The palace and the pandemic

Thailand's royals are relentlessly trying to exploit the coronavirus crisis for propaganda, with disastrous consequences for the kingdom

I. Never let a good crisis go to waste

Thailand is on the brink of catastrophe as the Delta variant of the coronavirus rampages through the country. People are dying in the streets, with their bodies lying unclaimed for hours. Crematoriums are struggling to cope, and one literally collapsed under the strain of burning so many corpses. Hundreds of thousands of businesses that have barely managed to survive this long will fail in the weeks and months ahead as ever stricter lockdowns are imposed. More than 1.5 million people have fallen into poverty, raising the total above five million. There is no hope of the kingdom fully reopening in October, as prime minister Prayut Chan-ocha promised last month. Everyone fears what the next few months will bring.

But for the royal family, it’s a perfect opportunity for more shameless self-promotion and patronising propaganda.

An image posted on Facebook by Chulabhorn Hospital earlier this month (and later deleted) shows people waiting in a crowded room to be inoculated with the Chinese vaccine Sinopharm. Propped up in their laps are signs with the slogan “วัคซีนพระราชทาน” — “royally bestowed vaccine” — written in the special rajasap language used when mentioning matters related to the monarchy.

Their embarrassment and shame at having to be humiliated like this just to get vaccinated is clear from the photograph.

Princess Chulabhorn, the youngest sibling of King Vajiralongkorn, gave herself the power to import vaccines independently of the government on May 26. An edict published late in the evening in the Royal Gazette, and signed by the 64-year-old princess, decreed that she had awarded the Chulabhorn Royal Academy, her research and education institute, the authority to procure coronavirus vaccines, medicines and medical equipment.

It was a clear demonstration of where real power lies in Thailand. At the stroke of a pen, the palace can override government policy and do whatever it wants. Chulabhorn didn’t even bother to consult the cabinet in advance — public health minister Anutin Charnvirakul was blindsided and admitted he had been unaware of the plan until it was announced.

Anger was mounting at the government’s shambolic vaccine procurement strategy, as the kingdom fell ever further behind its neighbours in inoculating the population, and a wave of infections that began in high-end Bangkok hostess nightclubs spread through the kingdom. Chulabhorn’s intervention was widely interpreted as a rebuke of the government’s failings.

Chulalongkorn University professor Thitinan Pongsudhirak observed that “this vaccine bombshell could be perceived as a snub to the government of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, particularly Public Health Minister Anutin Charnvirakul”.

Fuadi Pitsuwan, son of late former foreign minister and ASEAN secretary general Surin Pitsuwan, wrote that the move “highlights the royal frustration and the split among the ruling elites over how the Prayut government is handling the crisis” and was a clear sign of palace displeasure:

The royal move, exercised in this manner however well-intentioned, calls into question the political legitimacy of the government and its authority in the management of the crisis. It is a no-confidence censure and a royal rebuke of both Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha and Minister of Health Anutin Charnvirakul.

The Academy began large-scale imports of Sinopharm from China, and Chulabhorn started heavily promoting her generosity providing the vaccine — even though Thais have to pay for it and the palace won’t lose any money at all from the scheme.

The price of the vaccine was set at strange amounts that suggest royal astrologers were consulted — initially Thais were charged 888 baht, and now some doses are being offered for 777 baht.

Large banners at Chulabhorn Hospital and other Sinopharm inoculation centres use the same “royally bestowed vaccine” slogan alongside images of the princess. The message is clear — this vaccine is a gift from Chulabhorn to the Thai people.

In a further humiliation for Anutin, he was summoned to kneel before Chulabhorn to ritually receive a fake box of Sinopharm. The symbolism could not have been more obvious — the palace was stepping in to do a job that the government had been failing to manage. Anutin had been unable to procure enough vaccine doses, so the royal family was intervening to save the day yet again.

According to Thai royal mythology, Chulabhorn is a brilliant scientist famous all over the world as a genius in the field of chemistry. In the late 1980s, her parents King Bhumibol and Queen Sirikit even tried to get King Carl Gustaf of Sweden to arrange a Nobel Prize for her, and according to Paul Handley in The King Never Smiles were “surprised and disappointed to be told that the Swedish king had no such power”.

In fact it’s not clear if Chulabhorn has any genuine scientific expertise at all, but she surrounds herself with some of the best and brightest in Thailand who do all the real work. Handley says that even for her graduate degree “her research work and papers were handled by a team of palace-supported scientists”.

Her high-profile intervention in Thai vaccine procurement was intended to show the superiority of royal wisdom and expertise over the incompetent efforts of government officials.

In any normal country, and any real constitutional monarchy, a princess intervening in vaccine policy in the middle of a pandemic without even coordinating with the government would be an extraordinary development. In Thailand, it’s just routine.

Thai royalists have never accepted the 1932 revolution that ended the absolute monarchy, and have never given up fighting to reverse it. A central part of this struggle involves relentless palace propaganda presenting the royal family as doing all the work to develop the kingdom and solve its problems, in contrast to avaricious and incompetent politicians who just cause more problems and never achieve anything.

This was why Bhumibol and the royals made so many theatrical visits to remote villages over several decades, with the king scribbling on maps with his pencil and telling officials what needed to be done. This kind of ad hoc, amateurish and disorganised approach was no substitute for a real systematic national development strategy, but it reinforced the belief that Bhumibol was single-handedly toiling to improve the lives of his people while successive governments did nothing.

As historian Tongchai Winichakul wrote in his article Toppling Democracy, the king’s so-called royal projects were a crucial part of his mythmaking:

The truth about these projects, and their successes and failures, will probably remain unknown for years to come, given that public accountability and transparency for royal activities is unthinkable. Suffice it to say that the endlessly repeated images of the monarch travelling through remote areas, walking tirelessly along dirt roads, muddy paths and puddles, with maps, pens and a notebook in hand, a camera and sometimes a pair of binoculars around his neck, are common in the media, in public buildings and private homes. These images have captured the popular imagination during the past several decades. Bhumibol is portrayed as a popular king, a down-to-earth monarch who works tirelessly for his people and, we may say, has been in touch with his constituents for decades long before any politicians in the current generation began their career.

Bhumibol was portrayed as an expert in everything who had to chide politicians to get them to follow his brilliant insights. In the 1990s he started appearing on television lecturing officials on how to solve Bangkok’s perennial traffic problems. He had no expertise in the subject at all, but it reinforced the notion that only the king had the will and the wisdom to solve the issue. As Handley says in The King Never Smiles:

The average TV viewer got no information on the utility of his ideas, and even fewer understood that there was already a whole bureaucracy working on traffic problems, backed by international expertise. It appeared like only the king was confronting the problem.

Whenever Thailand faced a crisis or disaster — floods, droughts, cyclones — royal relief efforts were given endless publicity. It was never clear where the money came from — some of it was raised from donations but much of it was actually state funds, paid for with the taxes of the people. But it was presented as more evidence of royal benevolence, a gift from the king.

