Wounded government survives no-confidence vote but limps towards electoral slaughter

The inside story of the shenanigans surrounding last week's debate in parliament, plus discussion of other interesting stories from the past seven days

Welcome to the latest Secret Siam news roundup. For those who may have missed it, I recently published a detailed reinvestigation of the notorious blue diamond saga that blighted relations between Thailand and Saudi Arabia for three decades. My main conclusion was that much of the story is based on lies and misinformation and the fabled diamond probably never even existed. I realise it sounds far-fetched that a gem that didn’t exist could be the cause of so much bloodshed and misery — I was surprised too when my research led me to this conclusion — but take a look at the evidence and judge for yourselves.

This week’s newsletter focuses heavily on the events surrounding last week’s no-confidence debate in parliament, plus a roundup of other news.

If you are not yet a subscriber and would like to get regular news roundups in your inbox you can sign up here:

Rattled regime gets another grilling — the inside story of the no-confidence debate

After four days of uncomfortable grilling by the opposition, prime minister Prayut Chan-ocha and his 10 targeted cabinet colleagues survived a no-confidence debate as expected, but the week’s events made it clearer than ever that the corrupt and divided ruling coalition is heading for defeat in the next national election which must be held by March next year at the latest. Prayut is becoming a lame duck premier whose allies are deserting him and whose days are numbered.

In Thailand, no-confidence debates are really just political theatre. Nobody ever expects anyone in government to lose a vote of confidence — this has never happened even once in the history of Thai parliamentary democracy. The purpose of the debate is not to actually bring down the government but to allow the opposition to ritually humiliate ministers by reciting a litany of accusations of corruption, incompetence and abuse of power, most of which are usually true. The role of the targeted ministers in the ritual is to just deny everything, however convincing the allegations against them.

The aim of the opposition is to rile their political adversaries, sow discord in the cabinet, which usually in Thailand is a ramshackle coalition of several fractious factions and parties, and undermine popular support for the government in the hope that they will suffer at the next general election.

In the latest no-confidence debate, the fourth Prayut has faced since he restored a highly skewed system of parliamentary democracy in 2019, five years after seizing power in a military coup in 2014, the real focus was on manoeuvring ahead of the next election, which must be held by March 2023.

The regime is seriously concerned that Pheu Thai will win a decisive victory next year, spooked by the stunning success of Chadchart Sittipunt in the Bangkok gubernatorial elections in May. Chadchart, who ran as an independent but was one of Pheu Thai’s three potential prime ministerial candidates at the last general election in 2019, won more than 50 percent of the vote to become Bangkok governor, the first time this has ever been achieved. Voting for the 50 members of the Bangkok Metropolitan Council followed the same trend — a remarkable shift away from the conservative pro-establishment parties who usually control the capital towards politicians perceived as progressive. Pheu Thai won 19 council seats and Move Forward got 14. The Democrats, who once dominated Bangkok, only won nine seats this time, and junta vehicle Palang Pracharat scored a desultory two.

If this trend is replicated at the next general election, it would be a disaster for Palang Pracharat and the Democrats, with Pheu Thai likely to perform extremely well and easily achieve a majority in parliament in coalition with Move Forward and some smaller opposition parties. The government is well aware of this, and panic and recriminations are reverberating through the ranks of the ruling parties. The economic climate, with Thailand yet to bounce back from the devastation wrought by the pandemic, and the cost of living rising at an unprecedented rate, will also impact support for the regime.

Their fear of losing is the reason why they made the absurd and unsupportable decision to calculate the allocation of party list MPs using a formula based on dividing votes by 500, which is the total number of members of parliament, rather than 100, which is the actual number of party list MPs. This is a similar tactic that the regime adopted after the 2019 election, and it is explicitly designed to deprive large parties like Pheu Thai of party list seats while rewarding numerous microparties which can easily be bribed. The threshold for getting a party list seat in the 500 formula is just a fifth of what it would be using 100 members for the calculation.

Even the staunchly pro-regime Bangkok Post columnist Veera Prateepchaikul says the decision is unjustifiable:

The change in the method of calculation is not just unthinkable, but also has no legal basis whatsoever. It defies common sense and is below the belt.

The most interesting element of the fiasco is that Palang Pracharat and the Democrat Party had initially supported using the 100-based calculation for the party list, because it benefits larger parties like them too. They changed their position to support the 500-based formula calculation because they are so worried about a huge Pheu Thai victory that they are willing to damage their own electoral prospects in the hope that it will damage Pheu Thai even more. Not surprisingly this has caused a rebellion among many of their own MPs, and Thai Enquirer reports that there is mounting talk of a U-turn that restores the 100 formula. The issue is likely to widen the rift between Prayut and the Palang Pracharat Party, because he supports using 500 for the formula to weaken Pheu Thai as much as possible even though it means fewer Palang Pracharat MPs will be elected.

Tensions between the prime minister and the party that propelled him to the premiership in 2019, and among the once-steadfast alliance of the so-called saam paw — the “three Ps”, Prayut, Prawit “Pom” Wonguwan, and Aunpong “Pok” Paochinda — are mounting as electoral disaster looms.

The three old comrades forged their alliance while serving in the 21st Infantry Regiment, became the leaders of the dominant faction in the army, and were the core of the junta that seized power in 2014. Prayut became prime minister but the “big brother” in the triumvirate is Prawit, who is nine years older than him and always outranked him in the army.

The first clear sign of cracks among the comrades was the drama of the previous no-confidence debate last September. Prawit’s notorious henchman and political fixer Thamanat Prompow, a cartoonishly corrupt political gangster with a fake PhD who spent four years in jail in Australia for smuggling heroin, was feverishly plotting to topple Prayut by persuading a faction of disgruntled Palang Pracharat MPs to vote against him. As part of the conspiracy, Thaksin Shinawatra was offered the possibility of amnesty if he agreed not to stand in the way of Prawit replacing Prayut. The plot unravelled when Prayut found out about it and launched a counteroffensive to save his premiership, forcing Prawit to pull the plug. You can read my full account of the saga here.

The main reason for the plotting was a conflict over control of the Ministry of Interior. Control of the ministry is seen as one of the biggest prizes in Thai politics, because it enables the incumbent party to exert control over the nationwide network of district chiefs, local officials and village headmen whose assistance can deliver millions of votes. It also offers awesome opportunities for embezzlement on an epic scale and dispensing patronage and bribes using taxpayer money. Anupong has been interior minister since the 2014 coup, but like Prayut he is not a member of Palang Pracharat and so the party has been cut off from all the opportunities that holding the ministry would provide. Thamanat, an inveterate schemer and master of the political dark arts, wanted Anupong replaced by a member of Palang Pracharat — ideally himself — and Prawit, who is leader of the party, agreed. But Anupong refused to budge from the position, and Prayut backed him. The three Ps had never been more divided.

