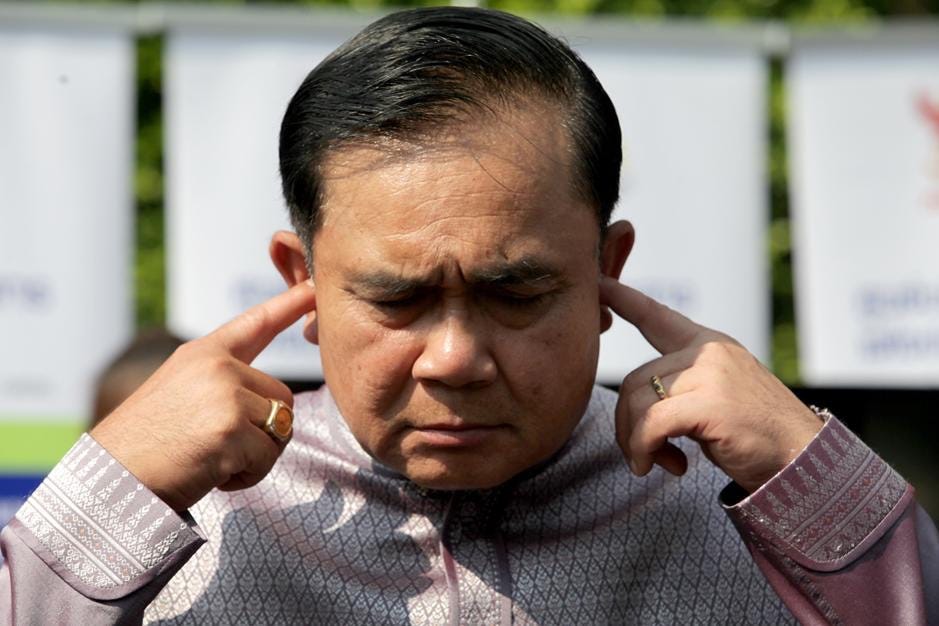

Time up for Prayut?

Also in this edition: arch-enemies Palang Pracharat and Pheu Thai team up to scupper electoral rule changes favouring smaller parties

Welcome to the latest Secret Siam news roundup. As usual, regular news updates remain free for everybody to read, but premium content and analysis on Thai politics and history are for paying subscribers. Secret Siam is fully funded by readers so if you find my work useful please consider contributing, it’s just $5 a month, or less if you pay annually.

This week’s newsletter focuses on recent developments surrounding the future of Prayut Chan-ocha and the rules for the upcoming elections next year…

Time bomb

The clock is ticking for Prayut Chan-ocha.

Opposition parties are petitioning the Constitutional Court to make a formal ruling on whether the prime minister’s term in office should end later this month on August 24. The tiny Thai Civilized microparty lodged its petition yesterday, and all the main opposition parties are expected to follow suit tomorrow, August 17. Although it is notoriously glacial in making decisions even by the sluggish standards of the Thai judiciary, in theory if the court accepts the petition it has a duty to issue an injunction suspending Prayut from office right away for as long as it takes for a formal decision to be made.

There are two key articles in the 2017 constitution that are at the heart of the dispute.

The first is Article 158. It includes this provision (the English wording is taken from an excellent translation provided by Constitute):

The Prime Minister shall not hold office for more than eight years in total, whether or not holding consecutive term. However, it shall not include the period during which the Prime Minister carries out duties after vacating office.

Prayut officially became prime minister on August 24, 2014, three months after he seized power in a coup. So this means his time should be up later this month.

As the leader of Pheu Thai, Cholnan Srikaew, said earlier this week:

According to the charter, a prime minister cannot stay in power for more than 8 years, no matter if the terms were consecutive or nonconsecutive. The issue that the term limit can be nonconsecutive was important because it meant that the term can be counted backward and there was no written exception to this rule.

According to Move Forward Party deputy leader Natthawut Buaprathum:

A time bomb may explode if general Prayut refuses to step down in a timely manner.