The exaltation of Bhumibol and the modern Thai monarchy as the source of everything positive in Thailand was part of a broader narrative taught to generations of children which depicted the whole of Thai historical progress as the achievement of a succession of brilliant monarchs. In his study Thailand’s Hyper-Royalism: Its Past Success and Present Predicament, Thongchai observes:

Thai history is a collective hagiography of great kings who were leaders and exemplars in military, statecraft, diplomacy, trade, arts and literature. Many of them are celebrated as the “Fathers” of almost every aspect of the life of the nation. This history reinforces the belief that the making of the Thai nation is impossible without the monarchy.

The implication of all of this is that it was a terrible mistake to end the absolute monarchy in 1932 because this meant the palace now has to contend with useless and corrupt politicians to get anything done. It’s a compelling narrative for many Thais because of course a large number of politicians are indeed useless and corrupt, not least the current government. But it’s a toxic distortion of history that infantilises the Thai people and denies their role in improving their own lives.

Instead of being treated as citizens who deserve a competent government, Thais are taught they are subjects of a benevolent paternalistic monarchy and must be grateful to the palace for everything they receive. National development, disaster relief and even democracy itself are not something Thais have a right to expect — they are gifts from the royal family. The whole history of 1932 has been rewritten to claim King Prajadhipok himself graciously bestowed democracy upon the nation.

The attitude expected from Thais was satirised with the image of Khun Sapsueng, the symbol adopted by the legendary Same Sky web board where online debate about the monarchy began flourishing 15 years ago — an emoji weeping with gratitude for everything the monarchy had done.

Over the decades, the palace learned never to let a good crisis go to waste. It could always be exploited to boost the image of the monarchy and undermine the constitutional system of government. So it was inevitable that the royals would seek to take advantage of the coronavirus pandemic to bolster their exalted position.

But the problem for the monarchy is that Vajiralongkorn and his siblings and children are incapable of playing the same role as Bhumibol in promoting the mythology of a wise and paternalistic palace. Their efforts to exploit the pandemic for propaganda purposes began as comically inept, and later caused a disastrous policy decision that led directly to the kingdom’s current dire predicament.

II. Royal Benevolence Has Brought Great Joy and Appreciation to the People

On March 1, 2020, Thailand announced its first death from the coronavirus, a 35-year-old man who worked in a King Power duty free shop. It was becoming clear that the pandemic was a global emergency and extreme measures had to be taken to contain it.

Defenders of the continued existence of royalty in the 21st century say a monarch can play a crucial role at a time of national crisis by uniting and reassuring the country. But Vajiralongkorn was nowhere to be seen. He wasn’t even in Thailand.

As his kingdom struggled with the gathering storm, Vajiralongkorn was five-and-a-half thousand miles away at the luxurious Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl in Bavaria, frolicking with a large harem of women, going on bicycle rides through the Alpine countryside, and doing his best to ignore the outside world.

Vajiralongkorn had been living in Germany since 2007, with brief trips to Thailand for essential rituals and ceremonies. This fact had never been officially revealed to Thais, but by 2020 it was common knowledge, partly thanks to work by Somsak Jeamteerasakul, Pavin Chachavalpongpun and me, amplified on social media which the regime was unable to censor. European media, and particularly the aggressive German tabloid BILD, were also starting to take an interest in the king’s antics. So his presence in Bavaria could no longer be kept hidden.

Vajiralongkorn had been widely despised in Thailand since the 1970s, but by 2020 he was hated more than ever, particularly after the Constitutional Court dissolved the progressive Future Forward Party on the orders of the palace on February 19. There was unprecedented criticism of the king on Twitter and Facebook, and “flash mob” protests were held at universities and schools all over the country, with signs and banners openly mocking the monarch, something that had been previously unthinkable in Thailand.

There was anger and incredulity when it emerged that Vajiralongkorn had no intention of interrupting his 13-year taxpayer-funded holiday in Germany just because of a deadly pandemic. Bavaria announced a lockdown on March 20, with hotels and restaurants closed, and residents only allowed to leave their homes for essential reasons. But instead of leaving Germany and heading back to Thailand, Vajiralongkorn’s servants applied for a special permit from the Bavarian authorities to remain at Sonnenbichl. It was granted, with the justification that the king and his entourage were “a single, homogenous group of people with no changes”.

In fact, however, Vajiralongkorn’s large entourage in Germany posed a significant risk of transmitting the disease. The king and his staff routinely ignored the strict lockdown rules, and several palace servants in Germany had already caught the virus.

In an effort to contain the outbreak, 119 staff were sent back to Bangkok on a Thai Airways flight on March 22. After arriving in Thailand on March 23 they were quarantined at various army hospitals in the capital. Nobody informed the German authorities that several members of the entourage who flew back to Thailand via Munich Airport showed symptoms of covid-19. Vajiralongkorn remained in Bavaria with a much smaller group of staff and servants.

Meanwhile, an unprecedented amount of information was being leaked by senior Thai sources who were appalled by Vajiralongkorn’s behaviour. At the end of March I published a detailed article on the king’s lifestyle in Germany, based on information from several insiders who confirmed that the king had a harem of around 20 women at the Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl. They had all been given a royally bestowed surname, Sirivajirabhakdi, and they were organised in a military-style unit which Vajiralongkorn called the SAS, in homage to Britain’s Special Air Service elite force.

Sources said Vajiralongkorn and the harem occupied the entire fourth floor of the hotel, including a special suite he called “the pleasure room”. Queen Suthida had been packed off to Switzerland where she was living a separate life at the Hotel Waldegg in Engelberg.

Vajiralongkorn and Suthida had been due to return to Thailand for a week in April, to mark Chakri Day and then the beginning of the Songkran holiday. But the government was forced to cancel Songkran events because of the pandemic, and in the end the king and queen visited for less than 24 hours, arriving early in the morning of April 6 and leaving during the night. In another sign of the resistance to Vajiralongkorn even within the palace, the schedule for the trip was leaked to me in advance.

By April 7, Vajiralongkorn and Suthida were back in Europe. The brief visit had required bankrupt national flag carrier Thai Airways to organise two return flights by a Boeing 777 from Bangkok to Zurich purely for the royal entourage.

Although the king and queen had spent less than a day in the kingdom, the palace desperately tried to pretend that the royal family was working hard and making generous donations to help those affected by the pandemic.

Bags of supplies, printed with large white letters declaring they were charity from the palace, were distributed to Bangkok slum residents by members of the royalist “Volunteer Spirit” organisation. Recipients were told to place a table or chair outside their front door, because the bags — which contained a small amount of rice, instant noodles, and soap — were holy royal artefacts which should not be allowed to touch the ground. Residents were also ordered to pose for photographs with portraits of the king.

In fact, the budget for the modest relief packages came from taxpayer funds, and the royal branding was purely for propaganda. Leaked footage showed Channel 3 royal correspondent Malinee Wanthong badgering an elderly couple to hold up a picture of the king and express their gratitude to the monarchy.

At the end of April, the palace released a video intended to highlight the generosity of the monarchy, entitled “Royal Benevolence Has Brought Great Joy and Appreciation to the People.” They even added English-language subtitles.

Recipients of royal relief supplies were filmed expressing their great joy and gratitude, but they looked scared and downtrodden rather than joyful and grateful. The video achieved North Korean levels of clumsy and ridiculous denial of reality.