Relations between Prayut and Prawit have been painfully awkward since September. Publicly they insist everything is fine. But everybody knows it’s inconceivable that Thamanat would have launched the plot without Prawit’s backing. Privately, Prayut is well aware that his “big brother” Prawit had planned to topple him and may well try to do so again at the opportune moment. Despite being prime minister, Prayut is isolated because Prawit controls Palang Pracharat and has been playing a double game.

Following the failed plot, Prayut fired Thamanat and another key Prawit ally, Narumon Pinyosinwat, for disloyalty, but Prawit pointedly allowed them to remain in their key roles in Palang Pracharat, as secretary-general and treasurer respectively. Prawit also appointed an old ally, the sinister retired general Vit Thephasdin Na Ayutthaya, as head of the Palang Pracharat strategy committee. Vit is notorious for his links to organised crime, and also has longstanding ties with Thaksin. Prawit was professing loyalty to Prayut but his actions regarding Palang Pracharat told a very different story.

Thamanat eventually left Palang Pracharat on January 19 this year along with 20 MPs loyal to him. The official story is that the party expelled him for making unreasonable demands. As usual when Palang Pracharat shenanigans are afoot, the question of whether to kick out Thamanat’s faction was discussed at a meeting at the plush headquarters of Prawit’s patronage machine, the Five Provinces Bordering Forest Preservation Foundation inside the 1st Infantry Regiment headquarters on Vibhavadi Rangsit Road, with the party’s 17 executive committee members and 61 of its MPs. Of the 78 people present, 63 voted to expel Thamanat’s renegade faction.

But the truth is that Thamanat engineered his own departure in collusion with Prawit. Palang Pracharat had just lost two by-elections, in Chumpon and Songkhla, on January 16. Allies of Prayut blamed Thamanat who had made ill-advised comments urging voters to choose candidates with the right family name and plenty of wealth, comments seized upon by the Democrats who won both seats. It was becoming increasingly difficult for Prawit to protect Thamanat in Palang Pratcharat given his open defiance of Prayut, and the gaffe ahead of the by-elections was the final straw. They both agreed it was time for Thamanat to leave the party, which would also enable him more freedom to challenge Prayut in future if Prawit’s plans required it.

If Thamanat and his allies had resigned from Palang Pracharat they would have ceased to be MPs, but because they were expelled by a meeting of executive committee members and MPs in which more than three quarters voted to kick them out, under Article 101 (9) of the constitution they were allowed to remain in parliament as long as they found another party within 30 days. Ahead of the vote, allies of Thamanat leaked information to Thai Enquirer stressing that he wanted to leave. Prawit was conspicuously silent about the whole episode and was not present when the votes were cast. He left it to deputy party leader Paiboon Nititawan to speak to the media about what had happened. The whole thing was just a charade, with Prawit pulling the strings behind the scenes as usual.

Sure enough, the expelled rebels took over the the Setthakij Thai aka Thai Economic party, which was essentially just an empty shell with no MPs, formed in 2020. In March, retired general Vit become party leader with Thamanat as secretary-general. But the pair soon clashed over strategy — Vit wanted the party to remain firmly part of the ruling coalition, while Thamanat wanted a more ambiguous stance to gain maximum leverage. Tensions between the two men worsened in May after Thamanat said he intended to have dinner with representatives of Pheu Thai and the so-called “Group of 16” bloc of MPs to discuss another potential bid to topple Prayut at the next no-confidence debate.

Somewhat confusingly, despite its name, the Group of 16 had up to 30 MPs by this stage — the representatives of all the microparties in the coalition plus some opportunistic rogue Palang Pracharat MPs led by Pichet Sathirachawal. As columnist Veera Prateepchaikul explained in the Bangkok Post, the group “has no fixed loyalty” and dances to the tune of the highest bidder:

The members are like mercenaries whose loyalty depends on which paymasters are offering them the most remuneration. For the past three-plus years in parliament, the group has barely done anything that could be called an achievement in their putative role as lawmakers. The only time they have a voice and are of value is when their votes can be the deciding factor, say for the passage of a financial bill or after a censure debate like the one on Saturday. For a government with only a slim majority in the Lower House, their votes are a godsend.

Thamanat has had close relations with the microparties for years because after the 2019 general election it was his job to bribe and cajole them to join the coalition, and to manage the relationship with them and keep them onside. He caused uproar among the microparty leaders in September 2019 with another of his frequent gaffes, when he compared his role to being a “monkey keeper” whose job was to “keep feeding them bananas all the time”. He mostly managed to salvage the situation by shovelling even more bribes to them. Throughout his time at Palang Pracharat he kept them well fed with metaphorical bananas.

Thamanat was a member of Pheu Thai before switching to Palang Pracharat in 2018, and has repeatedly refused to rule out returning to his former party. Sources say he is in relatively regular contact with Thaksin. Despite the failure of the conspiracy last September, Thamanat never gave up plotting to topple Prayut by persuading the microparties and rebel Palang Pracharat MPs to switch sides. The plan was for Prawit to become prime minister and Thamanat to get the interior ministry. Thamanat would orchestrate everything by ensuring enough defections, and Thaksin would be secretly promised an amnesty if he told Pheu Thai not to block Prawit becoming premier.

But Thamanat has repeatedly sabotaged himself due to his recklessness and chronic lack of subtlety. Even though Prawit supported his schemes from the sidelines, the deputy prime minister could not be seen openly plotting against his old comrade in the three Ps. Thamanat thought that loudly broadcasting his dinner date with Pheu Thai and the Group of 16 would give him the leverage to force Prayut to appoint him as interior minister, but his behaviour was just too provocative and Prayut told him to abandon the plan. Vit tried to rein him in too.

Thamanat was becoming increasingly unhinged and erratic as his plans fell apart. He was spiralling so far out of control that not even Prawit could handle him. On May 24, Thamanat staged a coup in the Setthakij Thai party, resigning along with 14 others from the 22-member executive board to trigger the replacement of Vit as leader. Thamanat had wanted to be party chief from the start, but had initially heeded Prawit’s advice to allow the more experienced and less volatile Vit take the role instead. Within two months that arrangement had already collapsed as Thamanat unravelled.

Thamanat formally became leader on June 10, and immediately declared that the party would not guarantee its support to any cabinet minister except Prawit in the no-confidence debate, saying: “To be honest, all of the ministers said to be the targets should have a cause for concern except general Prawit.” Not all his former allies were happy about the toppling of Vit, and Thamanat’s more combative approach, and the size of the Setthakij Thai bloc in parliament dwindled to 16 MPs.

Thamanat suffered another blow when Setthakij Thai was thrashed in a by-election in Lampang on July 10, more than 20,000 votes behind the winning candidate from the small opposition Seri Ruam Thai Party. His reputation as a brilliant — if exceptionally dodgy — political operator was built on the belief that he was superb at mobilising votes through whatever means necessary and delivering election victories against the odds. This was why his allies always forgave him for all his lies and crimes and recklessness — they believed he could deliver results. But suddenly faith in his abilities was starting to evaporate. His relationship with Prawit was strained, his winning touch had deserted him, and he was making one misjudgement after another.