Prayut’s supporters are trying to argue that his eight years as prime minister officially began in April 2017, when the latest constitution was promulgated, or even in June 2019, when he was sworn in as premier following the elections earlier that year.

However, these arguments are undermined by Article 264, which basically says that ministers who were appointed under previous constitutions since 2014 were eligible to remain in these positions under the new constitution. Essentially, Article 264 was intended to codify continuity between the pre- and-post 2017 administrations, which is exactly what Prayut’s supporters are now trying to deny. They are trying to say he wasn’t officially prime minister before 2017 under the latest constitution, even though the constitution explicitly states that he was.

Moreover, documents shared on social media by Kanchanee Walayasevi, leader of the Peace-Loving Thais group, show that the Constitution Drafting Committee discussed this specific issue on September 7, 2018, and concluded that “even though the premiership started before the charter came into effect, the period should be counted as a premiership term”.

It’s particularly ironic because the eight-year limit for the prime minister was added to the constitution by the royalist and military elite to prevent another populist premier like Thaksin Shinawatra gaining political dominance via repeated elected victories, but now it has backfired to put Prayut’s future in doubt.

As usual in Thailand, however, whatever the Constitutional Court decides won’t be based on any sensible consideration of what the law actually says. The judges of the court have a long and dishonourable record of doing whatever whatever the palace and ruling elite tell them to do, and then coming up with various excuses to justify their decisions, however ridiculous and implausible.

The lack of basic principles of fairness and impartiality in the decisions of the Thai judiciary is so obvious by now that it doesn’t really require elaborating, but another recent development just demonstrated it once again. Earlier this month, Supreme Court judge Wichit Leethamchayo was denied an extension of his tenure because he allegedly mingled with and chatted to pro-democracy protesters a couple of times last year. This supposedly demonstrated unacceptable political bias, but Methinee Chalothorn, who was appointed head of the Supreme Court a couple of years ago and retired last year, had openly supported the ultraroyalist street protests trying to bring down the elected government of Yingluck Shinawatra but never faced any sanction.

So we know the Constitutional Court is not impartial and the judges will do what they are told. The question is whether King Vajiralongkorn and his allies still support Prayut and want to keep him in place at least until the next general elections in 2023.

This is where it gets interesting, because it has become clear even to many of the biggest fans of the irascible premier that he has become an electoral liability and that Pheu Thai and other opposition parties are heading for a landslide victory unless the regime can find a prime ministerial candidate who can mobilise much more support.

Moreover, Prayut has never been particularly close to Vajiralongkorn, unlike another former army commander-in-chief, Apirat Kongsompong, a firm ally of the king, who is widely regarded as a palace favourite for the role of prime minister in the future.

Under the constitution, Apirat becomes eligible for political office from October this year, two years after his official retirement from the military.

Prayut’s two sidekicks in the ruling triumvirate nicknamed the “three Ps” — Prawit “Pom” Wongsuwan and Anupong “Poh” Paochinda — have insisted the prime minister retains their full support. At Prawit’s 77th birthday party last week at the headquarters of the Five Provinces Bordering Forest Preservation Foundation, which is the engine of the elderly former general’s sprawling patronage and influence network, based inside the 1st Infantry Regiment compound on Vibhavadi Rangsit Road, the three old comrades put on an ostentatious performance of solidarity.

Anupong insisted that if Prayut leaves politics, the two other Ps will leave too. Prayut gave Prawit a framed picture of a cockeral as a gift, allegedly a reference to his old buddy’s Chinese zodiac sign. Prawit put his arm around Anupong’s waist as they had their photographs taken, declaring: “See, no fights among us.”

Of course this was all just posturing. Prawit’s has been increasingly in conflict with his two former subordinates in the 21st Infantry Regiment for several years. He is a brilliant networker and political pragmatist who wants to ensure his continued influence behind the scenes through his foundation. Obviously he has zero genuine interest in preserving any forests but he is determined to remain a key player in the elite, and the money funnelled through his foundation is essential for him to do that. Maintaining his network also requires him to do his best to help the Palang Pracharat Party, which he leads, get as good a result as possible at the next election.