The captions declared:

Their Majesties the King and Queen have graciously distributed relief supply bags in the capital to members of the public who are facing difficulties in life caused by the COVID-19 outbreak.

But of course, Vajiralongkorn and Suthida hadn’t personally distributed any supplies at all. They were far away at luxury hotels in Europe. One man, visibly trembling, said: “Their Majesties never forget their people.” But everybody knew that Vajiralongkorn had no interest in the welfare of the people, and he couldn’t even be bothered to spend time in Thailand as the country grappled with the pandemic.

Daily royal news broadcasts began regularly publicising donations of medical equipment and supplies supposedly made by the monarchy — ventilators, portable X-ray devices, mobile biosafety units, face masks, protective gear. But as usual it wasn’t clear where the money had come from, or whether these donations had been coordinated with the government to ensure they were what was most needed, or were just handed out on an ad hoc basis. As with Bhumibol’s development trips in the Thai countryside, there was no sign of any coherent plan at all.

Meanwhile, the king’s youngest daughter Princess Sirivannavari was also trying to exploit the pandemic to boost her image and advertise her eponymous fashion brand. Copying the French luxury goods conglomerate LVMH, which had converted three of its perfume factories to produce hand sanitiser as the virus swept through Europe, the princess announced that her Sirivannavari couture company would also begin making the product.

But unlike LVMH, the Sirivannavari corporation had no perfume factories to convert. Instead, pharmacists at Chulalongkorn Hospital were ordered to produce the hand sanitiser, and the princess just provided the Sirivannavari branding and claimed the credit. The whole project was purely a marketing stunt.

To add insult to injury, Sirivannavari marked the launch of the sanitiser by releasing photographs on social media showing her dressed as a doctor with her favourite pet dog, the Yorkshire terrier Princess Perfume, wearing a nurse’s hat.

All over the world, the behaviour of the royals was generating embarrassing media coverage. German international broadcaster DeutscheWelle summed up the situation: “Thailand's king living in luxury quarantine while his country suffers.”

May 1 was the first wedding anniversary of Vajiralongkorn and his fourth wife Suthida, and to mark the occasion the palace released official photographs that showed the couple inspecting relief efforts at an army base, dressed in matching tracksuits.

Suthida was photographed sewing a face mask as her husband watched. The images were intended to give the impression that the king and queen were in Thailand and toiling to support efforts to combat the coronavirus.

In fact, they had spent less than 48 hours in the kingdom since the beginning of 2020, and the photographs had been hastily staged during their April 6 visit — as could be seen from the date in the URLs of the images, which the palace forgot to remove.

Vajiralongkorn had been due to come back to Bangkok for the first anniversary of his coronation from May 4 to 6, and stay for Visakha Bucha Day on May 7 and the Royal Ploughing Ceremony on May 11. But with Thailand still in lockdown, the visit was cancelled.

On May 20, in an absurd ceremony attended by Prayut, army chief Apirat Kongsompong, police chief Chakthip Chaijinda and the government team handing the pandemic, the single face mask sewn by Suthida in April was handed over, and handled with great reverence as if it was some kind of sacred artefact.

Four days later, Vajiralongkorn set off on a cycling trip in Bavaria accompanied by an entourage of around 20 people including at least one of his harem, and one of his pet white poodles. The strange scene was filmed by a bystander and the footage was given to BILD. The video showed the reality of the king’s life in Germany — far from working tirelessly to help Thailand overcome the pandemic, he was pedalling around the Bavarian countryside semi-naked with one of his concubines.

Thailand managed to keep the coronavirus under control for most of 2020, and the country was praised around the world for its success. But it was clear that royal efforts to use the pandemic to promote their prestige had been calamitously counterproductive. They only succeeded in highlighting that Vajiralongkorn was far away, didn’t care, and was spending vast amounts of taxpayer money at a time when many Thais faced destitution due to the absence of foreign tourists.

The jarring contrast between his luxurious lifestyle abroad and the plight of ordinary people fuelled mounting anger towards the royals. After the kidnap and murder of Wanchalearm Satsaksit in Cambodia reignited the protest movement, democracy activists began openly demanding reform of the monarchy, another unprecedented development in Thailand.

At huge mass rallies in August and September, Vajiralongkorn’s absence from his kingdom was mocked and criticised. One leading activist, Chukiat Saengwong, began attending protests dressed in a crop top with a headband in the colours of the German flag, to highlight the king’s ongoing holiday in Bavaria and his strange fetish for frequently appearing in public in Germany dressed in eccentric clothing.

In September, pro-democracy billionaire Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit openly questioned why Thailand was funnelling so much money to the monarchy when the economy was in crisis:

People are getting furious about this, especially when you look at the macroeconomy. Thailand’s GDP growth is projected to be negative 8 per cent at best this year, so we need all the resources we have to spend on the recovery.

Faith in Thailand’s monarchy had collapsed, and the king’s behaviour during the pandemic was one of the main reasons.

But behind the scenes, a plan was being hatched that the palace and government hoped would repair the damage and restore reverence of the royals.

III. A royal vaccine

The holy grail for the regime was a vaccine made in Thailand that could be presented to the people as coming from the king. They believed that if this could be achieved, it would be a huge boost for the monarchy, the latest glorious chapter in the mythical royal history of visionary kings saving the country at time of crisis.

There was no prospect of Thai scientists being able to develop a vaccine fast enough to compete with international giants like Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca. But the next best thing was for Thailand to manufacture vaccine doses under license from one of the global industry leaders, and to find a way to give the project royal branding.

Drug companies were racing in 2020 to develop viable vaccines while also trying to plan ahead for production of immense quantities so that as much of the world’s population as possible could be inoculated. During the early months of 2020, AstraZeneca was already looking for production hubs around the globe that could start mass-producing doses quickly once a successful vaccine had been approved.

Thailand was an obvious choice for a southeast Asian hub, particularly because of its strong domestic scientific expertise and excellent transportation and distribution links. Talks between the Thai government and AstraZeneca began in March 2020.

The most logical partner for AstraZeneca in Thailand was the Government Pharmaceutical Organization which had been working for more than a decade to develop the expertise and infrastructure to produce vaccines in the event of a pandemic.

After Thailand struggled to buy vaccines during the H1N1 swine flu pandemic in 2009 which killed around 300,000 people around the world, the government decided to develop domestic production capacity via the GPO with the construction of a factory in Saraburi able to make doses for both seasonal and pandemic influenza on an industrial scale. An agreement was signed with the World Health Organisation, and US pharmaceutical company Schering-Plough offered technology transfer.

The opening of the influenza vaccine plant in Saraburi was dogged by repeated delays, and the egg-based methods it used were different from the technology required to produce the AstraZeneca vaccine. But the basic infrastructure was in place and the Saraburi plant could have been repurposed. It would not have been easy or straightforward, but with the help of AstraZeneca, which was offering technology transfer, it was the most sensible solution if Thailand wanted to start mass-producing coronavirus vaccines as quickly as possible.

Palace officials, however, pressured the government to use an obscure royal company instead — Siam Bioscience, founded in 2009 during the reign of King Bhumibol as part of the sprawling portfolio of businesses in the Crown Property Bureau, the opaque royal conglomerate that quietly dominates the Thai economy.