Thamanat claimed his party had lost because of its affiliation with Prayut and the ruling coalition. The two Setthakij Thai MPs who had posts as government whips resigned on July 12, and Thamanat announced that the party was formally leaving the coalition and joining the opposition. He confirmed that Setthakij Thai would vote against all ministers except Prawit in the no-confidence debate.

Thamanat was gambling that his announcement would be a bombshell that would strike fear into Prayut and rally more disgruntled Palang Pracharat and microparty MPs to his side, so the opposition had a serious chance of pulling off a shock defeat of the government. But his antics increasingly reeked of desperation rather than careful calculation. As Erich Parpart wrote at Thai Enquirer, Thamanat “seems to be fumbling in every major decision he has been making ever since he quit the ruling coalition”. Olarn Thinbangtiew, a political scientist from Burapha University, told the Bangkok Post that Thamanat’s “actions have made him lose political credibility” and predicted more MPs would desert his faction. In comments to Thai PBS, Wanwichit Boonprong, a political science lecturer at Rangsit University, said:

His problem is that he is arrogant and overestimates his abilities. In fact, it was Prawit who gave him his power and charisma. That’s why he rose so fast to become a larger-than-life figure. He was given too much status.

Ahead of the debate, Thaksin made some deliberately provocative comments in one of his regular chats on the Clubhouse app, where he appears using the pseudonym Tony Woodsome. He said Chadchart’s landslide win in the Bangkok gubernatorial election could be a harbinger of a similar large victory for Pheu Thai in the general election next year. “I would like to warn that the next elections could be like what happened in Bangkok,” Thaksin declared, in an obvious attempt to goad the government.

On July 18, the day before the no-confidence debate was due to begin, Prawit held a meeting of Palang Pracharat MPs. He ordered all of them to vote for 11 ministers targeted in the debate. According to several sources who were there, as the meeting was drawing to a close, one member of the executive committee said there was widespread support for a cabinet reshuffle in which Anupong would be replaced by Prawit. At least five party MPs raised their hands to support the idea. Prawit tried to shut down the discussion, saying:

Well, it is an opinion. I'll talk to the prime minister about this, but right now everyone must vote for the premier and 10 cabinet ministers.

It was a clear signal that there is still significant discontent in Palang Pracharat that Anupong remains interior minister — discontent that Prawit shares.

When the debate began on Tuesday, July 19, it was clear that Prayut was still stewing about Thaksin’s comments on Clubhouse. The prime minister, who gave a typically blustering and self-pitying performance throughout the week, tried to attack Pheu Thai on the first day of the debate last Tuesday for not bringing Thaksin back to Thailand to fight the politically motivated corruption charges against him. In his response to Pheu Thai leader Cholnan Srikaew calling him an enemy of democracy, he bleated:

As the prime minister, I don't know everything. I am not good at everything. I am not someone you might say is the cleverest person. But where is he now? I know you may admire some people who previously held this position and praise them for doing a better job than me. That's fine. Just bring them back if you can.

In a response in his next Clubhouse chat, Thaksin gleefully twisted the knife, promising once again that he will return some day, and joking about his ability to live rent-free in Prayut’s head:

I'll come back for sure. I'll definitely come back… If he asks where I am, I'll say I'm always on his mind. When reporters ask him ... or when there is a parliament debate, I'm the first on his mind.

It’s remarkable that 14 years after Thaksin went into exile, and eight years after Yingluck was deposed in a coup, the regime continues to try to blame the Shinawatra clan for the kingdom’s problems.

One of the most intriguing episodes in the debate was on Wednesday, when Prawit was being grilled by Move Forward party-list MP Thiratchai Panthumat over alleged interference in the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) and Customs Department investigations into the infamous scandal that erupted when photographs showed he had a collection of more than 20 luxury watches worth millions of dollars which he never declared in mandatory asset statements and claimed he had borrowed from a friend who then conveniently died.

During his response to the allegations, Prawit denied having anything to do with the 2014 coup. “I give you the coup maker. Here he is,” declared Prawit, pointing at Prayut who proudly raised his hand in acknowledgement among much awkward laughter.

Prawit also denied that he was part of an alliance with Prayut and Anupong “Pok“ Paochinda, even though the so-called “three Ps” led the most powerful faction of the army for many years and have dominated Thai politics since the coup. According to Prawit:

I was not involved in the coup. Neither was Anupong… Only the prime minister staged it. I didn’t even know when it was planned. It’s rubbish to talk about the “three Ps” alliance.

Obviously this is totally untrue. All of the three Ps have frequently boasted that they are an unbreakable band of brothers who fought together in the army and then in politics for decades. Prawit was the main mastermind of the deep state conspiracy during 2013 and 2014 that eventually toppled Yingluck. What’s interesting is that he is now suddenly trying to distance himself from his old comrade Prayut. It was a further sign that support is ebbing away from the prime minister and that there are tensions among the three Ps.