Prawit’s rift with Prayut and Anupong exploded into the open last August and September when he gave tacit approval for his former henchman Thamanat Prompow, a convicted drug smuggler and serial liar, to launch a plot to topple his former comrades. Even after the conspiracy collapsed he continued to support Thamanat until his erstwhile political fixer’s behaviour became too mercurial and provocative ahead of the most recent no-confidence debate in parliament last month.

Prawit is increasingly geriatric and even he himself probably doesn’t believe that he is a credible prime ministerial candidate for the next election, but he has pointedly refused to rule it out, and if he could become the stand-in premier in the meantime if Prayut is suspended, it would give him immense leverage to boost his influence and network even further.

Another supposed ally of Prayut also seeking to benefit from the latest shenanigans is Bhumjai Thai leader Anutin Charnvirakul, who has long held aspirations to be prime minister, and is waiting to pounce. He says he will wait for the Constitutional Court decision, adding unconvincingly: “We will just follow the rules of the game.”

Prayut has no real influence over the military any more, since Vajiralongkorn became king and Apirat became the main palace protégé. His electoral appeal is imploding. He doesn't even have a major political party that unequivocally backs him, because most Palang Pracharat MPs think he is a liability and want him gone, so he’s having to scheme to create backup parties, which I’ll discuss later in this newsletter. The extraordinary popularity of Bangkok governor Chadchart Sittipunt starkly contrasts with the widespread national exasperation with Prayut. Even the ultraroyalists think he should be kicked out. He is a dinosaur facing extinction.

Former ambassador Pithaya Pookaman provided a useful analysis at Asia Sentinel:

Any prime minister, be he military or civilian, can be toppled if not on the same page with the palace… Prayut has served the palace well by providing lavish funds and amenities for the king and members of the royal family while safeguarding the monarchy by ruthless application of the country’s anti lèse majesté law, considered the world’s most severe. But Prayut’s eight years as head of government may be viewed by the palace as too long. Notwithstanding the favors he has showered on the king, his statecraft and performance have been an utter failure. Members of his family and his cronies have enriched themselves and occupied important positions in the country.

But the question for Vajiralongkorn and his allies in the palace, and the ascendant King’s Guard 904 faction of the military that has eclipsed Prayut’s clique, is when to pull the trigger.

Thai GDP seems to be on an upward trajectory as tourism recovers following the easing of more than two years of painful coronavirus travel restrictions, but other huge problems are looming as the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine sends fuel prices and the cost of living sharply higher, and the rebound in economic growth was lower than expected.

So should the palace jettison Prayut now, hope to ride an economic upswing to secure an unexpected election victory for pro-regime parties next year, and try to instal Apirat as prime minister? Or allow Prayut to waddle onwards as a lame duck premier until the polls, wait in the wings for a while in the hope that Pheu Thai support evaporates amid continued hardship, and stage another intervention to bring down yet another elected government in a couple of years and instal their candidate then?

These are the calculations being considered by royal advisors right now. One thing we know for sure is that whatever the Constitutional Court decides will have nothing to do with a fair interpretation of the charter. It will be determined by a signal from the palace based on the monarchy’s strategic calculation on how best to ensure that the regime wins in the end.

Party time

With a general election due in the first half of next year, all kinds of political shenanigans are already in full swing to bend the rules as much as possible.

One of the main issues preoccupying Thai politicians over recent months — when their time might have been better spent considering the worsening cost of living crisis, rising geopolitical tensions, and of course the unprecedentedly widespread demands for reform of the monarchy and achieving real democracy — is the method for calculating the distribution of party list MPs.

This is quite an esoteric subject but for those who have not been following it closely, here is my best attempt to explain it.