The main assets of the CPB are large stakes in Siam Cement Group and Siam Commercial Bank, plus vast land holdings, but there is also an extensive web of shareholdings and smaller companies. During Bhumibol’s reign, the palace maintained the fiction that the Crown Property Bureau belonged to the Thai nation, but this was never true, and in 2018 Vajiralongkorn officially took ownership of all CPB assets, worth at least $80 billion and probably much more.

Siam Bioscience had no experience at all of vaccine production. It made two products, at a relatively small scale — erythropoietin, used to treat patients with chronic renal failure, and filgrastim, for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Most Thais had never heard of the company before 2020.

But Siam Bioscience had many advantages in terms of royal propaganda potential. It was owned by the king himself. It was founded during Bhumibol’s reign and claimed to operate according to his ideology of ‘sufficiency economy”, producing medicines in Thailand so the country could be more self-reliant. Most of the employees were proudly royalist — a corporate news item from September 2019 shows company staff on an environmental outing to the beach, with all of them wearing “Volunteer Spirit” uniforms.

Palace officials had realised early in 2020 that Siam Bioscience could be leveraged to create positive publicity during the pandemic. The company worked with the Department of Medical Science to produce RT-PCR coronavirus test kits and delivered the first batch of 20,000 to Government House on April 16.

In a clear sign there were big plans afoot to use the company for propaganda, royalist socialite Nualphan Lamsam installed herself as “honorary director of corporate communications” and began making statements to the media on behalf of Siam Bioscience. Known as “Madam Pang” and described as “famously attractive” by the Bangkok Post, she is a member of the immensely wealthy Lamsam family which founded Thai Farmers Bank in 1945, and has a flair for self-promotion, with more than 1.4 million followers on Facebook and half a million on Instagram. She was manager of Thailand’s national women’s football team for years and remains a major benefactor. She also owns the Thai club Port FC and is routinely given more prominence in team publicity than the players.

Nualphan is close friends with Sirivannavari and is regularly photographed kneeling at the feet of the princess — even when abroad which tends to raise eyebrows in countries not accustomed to prostration. Her husband Naras Savestanan is close to Vajiralongkorn and was made a deputy lord chamberlain at the Royal Household Bureau after his retirement as director-general of the corrections department in September 2020.

The government was easily convinced to make Siam Bioscience the cornerstone of its vaccine strategy. Prayut is a fervent royalist who is terrified of Vajiralongkorn and is constantly trying to placate and please him. He believes the monarchy must be preserved at all costs. Anutin has spent years trying to cultivate close ties with Vajiralongkorn — a leaked US cable from 2009 discussing Vajiralongkorn’s inner circle noted that: “A relatively new close associate and princely financier is banned former Thai Rak Thai politician Anutin Charnvirakul”. Anutin frequently visited Vajiralongkorn in Germany over the past decade, accompanying him on shopping trips around Europe.

Both Prayut and Anutin quickly agreed with palace officials that they should sideline the GPO and try to get AstraZeneca to partner with Siam Bioscience, and for much of 2020 this was the main focus of the government’s vaccine strategy.

They didn’t bother to do serious analysis of how many doses Thailand required and how soon they were needed, because they had become complacent due to the kingdom’s apparent success in containing the virus during 2020. There was a bizarre lack of urgency about actually securing enough doses to vaccinate enough Thais to achieve herd immunity. They were fixated with ensuring that Siam Bioscience would be chosen by AstraZeneca as its southeast Asian partner.

Prayut has claimed that “there were other manufacturers which had offered to produce the jabs, but Siam Bioscience was selected because it met all of the government's criteria” but the regime has never revealed these criteria. Indeed, there are no credible criteria under which Siam Bioscience would have been a better choice than the Government Pharmaceutical Organization. The decision was purely based on a desire to promote the monarchy.

AstraZeneca did due diligence on Siam Bioscience in the second quarter of 2020, focusing on anti-bribery and anti-corruption measures, supply chain security, human rights safeguards and financial health. But they were moving at haste to identify potential partners and appear to have failed to consider the potential political risks of going into business with a company belonging to Thailand’s king.

By the second half of 2020, talks were at an advanced stage. On September 7, Anutin and a team from the Ministry of Public Health met AstraZeneca representatives in Bangkok to discuss the agreement. We know from a leaked letter to Anutin from Sjoerd Hubben, AstraZeneca’s vice president for global corporate affairs, that during this meeting the Thais were extremely relaxed about the number of doses needed, saying: “Thailand’s healthcare system required approximately three million doses per month”.

We also know from the letter that AstraZeneca advised Thailand to sign up for the COVAX scheme, an international initiative involving the World Health Organisation, GAVI and UNICEF designed to help low and middle-income countries gain equitable access to coronavirus vaccines.

A month later, on October 12, a letter of intent was formally signed at the Ministry of Public Health with the Thai government, AstraZeneca, Siam Bioscience and Siam Cement Group agreeing to work together to create a large-scale vaccine production plant to supply doses to southeast Asia.

SCG was brought into the deal because Siam Bioscience didn’t just lack the technology to make the vaccine, it also didn’t have a big enough production facility, so a new one would have to be built. The government subsidised the new plant construction with 600 million baht while SCG contributed 100 million.

Anutin signed the deal on behalf of the Thai government, and Vajiralongkorn’s right-hand man Satitpong Sukvimol signed for Siam Bioscience. Satitpong is an air chief marshal who has been private secretary to Vajiralongkorn since 2005 and has become the most powerful person in the king’s inner circle. He was made grand chamberlain of the Royal Household Bureau in 2017 and chairman of the Crown Property Bureau in 2018, putting him in overall charge of Vajiralongkorn’s finances and the vast palace bureaucracy. His younger brother Torsak is head of the special police division of the King’s Guard. The brothers have been implicated in systematic interference in police promotions.

Satitpong could have signed on behalf of Siam Cement Group too — he’s also chairman of the conglomerate, as well as several other royal companies including Deves Insurance, Siam Sindhorn and Doi Kham — but instead SCG chief executive Roongrote Rangsiyopash represented the firm. James Teague, AstraZeneca’s country president in Thailand, was in the UK and signed the agreement at the Thai embassy in London.

Anutin, Satitpong and Roongrote all wore yellow ties — the king’s colour.

IV. The work of the institution we revere and love

Thai officials were jubilant that they had managed to secure the partnership with AstraZeneca. After the deal had been signed, they didn’t appear to think actually procuring enough vaccines to inoculate most of the population was a particularly high priority.

An agreement to buy vaccines from AstraZeneca was not concluded until November 27, and Thailand only ordered 26 million doses, enough to inoculate just 13 million people, around 20 percent of the population. This absurd decision was based on a combination of complacency, ignorance and a determination to spend as little money as possible.

The government initially budgeted only six billion baht for vaccine procurement in 2021, a ridiculously paltry amount in a country with a 2021 defence budget of 223.4 billion baht. They planned to procure a further 66 million doses in 2022, when they believed the price would be substantially lower, and to have 70 percent of Thais vaccinated by the end of that year. The pandemic is an infinitely greater danger to Thai national security than any conceivable military threat from an external enemy, and it’s unforgivable that the regime was trying to fight the virus on the cheap.