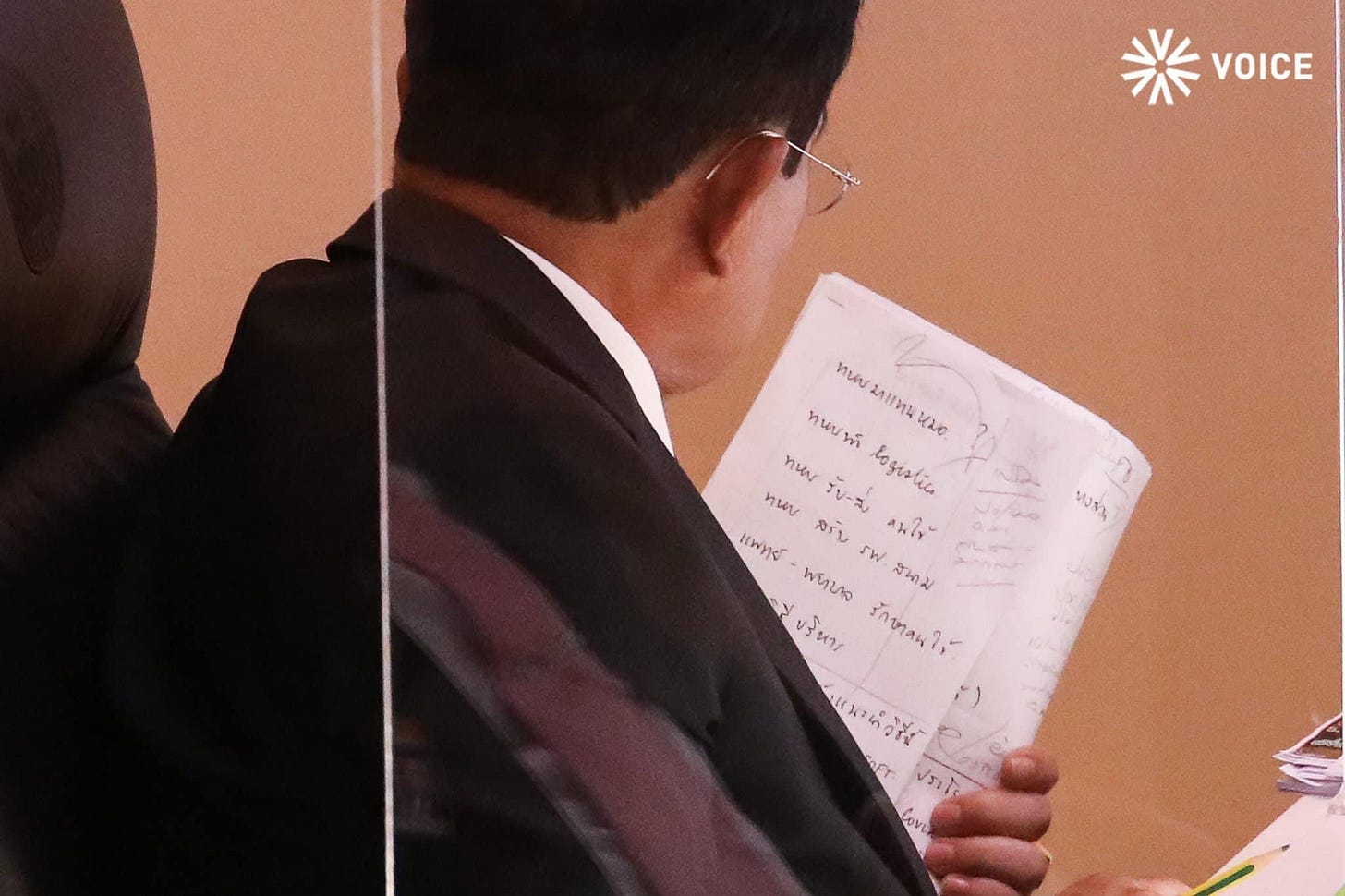

During the debate, Prayut was also photographed reading from some crudely written bullet points that appeared to claim the military had played a key role in coping with the coronavirus. He also insisted that the regime had been widely praised for its handling of the pandemic, even though its performance was actually a disaster.

As usual Move Forward MP Rangsiman Rome made a strong contribution, presenting significant new evidence of corruption in the police and military.

In Saturday’s vote, ministers had to win the support of more than half of parliament. Because there are currently only 477 MPs rather than the full complement of 500, this meant they needed 239 votes to survive.

As the vote approached, Thamanat was still trying to persuade others to vote against Prayut, but with no success. The Group of 16, who Thamanat had been trying to persuade to join him, announced they would support most ministers, except social development and human security minister Chuti Krairiksh of the Democrat Party and deputy finance minister Santi Promphat, who is also Palang Pracharat’s new secretary general. Both men faced highly credible and detailed allegations of corruption during the debate. So did labour minister Suchart Chomklin of Palang Pracharat who was accused of enriching himself with bribes paid to facilitate the import of migrant workers, and transport minister Saksayam Chidchob, brother of the notorious Newin, accused of concealing his ownership of a construction company that was awarded contracts worth more than a billion baht by his ministry.

Meanwhile, the Democrats were riven by internal disputes, with one faction urging MPs to vote against Chuti, and a rival faction threatening to vote against party leader Jurin Laksanawisit, the commerce minister, in retaliation.

The evening before the vote, Prawit met the members of the Group of 16 and urged them to vote for all 11 ministers facing censure. According to a leaked screenshot of a LINE chat that was circulated on social media, the MPs were offered 100,000 baht each as an inducement. By now it was clear that Thamanat had failed to get the numbers he needed to unseat any ministers. The government was safe.

When the votes were cast on Saturday, Prawit had by far the best score, with the most votes of support and least no-confidence votes of any minister. His outperformance was mainly due to the support of Thamanat’s Setthakij Thai faction, which was still pledging loyalty to Prawit. Also, Prawit is widely regarded as the most powerful player in the government, and nobody in the ruling coalition wants to annoy him.

Prayut was the fourth best performer, behind Prawit and the Bhumjai Thai duo of Anutin Charnvirakul and Saksayam Chidchob. It was striking that he had 12 fewer votes of support that Prawit, and 13 more votes of no-confidence.

At the bottom of the list was Democrat Party leader Jurin, who got just 241 votes of confidence, surviving by a margin of just three votes. The incessant infighting in the party was mainly to blame, plus the fact the Democrats are widely disliked by their coalition partners.

Anupong performed badly too, with only 245 votes of support and 212 votes of no-confidence. It was the highest number of no-confidence votes any of the ministers received. Six Palang Pracharat MPs, all from Samut Prakan, voted against him, along with the opposition and Thamanat’s faction. If Thamanat had managed to flip another seven coalition MPs, he would have toppled Anupong, and achieved what he wanted — a new interior minister. But he failed.

Here’s a Bangkok Post graphic showing the voting for all ministers.

All of Thamanat’s bluster and scheming had achieved nothing. He was enraged that the Group of 16, who he had been feeding “bananas” for years, in the form of large monthly payments during his time at Palang Pracharat, had failed to back him when he needed them. He decided to take revenge, regardless of the consequences.

A few hours after the vote, Thamanat leaked several LINE messages and banking receipts that appeared to show that the Group of 16 had not just accepted bribes ahead of Saturday’s vote, they had been receiving monthly payments for years. He shared screenshots of bank documents and LINE chats that showed some of the Group of 16 had been receiving payments of 100,000 baht a month for years.

It was no surprise to anybody that this faction of mercenary MPs had been paid regularly to secure their votes, but it was immensely embarrassing to the government and the corrupt politicians they were being to have everything exposed. Some of the Group of 16, such as Khathathep Techadejruangkul, leader of the Pheu Chart Thai Party, tried to claim the evidence was fabricated by Thamanat:

He wanted the Group of 16 to do his bidding and when he couldn't, he created a fuss. There are no facts and this is a fabrication of documents. Seniors are looking into this and it will end soon.

But the evidence is almost certainly genuine, not least because the person who leaked it — Thamanat — knows all about secret payments to microparties because he was the person responsible for agreeing the payments. The leaked documents also implicate Prawit, because the transactions were handled by his Five Provinces Bordering Forest Preservation Foundation. Thamanat’s reckless decision to get revenge on the “monkeys” he had been feeding with “bananas” for years didn’t just damage them — it damaged himself and Prawit too.

The bribes were a clear violation of anti-corruption rules which require MPs to declare any gift worth more than 3,000 baht. In theory, those implicated could face three years in jail, a fine of 60,000 baht, and a 10-year ban from politics. The royalist activist Srisuwan Janya, who relentlessly files complaints and lawsuits about corruption in politics, has pledged to petition the NACC about the scandal.