Party list MPs were first introduced in Thailand in the constitution of 1997, which was probably the most democratic charter the kingdom has ever had, even though it was still far from being fully democratic by any normal international standards. It was mainly created by two “royal liberals” who were close to King Bhumibol — Anand Panyarachun and Prawase Wasi. Their main motivation was to try to usher in a political system that would withstand the accession of Vajiralongkorn and replace the “network monarchy” of the latter decades of the Bhumibol era with a more formal rule-based order that could cope with the mercurial whims of Rama X.

The 1997 constitution was torn up after the military coup of 2006. Anand, who had been the main architect of the charter, was among those most responsible for wrecking it, as the royal liberals, like most of the monarchist elite, became obsessed with the threat they believed Thaksin Shinawatra posed to the traditional hierarchy. The rise and fall of the 1997 charter is a really interesting story which I will tell in full in a future newsletter, but right now I will just focus on one issue — party list MPs.

Patrician royalists and technocrats had long fretted that one of the issues blighting Thai politics was that that winning a seat in parliament usually required having an extensive vote-buying, patronage and intimidation network, so the system tended to favour local criminals, gangsters and so-called godfathers. The elite blamed ordinary Thais for this, for being too uneducated to vote for “good people”, even though there is extensive evidence that over recent decades Thais even in the least developed provinces increasingly vote for the party that they think will provide the best policies to improve their lives. But it remains true that even today, corrupt wealthy godfathers still dominate elections at the constituency level, and local politics is a brutal game that the self-proclaimed “good people” are unequipped to play.

Instead of really trying to reform the system, the elite continue to blame Thais for being too poorly educated to vote for the right people. Meanwhile they shamelessly also continued to exploit support from local politicians who bribe and fight their way into office.

The party list was created in the 1997 constitution as a way for “good people” who didn’t want to get their hands dirty in the rough-and-tumble of Thai electoral politics to still get into parliament.

The idea was simple (in theory) — around a fifth of seats in parliament (the number has changed slightly through various subsequent provisional and official constitutions) would be reserved for people who didn’t want to have to get involved in scrapping for a constituency. Each party would provide a list of proposed list MPs, who would be chosen in the order of preference their party specified, depending on the national vote their party received.

It wasn’t a terrible idea, but it was spectacularly abused after the 2019 elections, in which the Election Commission, which by now had become totally coopted by the royalist elite, chose a bizarre formula for calculating the party list seats which meant that several microparties which were just corrupt clients of the elite received a foothold in parliament while the main opposition party Pheu Thai received no party list seats at all. The progressive Future Forward Party actually did much better under the crooked calculation, and the regime tried to fix that problem by getting the Constitutional Court to dissolve the party in February 2020. It turned out to be a massive miscalculation that was one of the main triggers of the historic mass pro-democracy protests that have transformed Thailand forever. You can read a full account of the extraordinary events of 2020 here.

Some elements of the ruling elite were planning to try similar chicanery in the next election. Under the latest constitution, there will be 100 party list MPs from 2023 onwards, so the obvious way to calculate party list distribution would be to divide the number of national votes for each party by 100, and award seats on that basis.

But this would mean that microparties would be mostly wiped out, which of course has infuriated them, and many members of the elite — including Prayut — are so worried about the prospect of a Pheu Thai landslide victory that they are willing to do anything to stop it, even if it means damaging the prospects of Palang Pracharat too. So a bizarre formula was proposed in which the national vote of each party would be divided by 500 — the total number of seats in parliament to allocate party list MPs. It would ensure microparties could continue to thrive while reducing the power of the biggest parties.

Prayut was willing to harm the electoral prospects of Palang Pracharat if it damaged Pheu Thai even more. But most Palang Pracharat MPs rebelled over this idea, and it caused yet another rift between Prayut and his sidekick Prawit, who is the leader of the party. So Palang Pracharat and its nemesis Pheu Thai conspired to repeatedly ensure not enough MPs turned up in parliament to create a quorum.