They thought the coronavirus was under control and there was no hurry to vaccinate the majority of the population, not understanding that the only way the kingdom could safely reopen to tourists and revive its collapsing economy was by inoculating enough Thais to achieve herd immunity as quickly as possible. Until that target was reached, the continued closure of Thailand’s borders would result in vast economic losses and drive hundreds of thousands of small businesses into bankruptcy.

The obsession with relying on a royal vaccine led to multiple disastrous missteps. Thailand declined to join COVAX, one of only seven countries in the world to opt out alongside international pariahs like North Korea and Belarus. The regime agreed to accept two million doses of Sinovac, not wanting to offend the Chinese, but an offer of vaccines from India was rejected.

The story they wanted to tell was that Thailand had achieved self reliance thanks to the wisdom and foresight of Bhumibol and the generosity and determination of Vajiralongkorn, and was defeating the coronavirus with a vaccine bestowed by the king. Accepting international help didn’t fit with this triumphant nationalistic narrative and would require the monarchy to share the credit with foreigners, which they were not willing to do. Thailand would go it alone.

Basing the country’s entire inoculation strategy on a single vaccine, aside from a small symbolic amount of Sinovac doses, was exceptionally risky. Most countries aimed for vaccine diversity, in case some brands proved unsafe or less effective, but Thailand was gambling everything on AstraZeneca.

Moreover, because extensive work had to be done to build a big enough production facility for Siam Bioscience, on top of the time taken for technology transfer, domestic production of the AstraZeneca vaccine would only begin in the middle of 2021, which was months away. Until then, the vast majority of Thailand’s people would be left defenceless against the virus.

Choosing to focus on promoting the image of the monarchy rather than just vaccinating as many people as possible quickly and efficiently was a disastrous decision that led directly to Thailand’s current dire predicament.

“By securing 26 million doses, we are assured that our people have access to an effective and safe vaccine,” proclaimed Prayut at the November 27 signing ceremony for the AstraZeneca order. “In addition, this is an important opportunity to demonstrate the strength of Thailand’s biopharmaceutical manufacturing industry and the critical role it plays in South East Asia and beyond.”

Within less than a month, everything began to unravel.

On December 17, a 67-year-old woman who sold prawns at the vast Mahachai seafood market in Samut Sakhon tested positive for covid-19. There were four cases the following day, and soon the number had climbed into the hundreds. Always eager to find a foreign scapegoat to blame, the government said illegal Myanmar migrants had brought the virus into the market. The workers were ordered to remain in their cramped dormitories and the area was encircled by barbed wire to prevent them from leaving.

But the outbreak spread beyond Samut Sakhon, reaching most of Thailand’s provinces, in the most serious coronavirus crisis the country had faced since the start of the pandemic. Underground gambling dens in the capital, most of which are run by the police and military, were another major vector of transmission, and deputy prime minister Prawit Wongsuwan was ridiculed after he claimed: “I don't believe illegal casinos are operating in Bangkok”.

The second wave peaked on January 29, 2021, when there were 1,732 new cases. It was a warning sign that Thailand’s success in containing the virus in 2020 was more due to luck than sound policies.

As the country plunged into the second wave of the virus, the government belatedly realised that its order of 26 million vaccine doses was woefully inadequate. On January 5, Prayut announced that Thailand had ordered an additional 35 million AstraZeneca doses, bringing its total expected supply in 2021 to 63 million doses — 61 million AstraZeneca and two million Sinovac — which would be enough to inoculate about 45 percent of the population.

But this was fake news. It was true that the government approached AstraZeneca in January 2021 to request an additional 35 million doses, but by this stage the company had already signed deals with Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, Brunei and the Maldives. Siam Bioscience did not have the capacity to produce another 35 million doses by the end of 2021 on top of what had already been agreed. The Thais had missed their chance to order a sensible number of doses.

AstraZeneca tried to find a compromise, because they didn’t want to alienate the government of the country where their southeast Asian production hub was located, and after months of negotiations the order was finally agreed in May, but with no timeframe specified. Thailand would get another 35 million doses but there was no guarantee they would arrive by the end of 2021.

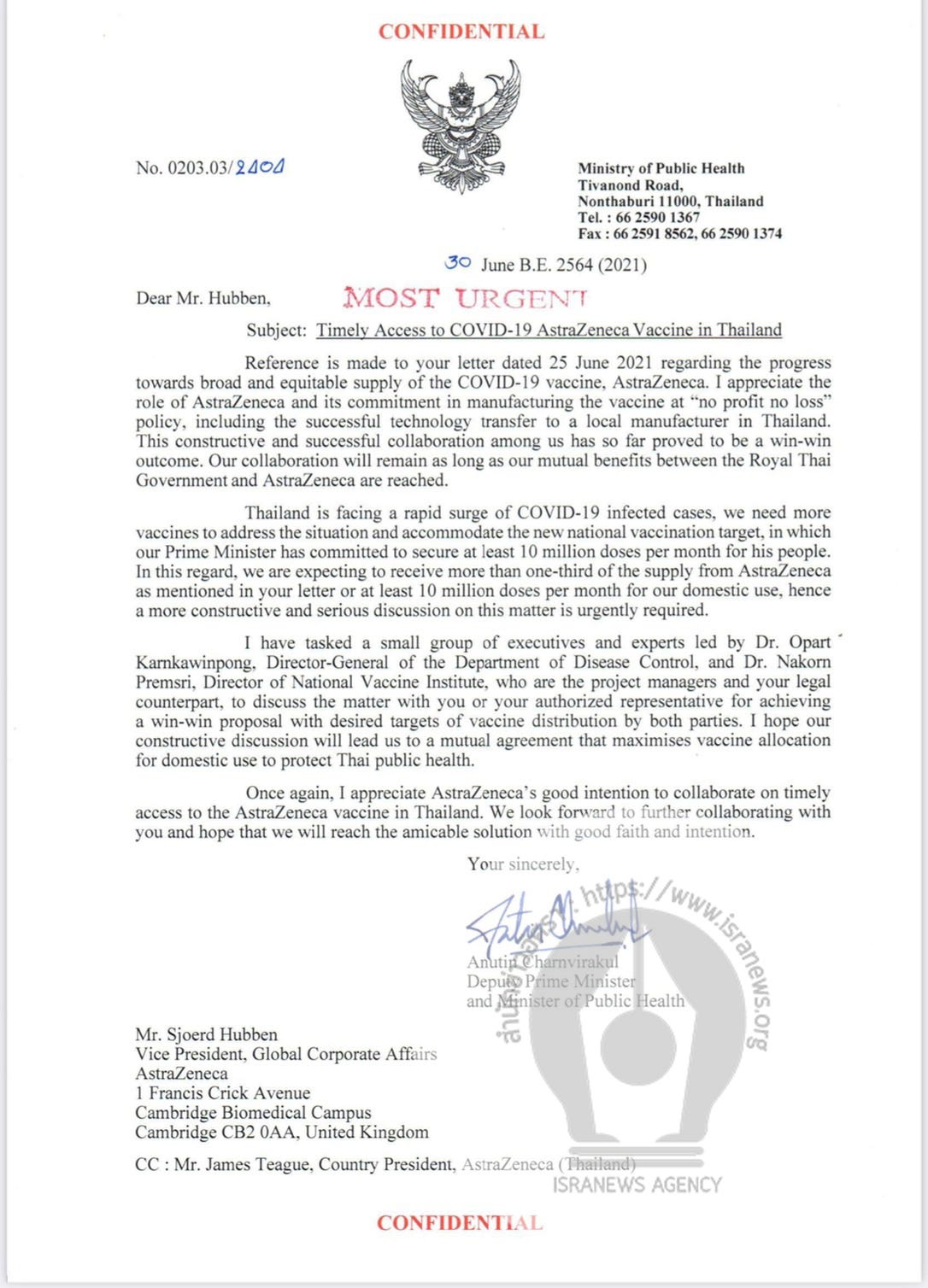

So Prayut and Anutin were lying to the Thai people for months — between early January 2021 when they started claiming they had secured an order for another 35 million doses, and May when AstraZeneca finally agreed. The leaked letter from AstraZeneca sets out all the countries that had ordered vaccine from Siam Bioscience, and the month the deal was agreed. Thailand was way behind other nations.