But there is little probability that the case will go anywhere — the pliant NACC and judiciary will ensure that no action is taken. Prawit says he is not worried and expects the NACC to clear him just as they did over the wristwatch scandal. “Let them take it up. It'll be like my watches case,” he said. “I'm not afraid.”

On Monday, Prawit went to Samut Prakan to meet the six rebel Palang Pracharat MPs who voted against Anupong in the debate. One of them, Krungsriwilai Sutinphuak, prostrated at Prawit’s feet as he arrived. Afterwards, as usual, Prawit declared that the dispute had been settled and everything was fine.

Prayut has insisted there will be no cabinet reshuffle. Anupong says he’s not worried about the pressure to remove him from the interior ministry:

If there should be a cabinet shake-up, it is up to the prime minister to decide. There's no reason to fear. No matter what changes may be in store, the fellowship between the “three P” generals will never break.

But in fact, the fellowship is already broken. Prayut and Anupong can’t trust Prawit, and it remains unclear if Palang Pracharat will even nominate Prayut as its prime ministerial candidate at the next election. He is deeply unpopular, in stark contrast to the rock star status enjoyed by Chadchart. He has no real political powerbase — he’s totally dependent on Prawit — and he no longer has any influence over the military. The rise of the democracy movement and mounting calls for reform of the monarchy have transformed the political landscape. Prayut is a dinosaur who is approaching extinction.

Thamanat has burned his bridges, and strained his alliance with his political patron Prawit. His erratic behaviour has driven away many of his supporters and his Setthakij Thai party has little hope of winning many seats at the general election.

Pheu Thai looks set to perform strongly, and although it will struggle to win an overall majority, particularly with the new party list calculation, it is likely to be able to form a coalition with Move Forward and some smaller parties. But this may lead to constitutional deadlock because the prime minister they propose has to be approved not just by parliament but also by the 250 appointed senators who are mostly virulently anti-Thaksin and hate Move Forward for alleged anti-monarchism. To form a workable government some kind of compromise will have to be found. Thaksin may have to accept an establishment candidate. It’s not even inconceivable that Prawit becomes prime minister — Move Forward would be highly unlikely to serve in a government led by him, but parties like Bhumjai Thai could be persuaded to join the coalition, and having Prawit at the helm would help reassure the old elite that Thaksin’s influence can be controlled. The alternative is a new bout of political instability as royalists and the military scheme to bring down the government.

But Prawit is already 76 and in visibly poor health. He struggles to even walk and has to be assisted by aides. If he ends up as prime minister it means more political stagnation for Thailand.

Thaksin is desperate to come home, and will be hoping that Pheu Thai win enough seats to give him leverage to secure a deal. He’s not really interested in progressive policies or reform, and is mainly just focused on himself and his family. He wants to be rehabilitated in Thailand before he dies.

On his birthday last Saturday, after the votes had been cast following the no-confidence debate, Thaksin spoke to Red Shirt supporters in Korat in a video call. Thaksin promised it would be the last birthday he spends outside Thailand.

“This year will be the last,” he told the cheering crowd. “See you all in Thailand next year.”

Extraordinary inhumanity

On the final day of the debate last Friday, Bencha Saengchan of the Move Forward Party gave a speech calling for the release of all political prisoners. As Thai PBS reported:

No one should be arrested or incarcerated for expressing a political opinion which differs from the government’s, especially a government which came to power as the result of a coup, said the opposition MP, adding that the first step towards political reconciliation in the country is to release these people.

As her speech drew to a close, Move Forward MPs held up pictures of detained activists Netiporn “Bung” Sanesangkhom and Nutthanit “Baipor” Duangmusit who have been denied bail despite facing severe health problems after more than eight weeks on hunger strike.

Netiporn, 26, and Nutthanit, 21, affiliated with activist group Thaluwang, which roughly means “break the palace”, held an event at Siam Paragon mall on February 8 surveying shoppers on their opinion about the disruption caused by royal motorcades, which are notorious for causing severe traffic disruption in Bangkok. Activists have held similar polls on royal issues around Bangkok this year, with passers-by invited to vote by placing coloured stickers under the statement they agree with.

At Siam Paragon, Netiporn and Nutthanit were obstructed and harassed several times by police and mall security guards, but several people at the mall managed to vote, all of whom agreed that royal motorcades cause problems. Siam Paragon is a particularly sensitive place for protests because it is part owned by the Crown Property Bureau and Princess Sirindhorn, and includes the flagship store of Princess Sirivannavari’s fashion brand.

After leaving the mall, the two women headed towards Sirindhorn’s residence Sra Pathum palace to deliver the results. They were blocked by police and their poll was ripped from their hands.

For having the effrontery to ask for people’s views on royal motorcades, Netiporn and Nutthanit were charged with lèse majesté, sedition and failure to comply with police orders. They were released on bail on the condition that they wore electronic ankle bracelets, avoid doing anything that might offend the monarchy, or organise any more protests.

But they held more public surveys — on land expropriation by the monarchy on March 13 at Victory Monument, on whether people wanted to pay taxes to maintain the monarchy on March 31 at the Ratchaprasong intersection, and on whether the king should be able to use his powers however he wishes on April 18 at Chatuchak MRT station.

On April 28 police raided their apartment and arrested them, and the Bangkok South Criminal Court formally revoked their bail on May 3. They have been detained at the Central Women’s Correctional Institution ever since.

Thaluwang activists have always argued — reasonably — that asking questions should not be a crime. Netiporn and Nutthanit began a hunger strike on June 2 in protest at their continued detention.

When they were brought to court on July 18 for a witness hearing, Nutthanit was so weak that she was unable to walk and could barely communicate. Her hands and legs were shaking and her nails were turning purple. During the hearing, Nutthanit lost consciousness. Netiporn complained of a severe stomach ache. Their lawyers asked for them to be transferred urgently to the nearest hospital, but prison officials tried to insist that they be taken to the Medical Correctional Institution. After a volunteer medic confirmed that they needed to see a doctor as soon as possible, the judge overruled the prison officials and they were sent to Lerdsin Hospital. Doctors there examined the women but declined to admit them to hospital, and they were transferred to the Medical Correctional Institution.

According to Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, as reported by Prachatai:

The two activists refused to be treated by the Medical Correctional Institution, so they were taken back to the Women Central Correctional Institution. Netiporn told her lawyer that Nutthanit had no energy, but they still had to undergo physical examination before going back to their cell. She said that four people were holding Nutthanit and taking off her clothes to examine her. Nutthanit also told her lawyer that she asked the prison officials not to take off her underwear because she was on her period, but they did anyway, causing blood stains all over her legs. She told the lawyer that she would like this to be reported as she does not wish to be repeatedly violated.

They spent Tuesday night at the prison infirmary… Other inmates working at the infirmary had to carry Nutthanit up to the second floor, and that her blood pressure was found to be lower than normal, even though doctors at Lerdsin Hospital said her blood pressure was normal.

