royalist propaganda purposes, and in 2015 a risible animated film about the king’s favourite dog was produced, called Tongdaeng: The Inspirations.

In the feverish, paranoid atmosphere as Bhumibol’s reign drew to a close, even making jokes about Tongdaeng became a serious crime. Thanakorn Siripaiboon, a 27-year-old factory worker from Samut Prakan, was arrested at his home on December 8, 2015, charged with lèse majesté for mocking Tongdaeng in a Facebook post. He spent three months in jail before getting bail, and his legal nightmare didn’t end until he was finally cleared of all charges on January 13, 2021.

Towards midnight on December 26, 2015, Tongdaeng died at Klai Kangwon Palace in Hua Hin. She was 17 years and two months old. Bhumibol was comatose in Siriraj by this time, so ill that he probably never knew that his friend had died, and was not with her at the end. Public discussion of Bhumibol’s impending death was taboo in Thailand, so Thais talked on social media about Tongdaeng’s demise as a coded way of sharing their fears about the royal succession. As the BBC reported:

Tongdaeng's death will doubtless remind Thais of the increasing frailty of the 88-year-old king, and of the anxiety and uncertainty which still surrounds the succession to a new monarch.

Less than 10 months later, on October 16, 2016, Bhumibol died too.

For Rama IX’s cremation in October 2017, life-size sculptures of Tongdaeng and the king’s second favourite dog Tonglang were created by Chin Prasong, who had made statues of several of Bhumibol’s dogs while the king was still was alive.

The palace has tried to keep reverence for Bhumibol alive even after his death, to compensate for the obvious deficiencies of the new monarch, Vajiralongkorn. They have tried to keep the legend of Tongdaeng alive too.

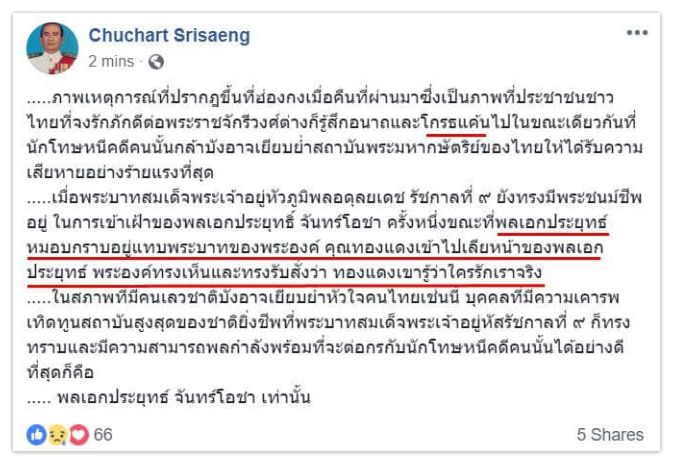

Ahead of the elections of March 2019, in which Prayut Chan-ocha and his allies sought democratic legitimacy for their regime that illegally seized power five years earlier, retired Supreme Court judge Chuchart Srisaeng urged Thais to vote for the junta party because Prayut had once been licked by Tongdaeng, which he regarded as proof that Rama IX supported him.

By this time, all of Tongdaeng’s children were dead too. But later in 2019, the Faculty of Veterinary Science at Kasetsart University announced they had successfully resurrected the royal canine lineage, using frozen sperm from two of Tongdaeng’s sons, Thong Ek and Thong Yip. So far, however, nobody has been able to resurrect respect for the monarchy, which has been destroyed by the antics of Vajiralongkorn.

To read the whole article, with discussion of Foo Foo, Luk Mee and Princess Perfume, please visit the Secret Siam website. Thanks for reading!