Thai officials also began claiming, falsely, that all the doses would be delivered during 2021. AstraZeneca had not made this commitment and it was not included in order contracts with Thailand. There was considerable uncertainty about what Siam Bioscience production capacity would be, because it is very hard to predict output at new plants, as AstraZeneca CEO Pascal Soriot explained in an interview in January:

A year ago, we didn't have a vaccine. When you do that, you have glitches, you have scale-up problems. Therefore, the yield varies from one to three, by the factor of three.

In other words, production at new facilities can vary wildly. Especially at first, some facilities can produce three times more doses than others relative to capacity. Forecasts cannot be made with any certainty.

As the second wave of the virus punctured the myth that Thailand was a covid-19 success story, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit broadcasted a devastating critique of the regime’s policy failings. In a half-hour talk on Facebook Live on January 18 he noted that other countries were already beginning to inoculate their citizens, while mass vaccinations in Thailand would not start for several months, and pointed out that relying so heavily on AstraZeneca was exceptionally risky, especially because Siam Bioscience had never produced vaccines before.

The regime was thrown into a state of panic. The plan for a royal vaccine was being questioned and they knew that delivery of AstraZeneca doses was months away. Meanwhile, other countries in the region were far ahead, thanks to doses received via the COVAX scheme or donated by India. Thailand was being left behind, and there was no credible justification for this.

On January 19, officials held a news conference to try to defend their strategy, but they were unable to provide coherent reasons for relying so heavily on AstraZeneca and failing to seek other vaccines. Supakit Sirilak, deputy permanent secretary at the Ministry of Public Health, claimed:

We are currently negotiating with many vaccine companies, but due to the need for confidentiality we have not made the details public. The procurement process may be a bit slow as we have to study the vaccine first. I would like to confirm that it is not too slow.

All of this was untrue. Thailand was not negotiating with many vaccine companies, there was no need for confidentiality, and the failure to seek alternative vaccines had nothing to do with having to “study” them, it was because the regime wanted to focus on a royal vaccine. With Thailand in the grip of a second wave, the procurement process was far too slow.

National Vaccine Institute director Nakhon Premsri tried to use royalist myths to defend the policy, saying the country was creating a vaccine “in accordance with the philosophy of King Rama IX, under which Thailand has laid the health foundation and built medical expertise over 10 years”. He claimed Thanathorn’s criticisms were an attack on the monarchy: “These baseless and inaccurate accusations shouldn’t be linked to the work of the institution we revere and love.”

Prayut threatened legal action against anybody questioning the government’s vaccine procurement plans: “It’s all distorted and not factual at all. I will order prosecution for anything false that gets published, whether in media or social media.”

Sure enough, the following day the government took the extraordinary step of lodging lèse majesté and computer crimes complaints against Thanathorn, just because he had questioned their overreliance on AstraZeneca. Thanathorn was defiant, telling a news conference:

Prayut has always used the royal institution to hide the inefficiency of his administration, saying that he is loyal to the monarchy and protecting it. Is this not why many people are raising issues with the monarchy institution? The person bringing up the monarchy in the vaccines issue is not me, but Prayut.

He again highlighted that Thailand’s strategy meant the country would be far slower than others in getting the population vaccinated:

Since Thailand is acquiring and distributing vaccines at a slower rate than other countries, what do you think will happen to our economy? Having vaccines is like having a light at the end of the tunnel, and finally being released from the terrible economy caused by covid. But as of today, we are still in the tunnel. As long as not enough Thais have gotten vaccinated, we are still in the dark.

Anutin responded on Facebook with an open letter to Thanathorn in which he claimed: “Let me confirm that the purchase of 61 million AstraZeneca doses and 2 million Sinovac doses are the best choice for Thais and Thailand.”

Meanwhile, Madam Pang issued a statement on behalf of Siam Bioscience defending the company’s expertise and declaring:

For the well-being of people and the economy, both in Thailand and the region, having decided to drastically alter its manufacturing plan in order to pour all available resources and efforts into manufacturing the vaccine as specified by AstraZeneca as expeditiously as possible, Siam Bioscience staff are working tirelessly, competing against time. Thus Siam Bioscience is determined to help ensure a better tomorrow for Thai people and all of mankind.

By now, democracy activists were starting to criticise the royal vaccine strategy too. On January 19, Benja Apan, a 21-year-old Thammasat University student, staged a lone protest outside the $1.7 billion luxury IconSiam mall — owned by the royals via the Siam Piwat holding company — with a sign that read: “Vaccine Monopoly is PR for the Royals”. She was assaulted by a security guard. On January 23 there was a light projection protest at the Siam Bioscience headquarters, with critical slogans beamed onto the building, and on January 25 protest leaders including Parit “Penguin” Chiwarak gathered outside to demand transparency.

The regime was still desperately trying to salvage the propaganda potential of the royal vaccine by stifling criticism. The digital economy ministry obtained a court order demanding that Thanathorn take down his video, claiming the remarks threatened national security. Thanathorn refused.

Officials also tried to justify why Thailand was the only country in ASEAN, and one of just a few countries in the world, to decline to join the COVAX scheme, but as usual the excuses were dishonest and nonsensical. “Buying vaccines directly from the manufacturers is an appropriate choice... as it’s more flexible,” claimed government spokesman Anucha Buraphachaisri. “If Thailand wants to join the COVAX program, it will have to pay for vaccines itself with a high budget and there is also a risk.”

On March 30, Thanathorn was formally charged with lèse majesté for questioning the regime’s vaccine policy.

V. My heart aches

By now, the second wave of the virus had been contained. But in April, Thailand was plunged into a devastating third wave that cruelly exposed the inadequacy of the regime’s plans.

An outbreak of the Alpha variant that began in Thonglor hostess bars infected several government officials including transport minister Saksayam Chidchob, and some senior police officers who should have closed down these illegal venues but instead enjoyed drinking and partying there too. By failing to implement strict measures ahead of the Songkran holiday when hundreds of thousands of people left Bangkok to return to their hometowns, Prayut enabled the spread of the virus to every corner of the kingdom. As Associated Press reported:

The latest crisis has made glaringly apparent an Achilles heel in Thailand’s strategy, a failure to secure enough doses this year to inoculate a targeted 70 percent of the population believed necessary to achieve herd immunity.