Despite their condition, judge Santi Chukitsappaisan at the South Bangkok Criminal Court denied them bail on July 19, saying their health was normal.

It was an absurd and shockingly inhumane decision, and the regime is playing a very dangerous game. After more than eight weeks on hunger strike, Netiporn and Nutthanit are clearly extremely unwell, and there are concerns about how much longer they can survive. If a young woman whose only crime was asking questions about the monarchy dies in detention, there will be worldwide condemnation, and it could ignite a new wave of mass protests.

Spying on citizens

The regime’s use of the notorious Israeli spyware Pegasus to hack the mobile phones of pro-democracy Thai activists, academics and politicians was another major issue raised during last week’s debate.

Back in November last year, Apple warned several activists, academics and politicians that their phones had been hacked by “state-sponsored attackers”. The technology giant is fighting an escalating technological battle to protect the privacy of iPhone users against spyware, above all Pegasus, which was developed by Israeli company NSO and has been widely abused to target politicians and activists all over the world.

NSO claims it only sells the spyware to regimes that respect the rule of law, for legitimate operations targeting crime and terrorism, but there is overwhelming evidence they have provided it to numerous authoritarian regimes and dictatorships — including Thailand.

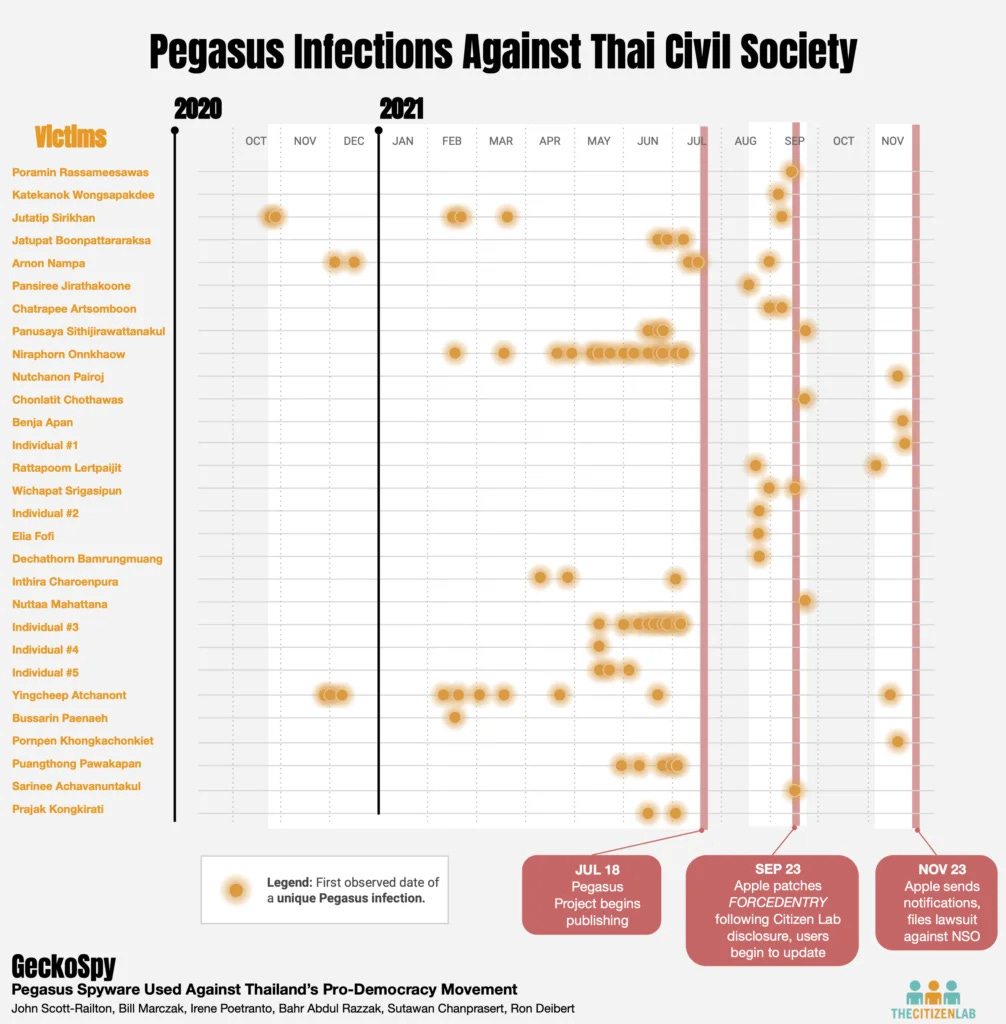

The Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto, which has developed cutting-edge expertise in detecting spyware on mobile phones, issued a report last week in collaboration with Thai NGOs iLaw and DigitalReach showing that at least 30 activists, academics and politicians had been targeted by Pegasus between October 2020 and November 2021. They provided a graphic showing those who had been affected:

The list includes many of the most prominent pro-democracy activists but the scale of the hacking is likely to be far larger than we know — as Citizen Lab’s John Scott-Railton noted, the revelations so far are likely to be just the “tip of the iceberg”. Many Thai activists and politicians including Rangsiman Rome and Move Forward leader Pita Limjaroenrat use Android phones, and it’s not currently possible to detect if these devices have been compromised by Pegasus.

During the no-confidence debate, Move Forward MP Phicharn Chaowapatanawong said five more hacking victims had already been discovered — his Move Forward colleagues Bencha Saengchantra, Chaithawat Tulathon and Pakorn Areekul, as well as Pannika Wanich and Piyabutr Saengkanokkul who were founding members of the Future Forward Party and after being banned from politics after the regime disbanded the party are now leaders of the Progressive Movement.

The Royal Thai Police have formally denied using Pegasus spyware to hack the phones of democracy activists. Deputy police spokesman colonel Kissana Phathanacharoen declared:

The Royal Thai Police have never used any spyware to violate anyone’s rights as suggested in those news reports and rumours spread on social media. The RTP strictly follow laws and regulations.

But during the debate on Tuesday, Chaiwut Thanakamanusorn, the minister of digital economy and society, admitted for the first time that the Thai regime uses spyware to “listen into or access a mobile phone to view the screen, monitor conversations and messages”. But interestingly, according to the Reuters report on his comments, “he added his ministry does not have the legal authority to use such software and did not specify which government agency does”.

This admission clearly got him into trouble because on Friday he comically tried to deny saying things that he clearly had said. He claimed he had just stated he knew that Pegasus existed and was used by some countries around the world, but had never said it was used by Thailand, declaring: “I said I knew of a system that is used for security and drug suppression but I did not say that it existed in the Thai government.” To make Chaiwat’s week even worse, he was also publicly accused of marital infidelity during the debate.

Prayut denied having any knowledge of the spyware, saying: “Regarding Pegasus, I don't know about it. You always say I’m not smart. I have no need to spy.