Earlier this week, on August 15, after yet another parliamentary debacle presided over by the hapless octogenarian speaker Chuan Leekpai, the proposal lapsed after most Palang Pracharat and Pheu Thai MPs, and many unelected senators, once again avoided showing up in parliament. Barring another twist in this saga, the big parties have won, which makes it more likely than ever that Pheu Thai will be by far the biggest party in the next parliament and might even secure an absolute majority (although that doesn’t take into account the 250 elected senators who have a vote on the next prime minister too, another issue I’ll analyse soon).

As Thai PBS observed:

Political analysists see the killing of the bill as another political game that serves no public interest. Palang Pracharath, the core ruling coalition party, had earlier supported the bill with the hope that it would need support from small parties in the next general elections. Votes from the small parties were crucial in helping Prime Minister Prayut Chan-ocha and members of the Cabinet survive the recent no-confidence vote.

The whole saga has shown yet again that despite their claims of unity, divisions are growing between Prayut and Prawit.

Meanwhile, pointless political parties have been springing up like mushrooms, although many of them were created to take advantage of the 500-based party list formula and will wither unless the reversion to the 100-based calculation is challenged.

Probably the most ludicrous of all the new parties is Thoet Thai, a political vehicle for the disgraced Seksakol Atthawong, aka Rambo Isaan, a former Red Shirt and chronic political turncoat who switched sides to support the junta after the 2014 coup, and was even given a job as deputy minister in the prime minister’s office. He had to resign in April after a leaked audio recording showed he had accepted bribes from people involved in corruption in the national lottery. Rambo’s excuse that he had just been joking on the phone call was so pathetic that it stretched the bounds of credulity even beyond the breaking point of the current administration, so he was pushed out of the government. This new party is intended to somehow rehabilitate him.

Another cartoonishly corrupt figure — Thamanat Prompow, who was previously deputy agriculture minister, Palang Pracharat secretary general, and Prawit’s political fixer — took over the Setthakij Thai aka Thai Economic party in January after his antics seeking to undermine Prayut became so provocative that Prawit could no longer publicly be associated with him. To try to control his increasingly deranged former henchman, Prawit installed another ally, the sinister retired general Vit Thephasdin Na Ayutthaya, as head of Setthakij Thai, while Thamanat took the post of secretary general. But on May 24, Thamanat staged a coup in the party, resigning along with 14 others from the 22-member executive board to trigger the replacement of Vit as leader. Thamanat duly became leader, staged another botched plot to topple Prayut at the no-confidence debate last month, and then completely burned his bridges with Prawit by leaking documents showing illegal payments to microparties.

It’s not clear what Thamanat now hopes to achieve with his Thai Economic party, which has nobody who possesses any economic expertise, no coherent economic policies at all, and indeed no credible policy platform whatsoever.

After being ousted from Thamanat’s doomed political vehicle, general Vit jumped ship to another microparty with no policies, the Palang Chart Thai Party, now renamed Ruam Phaen Din, or Thailand Together.

It’s obvious to everybody that the sole purpose of this party is to assist Palang Pracharat in promoting the political interests of Prawit, especially if his rift with Prayut widens. But Vit has been unconvincingly trying to deny this, claiming he “has nothing to do with the PPRP” even though he was its strategy chief until January.

Perhaps the most interesting of the latest batch of new political parties is Ruam Thai Sarng Chart, which was initially founded by Rambo Isan before the lottery scandal forced him to resign, and has now been taken over by a group of ultraroyalist politicians who defected from the ossifying Democrats.

The party leader is Pirapan Salirathavibhaga, a former senior Democrat politician who broke away in 2019 to become an advisor to Prayut, and the secretary general is Akanat Promphan, stepson of the notorious Suthep Thaugsuban. Suthep was secretary general of the Democrat Party before resigning in 2013 to create the People's Committee for Absolute Democracy with the King as Head of State, the far-right royalist movement that sought to bring down Yingluck Shinawatra. Akanat, who famously (and untruthfully) claimed to have six degrees from Oxford University, was another key figure in that movement. Also joining the party is Witthaya Kaewparadai, who resigned as a deputy leader of the Democrats in April.