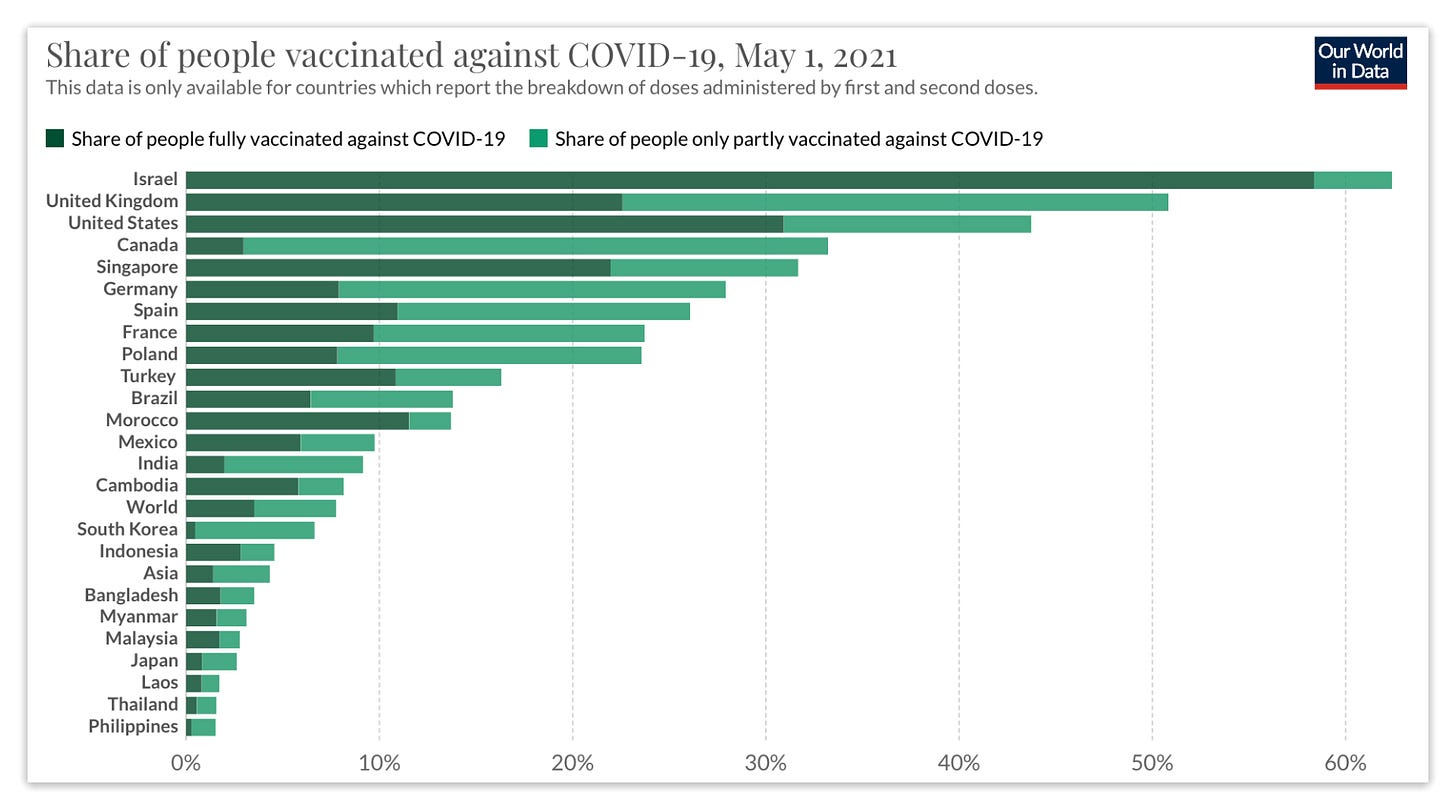

By the end of April the daily rate of new infections was above 2,000 but hardly any Thais had been vaccinated, and the launch of the country’s mass inoculation programme was still weeks away because Siam Bioscience was not ready to supply any doses. This chart shows how far Thailand had fallen behind the global and Asian average and even failing states like Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia by May 1.

In a televised speech on April 16, Prayut defended his decision not to order a national lockdown ahead of Songkran:

My heart aches every time we need to roll out these measures. I feel a heavy heart and uncomfortable because I know that these measures will affect someone to some extent, particularly low-income earners.

In a sign of how little attention had been paid to the possibility of seeking doses from alternative sources to AstraZeneca, Prayut was unable to even pronounce the names of leading vaccines.

In further remarks on April 20, Prayut admitted that the government had previously not been in a hurry to secure multiple kinds of vaccine from several sources because the they thought they had the coronavirus under control: “Initially, the purchases Thailand made were based on the situation at that time, when we were successful in containing the outbreak.” He also tried to claim that the regime had been wary of buying untested vaccines out of concern for the safety of the population:

Let me be clear. It's not that we acted too late or too little. Everything depends on the situation at a given time. We didn't want to subject people to risk when the vaccine was first produced.

This was another lie. They had moved slowly not because they had safety concerns, but because they wanted to wait for the royal vaccine, and as a result the third wave of the virus was spreading unchecked throughout Thailand.

The regime was forced to order millions more doses of Sinovac than originally planned, and by May the government was getting so desperate that it announced plans to squeeze two extra doses out of every bottle of AstraZeneca vaccine it acquired, to stretch the amount to 12 doses rather than 10. Meanwhile, there were tens of thousands of new infections as the virus spread through Thailand’s prison system.

Any hopes of using the vaccine produced by Siam Bioscience to glorify the monarchy were in ruins by now. It was glaringly apparent that the delay in starting mass vaccinations in Thailand, due to the months needed to build a production facility for the AstraZeneca vaccine, had been a calamity. The priority now for the palace was damage limitation, trying to distance the monarchy from the debacle.

This was when Chulabhorn launched her dramatic intervention. Although the government was not informed in advance, it’s inconceivable she would have gone ahead without permission from Vajiralongkorn. It was a smart strategic move, signalling the displeasure of the palace at the incompetence of the regime, making it appear that the monarchy was on the side of the people, and distracting attention from the Siam Bioscience fiasco.

The original plan for a royal vaccine had been a disaster, but Chulabhorn’s intervention allowed the palace to pretend that it was indeed working hard to get Thais inoculated as quickly as possible, and doing it much more effectively than the hapless government.

By June, Siam Bioscience was finally ready to get started. In a bizarre ceremony on June 2 with no journalists invited, the company announced the official launch of vaccine production in Thailand. Because the issue had become so toxic for the monarchy, there was no mention of the king and no royal portraits at the ceremony, although Vajiralongkorn’s top aide Satitpong was there, and so was Madam Pang, who gave a speech to a mostly empty room.

Epitomising the dishonesty and lack of transparency that had tainted the whole project from the start, the company released images of Satitpong and Teague that had been clumsily manipulated to add a fake sign declaring: “First batch of COVID-19 vaccine delivered by Siam Bioscience to AstraZeneca.”