All these denials are of course absurd — there is incontrovertible evidence that Pegasus is being used to target dozens of people in the democracy movement, confirmed by forensic examination of the phones of the victims. For the government to deny it knows anything about the hacking is clearly nonsense, and Chaiwut’s awkward U-turn gave the game away.

But it may indeed be true that it’s not the government or the police who are actually behind the spying.

Since he became king in 2016, Vajiralongkorn has created a personal army and security force, the Royal Guard 904, with more than 100,000 police and soldiers who undergo special training to indoctrinate them and report directly to him. The force includes several units tasked with monitoring the internet and investigating anybody perceived to be a threat to the monarchy, and operates separately from the regular military and police. It’s highly plausible that Vajiralongkorn’s personal security forces have been using Pegasus to hack the phones of supporters of democracy — they have unlimited funds and routinely operate outside the law, including by murdering at least 10 activists who had fled to other Southeast Asian countries.

Other murderous monarchies have also used Pegasus to target activists, including Saudi Arabia, which used the spyware to monitor allies of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi who was killed and dismembered in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018. The sheikhdoms of the United Arab Emirates are also prolific users, and Dubai ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum used Pegasus to spy on his estranged wife Princess Hala and her associates during their acrimonious divorce.

The Citizen Lab report didn’t mention the probability that Vajiralongkorn’s palace security force is using Pegasus, because it’s illegal to even just say so in Thailand. But they did mention three other Thai entities that are probable users of Pegasus, and which are confirmed to have also been users of complementary products which enable the interception of mobile phone calls and the real-time tracking of a phone’s location, sold by an NSO-affiliated firm called Circles.

One is the Narcotics Suppression Bureau, the division of the Royal Thai Police responsible for cracking drown on the illegal drugs trade, and which would have a legitimate reason for using NSO and Circle products in the fight against organised crime.

The other two are far more shadowy. The Internal Security Operations Command is a sprawling and secretive military organisation which claims to be dedicated to preserving national security, protecting the monarchy and promoting national unity, and which has tentacles that reach throughout the kingdom. It routinely uses political propaganda, information warfare, intimidation, coercion, and black ops. In the words of Puangthong Pawakapan, an expert on the organisation:

ISOC has branches in Bangkok and all 77 provinces. It has branches at all geographic levels: nationally, regionally, provincially all the way down to the villages. The operations are extensive. ISOC is intent on controlling the thoughts and political activities of civilians.

The third entity mentioned in the Citizen Lab report is the Military Intelligence Bureau, another wing of the army that also specialises in snooping on alleged threats to national security and disseminating propaganda and misinformation.

Prayut is director of ISOC and made organisational changes after the 2014 to expand its powers in the hope of crushing dissent against the junta. As a former army chief he is also well acquainted with military intelligence operations. It is simply not credible that he is unaware of the use of Pegasus to target the democracy movement.

What is clear is that some of the most malign entities in Thailand are using spyware to try to destroy the democracy movement.

Vote for me, I’m a notorious gangster

The Pheu Thai Party has high hopes of winning the next election, but it remains tainted by all the worst old elements of Thai politics and has never presented a coherent policy agenda for reform. It exists mainly to achieve leverage to allow Thaksin to strike a deal to return to Thailand, and as a patronage machine that attracts unprincipled politicians because it promises good prospects of electoral success. The likely nomination of Thaksin’s daughter Paetongtarn as the party’s prime ministerial candidate shows that Pheu Thai remains a political vehicle for the Shinawatra clan, and the recent announcement of the party’s first 21 election candidates in Bangkok provided more depressing evidence that Thailand’s main opposition party remains mired in nepotism and corruption and has little credible claim to any moral high ground.

Among the candidates is Wan Yoobamrung, second son of Chalerm Yoobamrung who is among the most unpleasant and corrupt of the previous generation of Thai politicians, standing out even in the grim cesspit of old-school Thai politics for his relentless lack of principle and impressive alacrity with embezzlement and graft. Chalerm began his career with the Royal Thai Police and after reaching the rank of captain, entered politics, initially with the Democrat Party. Like most politicians of his generation he switched his allegiance several times to whatever party seemed most expedient at the time. He fled to Scandinavia for a while after the 1991 military coup to evade accusations of corruption and unusual wealth. By the start of the 20th century he was an ally of Thaksin although he didn’t formally commit to affiliating to a Shinawatra party until he joined the People’s Power Party in 2007. The combative cigar-chomping political godfather preferred to maintain a semi-independent bloc of MPs for maximum leverage, much like Thammanat is doing today.

A couple of decades ago, Chalerm’s three sons Artharn, Wanchalerm and Duangchalerm were notorious in Thailand’s nightlife scene for their predilection for random violence. They didn’t really bother with their day jobs — Artharn and Wanchalearm joined the police but were fired after it was discovered they had forged documents claiming exemption from military service. Their father and his powerful allies ensured they got away with it. Their main activity in their privileged lives was going to nightclubs with a retinue of thugs and bodyguards, getting uproariously drunk, and savagely assaulting anyone they took a dislike to, for fun. As Time magazine reported in 2001:

Along the strip of hostess bars, cavernous discos and massage palaces of Bangkok’s Ratchadapisek Road, the Yubamrung brothers are the most infamous of the brawling brats of the Thai elite. During the past five years, Arthan, 30, Wanchalerm, 25, and Duangchalerm have been involved in at least a dozen bar fights and shootings.

This was a massive underestimate — the brothers were involved in brawls and beatings on an almost weekly basis.

In 2000 a prosecutor who was investigating the three Yubamrung boys was shot and wounded by a hitman who had been hired to kill him. Chalerm denied any responsibility, declaring:

A man like me does not need to hire anyone to kill someone else. I would do it myself.

The savagery of the brothers behaviour on their regular drunken trawls through Bangkok nightspots meant that sooner or later somebody was probably going to get killed, and sure enough, it eventually happened on October 29, 2001, at the Club Twenty coyote bar, where hostesses danced on tables and flirted to entertain wealthy men. Suwichai Rodwimud, a respected Crime Suppression Division police sergeant major who had been awarded the Crimebuster of the Year award, was celebrating at the club with colleagues after cracking a high-profile kidnapping case. Everybody was drinking and dancing, and late in the evening, Duangchalerm Yubamrung accused Suwichai of accidentally treading on his toe. A scuffle broke out and Duangchalerm told members of his entourage to restrain Suwichai, and said: “Do you know who my father is?” Then he pulled out a pistol and shot Suwichai in the head at pointblank range.

The brazen murder in a crowded nightclub was witnessed by dozens of people, several of whom identified Wanchalearm as one of the people who pinioned Suwichai’s arms before he was shot. The killing was egregiously shocking even in a country where people have long become wearily accustomed to the abusive antics and impunity of the rich kids of the elite. "Never before have Thais been this outraged over a murder case," said The Nation newspaper in a front-page editorial.