This party poses a real threat to the Democrats, who have always drawn their votes from two main areas — Bangkok, especially middle and upper-class voters, and southern Thailand where local godfathers affiliated to the party dominated elections.

The landslide victory of Chadchart in the Bangkok gubernatorial election, showed that the appeal of the Democrat brand has collapsed in the capital, and now Ruam Thai Sarng Chart says it will contest all southern seats in the next election which could do severe damage to Democrat prospects there. The Democrats are nicknamed “the cockroach party” because of their remarkable political resilience despite never coming close to winning general elections, but their prospects are looking increasingly bleak as their relevance evaporates.

Ruam Thai Sarng Chart is staunchly pro-Prayut and will back him as its prime ministerial candidate, although of course he denies it is his backup party if Prawit and Palang Pracharat stab him in the back.

All these machinations about the 500 calculation versus the 100 formula for picking the party list, and the proliferation of new parties with no ideology or policies, are almost comical, but also deeply depressing. It all shows how little Thai politics has evolved over multiple decades. It’s still just a game played by the elite “good people” and their criminal godfather allies to screw ordinary people.

More lèse majesté

The latest victim of the awful and archaic lèse majesté law is the dissident musician Parinya “Port” Cheewinkulpathom, who has been sentenced to nine years in jail, reduced to six because he cooperated with police, after being found guilty of three counts of violating Article 112. The charges relate to three Facebook posts he wrote in 2016, none of which made any mention of Bhumibol or Vajiralongkorn or any member of the royal family.

One post simply said that a monarchy that relies on using lèse majesté laws to protect itself is ignorant. The second, commenting on the abortive coup in Turkey in 2016, said it had failed because there was no king to endorse it. The third included profane lyrics for a song he was working on. None of the comments would be considered criminal in any country where democracy and freedom of speech are valued.

Port was one of the members of the brilliant political band Faiyen, whose members fled to Laos after the 2014 coup and then found themselves trapped and facing worsening danger as Thai refugees around Southeast Asia were murdered one by one by agents of the palace. In 2019, they managed to escape to asylum in France thanks to the tireless work of some Thai and foreign activists. Photographs shared on social media showed them on arrival in Paris, accompanied by Thai exiles Junya “Lek” Yimprachert and Jaran Ditapichai.

It was an extraordinary achievement to get the members of Faiyen to safety, but one element of the story was not quite true. Port was facing severe health problems and decided not to join the rest of the band in their escape. The person in the photograph holding up a sign that said “Port” was not actually him, it was just a ruse to throw the Thai authorities off his trail. While the rest of Faiyen escaped to Paris, Port went back to Thailand to be close to his family and try to fix his health issues. For a while it worked, but he was arrested last year, and now faces years in jail.

Amid the gloom, there is at least some good news — he was granted bail and his fight for freedom of speech continues.

In another piece of good news, the young activists Netiporn “Bung” Sanesangkhom and Nutthanit “Baipor” Duangmusit, who were on hunger strike for more than two months during their detention, and who I wrote about in my last news roundup, were at last given bail on August 4.

These small glimmers of hope show that the regime does not (yet) dare to launch a total crackdown on dissent, and that is a small reason to be hopeful.

That’s all for this edition, many thanks for reading and for following Secret Siam! 🙏

as always, a succint and comprehensive truth bomb from Andrew!

if the Thai people knew even a fraction of the truth(s) that this fearless journalist continues to explore and disseminate, they would rise up en masse and throw the entire corrupt lot out, including the obscenely greedy monarchy- but many Thais profit in one way or another from the entrenched corruption infesting all elements of Thai society from top to bottom...

Thanks Andrew, a superb report as always.

I sincerely hope you post these reports translated into Thai somewhere, for the Thai people to read.

They deserve to know and should be made aware of these awful details.

Please keep up the great work.