Siam Bioscience said it had delivered the first batch of 1.8 million doses to the government and more would be dispatched later in the month, with a total of six million doses promised in June. The company released images of trucks leaving the production plant with the slogan “Made in Thailand for Thailand and southeast Asia” on their sides, but there was no overt royal branding at all.

More dishonesty later emerged when it transpired that production at Siam Bioscience was behind schedule and doses had to be imported from South Korea to meet the promised quota for Thailand in June.

On June 7, in a ceremony at Bang Sue Grand Station, Prayut announced the launch of Thailand’s mass inoculation drive — months after it should have begun. The prime minister insisted there would enough vaccines to inoculate everybody, and Anutin proclaimed: “The people will be vaccinated with covid-19 vaccines, one and all, and with speed and utmost safety.”

This was the moment the government had been hoping to use to unveil a royal vaccine with great fanfare, but the events of the previous few months had scuppered that idea. Prayut wasn’t even able to focus on promoting the Thai-made AstraZeneca vaccine, because most people were still getting inoculated with Sinovac so he had to give the Chinese vaccine equal prominence in the ceremony.

It took just a week for the mass vaccination programme to go off the rails. By mid-June hospitals and inoculation centres all over the country were cancelling appointments because of a shortage of doses. The main problem was that deliveries from Siam Bioscience were arriving later than scheduled. The royal vaccine was becoming even more of an embarrassment.

The regime rushed to order vaccines from other sources including Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson and Johnson — something they should have been doing at least six months earlier. But most of the doses ordered won’t arrive until late 2021 at the earliest.

The government failed to organise any kind of system to ensure the most vulnerable were vaccinated first. In the scramble for the inadequate number of doses available, state agencies and private companies were able to jump the queue, while many elderly people and those with serious health conditions were left with no access to vaccines.

Despite the chaos, the number of new daily infections in the third wave appeared to be falling. On June 11 there were 2,290 new cases, the lowest for a month. This emboldened Prayut to make a bizarre speech five days later, on June 16, which showed he had no understanding of the situation.

He claimed Thailand had signed contracts to receive 105.5 million vaccine doses in 2021 — four times the amount his government had been planning in late 2020 — and said more than 10 million Thais would be vaccinated each month from July onwards. And he made an extraordinary vow to reopen the country:

The time has now come for us to look ahead and set a date for when we can fully open our country and start receiving visitors, because reopening the country is one of the important ways to start reducing the enormous suffering of people who have lost their ability to earn income. I am, therefore, setting a goal for us to be able to declare Thailand fully open within 120 days from today, and for tourism centres that are ready, to do so even faster.

Even as he spoke these words, his rash promise was already doomed. Daily coronavirus cases were steadily rising again, because the fearsome Delta variant, which first emerged in India, had arrived in Thailand. It is the most dangerous and transmissible mutation of the virus so far, and the kingdom had no defences in place to contain it. It was first detected in April at a construction site in Laksi in Bangkok and has since spread throughout the kingdom in a devastating fourth wave that dwarfs anything Thailand had faced earlier in the pandemic.

A wealth of empirical evidence suggests the Chinese vaccines Sinovac and Sinopharm have limited effectiveness against the Delta variant. In Thailand, more than 600 medical workers who were double-jabbed with Sinovac have still become infected. Indonesia and Malaysia are in crisis too largely because of their reliance on Chinese vaccines. Even the AstraZeneca vaccine struggles against the Delta variant. The evidence suggests the mRNA vaccines produced by Pfizer and Moderna do much better.

Prayut’s promise of 10 million doses a month was another lie. The Thai regime appears to have believed that AstraZeneca would deliver all the 61 million doses ordered by the end of 2021, but officials have since admitted no timeframe was specified in the contact. AstraZeneca says Siam Bioscience can provide Thailand with five to six million doses a month, and the order of 61 million doses is unlikely to be completed until May 2022.

This provoked a furious reaction from Anutin, who demanded 10 million doses a month from AstraZeneca in a letter that has also been leaked. The Thai regime also threatened to impose export controls, but it’s probable this is just a bluff — will they really deny ASEAN neighbours like Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam the vaccine doses they have ordered, just to cover up their own mistakes?

The deteriorating relations between the Thai regime and AstraZeneca, due to the failure of Siam Bioscience to produce enough doses, are another consequence of the quixotic quest for a royal vaccine that has backfired so badly for Thailand.

The regime has at last agreed to join the COVAX programme, after many wasted months. Nakorn Premsri at the National Vaccine Institute pathetically tried to claim that the events of this year could not have been forecast, and made a belated apology for the government’s incompetence:

I apologise to the people that the National Vaccine Institute has not managed to procure a sufficient amount of vaccines for the unforeseen situation, although we have tried our best. The mutations were something that could not be predicted, which have caused a more rapid spread than last year. The vaccine procurement effort did not match the situation.

But it’s too little, far too late. Daily new infections in Thailand are now above 15,000 and the kingdom is staring into the abyss.

The palace continues to make clumsy efforts to exploit the crisis and pretend the royals are doing their best to help.

Last month they released a new set of propaganda photographs allegedly showing Vajiralongkorn and his official consort Sineenat “Koi” Wongvajirabhakdi working hard in the kitchens of Amphorn Sathan Palace to cook food for medical workers treating coronavirus patients. As usual, the pair were dressed in matching outfits — tracksuits, aprons (some with the slogan “so cute”) and even chef’s hats. There was no sign of Queen Suthida.

There were several odd things about the images. Vajiralongkorn’s eyes were closed in every single photograph. The pictures appear to be heavily manipulated — the king’s skin looks silky smooth with not a wrinkle to be seen. And one image shows what appear to be misshapen royal toes.

Of course, the notoriously lazy Vajiralongkorn wasn’t really doing any cooking — the photos were just staged. Ironically, they were released just a day after Prawit Wongsuwan demanded yet again that officials crack down on fake news.

It’s unlikely that Prayut and his government will survive the scandal of their catastrophic coronavirus strategy. Although they have always bent over backwards to promote the monarchy — and this is the main reason Thailand’s vaccine policy was such a disaster — the palace will show no gratitude or loyalty in return. As Chulabhorn’s intervention showed, the royals are already trying to distance themselves from the mistakes of the government. It’s probable that at the opportune moment, the palace will pull the plug on Prayut’s desperately unpopular regime, and install an even more authoritarian government in its place.

Meanwhile, as the regime keeps lying, Thais will keep dying.

I hesitate to "like" such dire stories as this one. I feel unbelievable sadness for my many friends in Thailand and the wonderful Thai people who should expect better governance than this and who remain at extreme risk with each new variant. As the US is learning the sad lesson the only real way to get this virus finally under control is to be sure the people are vaccinated with doses that are effective against it.

What really strikes me is that Bhumipol's amateur economic theory "Sufficiency Economy" played a role in this disaster. I was once all impressed with the same book that inspired Bhumipol: "Small is Beautiful." I think I was in high school. By early adulthood, I had heard the counter-arguments and regarded the book as well-intentioned nonsense. But around Bhumipol, no one was allowed to challenge the philosophy of "Sufficiency Economy"; on the contrary, what should have been a passing phase in his intellectual thought became official unquestionable policy. Look at the extent of the disaster from humoring him and not challenging the nonsense.