Facing arrest for murder, Duangchalerm fled to Cambodia via a border casino in Poipet that straddles the border. Meanwhile, Chalerm enlisted the help of all his most powerful allies including Thaksin, bribed and intimidated witnesses, and paid an impoverished stooge to take the rap instead by claiming he had pulled the trigger even though multiple witnesses saw Duangchalerm firing the fatal shot. He disposed of the suspected murder weapon — a pistol registered in his name — and claimed he had lost it. Chalerm travelled regularly to meet his fugitive son on the Cambodian border, despite claiming he had no idea of Duangchalerm’s whereabouts.

Once Chalerm was confident he’d paid enough bribes and done enough dirty tricks to ensure a favourable verdict, Duangchalerm emerged from hiding and surrendered to police. He was released on bail, and to nobody’s surprise but widespread national outrage he was acquitted of all charges in March 2004. The judges cited a lack of evidence and contradictory witness statements — even though dozens of people had seen Duangchalerm killing a respected police officer in a crowded nightclub, Chalerm had successfully induced enough witnesses to recant their initial statements to provide the pliant judges with an excuse to acquit him. Wanchalearm was cleared of the most serious charge of being an accessory to murder, although he was given a one-month suspended jail sentence and a 1,000 baht fine for assaulting Suwichai.

Duangchalerm was kicked out of the army when he went on the run but was accepted back in 2008. In 2012 he transferred to The Royal Thai Police, supposedly because of his expert marksmanship skills. Evidently, being a notorious cop killer who evaded justice was no barrier to being appointed to a senior position in the Bangkok Metropolitan Police Bureau as long as your dad is powerful enough. Chalerm insisted there was no nepotism involved and his murderous son had been appointed purely on merit:

This is not nepotism but he is a sharp shooter. Duang shoots very well and has 16 certificates. His shooting accuracy is 100 percent while mine is only 98 percent and there aren't many people in Thailand who have perfect shooting accuracy.

Brothel tycoon Chuvit Kamolvisit, who became an MP promising to expose corruption, said Duang’s transfer to the police was an insult to society, and if he really had 100 percent shooting accuracy he should have been sent to the 2012 Olympics in London instead.

Meanwhile, Wanchalearm changed his name to Wan in a comically inadequate attempt to dissociate himself from his scandal-strewn past and was appointed a ministerial adviser in Thaksin’s Thai Rak Thai party. He was embroiled in another controversy in 2017 when a photograph showing Wan and his family gorging on seafood at an upscale restaurant while their maid squatted on the floor went viral on social media. Wan publicly threatened the person who posted the picture, claiming that his maid was only on the floor because there was a shortage of chairs in the restaurant and she was suffering from back pain so preferred to sit on the ground.

In 2018 he was yet again involved in a brutal drunken assault in a nightclub. Wan, his 21-year-old son Archawin and several thugs in their entourage were in a Thonglor club when the spotted somebody they didn’t like — Panuwat Punnarattanakul, the son of a gold shop owner who had apparently quarrelled with Archawin on a previous occasion. Security camera footage showed Wan punching the victim in the face, knocking him to the ground, and then Archawin kicking him. One of Wan’s entourage fired a shot into the air to deter Panuwat’s friends from trying to intervene. Police had plenty of evidence, but as usual with the untouchable Yubamrung clan, Chalerm used his malign influence to ensure all charges were eventually dropped.

Wan and his two brothers are among the ghastliest offspring of Thailand’s political elite, unrepentant thugs and gangsters who evaded facing justice for a litany of crimes thanks to their powerful father. Wan has no discernible talents and the only reason he has been selected as a Pheu Thai election candidate is because of Chalerm’s patronage. Chalerm — who has held multiple cabinet posts over the decades and was a deputy prime minister in the administration of Yingluck Shinawatra — has even boasted that Wan will get a cabinet position too.

If he does get elected and secures a cabinet seat, he will of course be far from the only notorious crook in parliament — every major party has plenty of godfathers, gangsters, grifters and ghouls. But the candidacy of Wan Yubamrung is an insult to voters and shows once again that Pheu Thai has no intention of really reforming politics or rooting out powerful criminal clans from parliament.

The party’s popularity is based mostly on exploiting the Shinawatra brand and the perception that it is possibly slightly less awful and autocratic than the junta vehicle Palang Pracharat and the ossified Democrat Party which has consistently made a mockery of its name by siding with dictators. The fact that the main opposition party is little better than the ruling coalition is a depressing illustration of the sorry state of Thai politics.

Oppressive and unjust

Princess Sirivannavari, the most unpopular of all Vajiralongkorn’s children, has appeared on Thai television being interviewed by a fawning host who grovelled on the floor at her feet as she sat on a chair wearing a Snoopy T-shirt.

The excruciating scenes were reminiscent of the notorious interview of Princess Chulabhorn in April 2011 by Vuthithorn “Woody” Milintachinda who sat on the floor dressed in a tuxedo and bow tie, wept as the princess said the Red Shirt protest the year before had worsened the health of King Bhumibol and Queen Sirikit, and enthusiastically ate some of dog biscuits that Chulabhorn was feeding her pet Pomeranian called Luk Mee. (You can watch a clip of that interview here, and last year I published an article about Thailand’s royal dogs.)

King Chulalongkorn understood more than a century and a half ago that prostration was an archaic custom no longer compatible with international norms and values in a changing world. He abolished prostration in 1873, declaring: “In Siam, the practice of prostration reaffirms the existence of oppression which is unjust.” He noted that other countries where prostration had been practiced in the past, such as China, Japan, Vietnam and parts of India, had all abandoned the custom.

But in Thailand, prostration was revived during the reign of King Bhumibol, and continues to be demanded when Thais are in the presence of senior royals. Thailand is the only place in the world in the 21st century where prostrating on the ground is still expected.

Royalists claim that prostration is “Thai culture” but this is nonsense. Hundreds of years ago almost every country in the world expected ordinary people to debase themselves and grovel in the presence of their rulers, but this demeaning “culture” died away as countries became more advanced and ordinary people began to assert their rights to be treated equally. National culture is not static, it continually evolves, and there is no justification for preserving oppressive practices from the distant past.

Meanwhile, one of the many quirks of Thai royalism is that people are expected to prostrate on the ground when royals are nearby, but to stand up when the royal anthem video is shown in cinemas ahead of movies.

Far-right royal dinosaur Chulcherm Yugala has been berating Chadchart Sittipunt for allegedly failing to ensure that Bangkok cinemas always play the anthem and that everybody stands. Given the popularity of Chadchart and the plummeting reverence for the royals, plus the fact that most Thais don’t bother standing any more because they have no respect for Vajiralongkorn, his intervention just makes him look even more ridiculous.

Scared of a song

The regime is continuing its efforts to scrub all trace of a song by the excellent political musical collective Rap against Dictatorship from the internet. The song, called ปฏิรูป which means reform, was published online in November 2020 and geoblocked in Thailand 12 days later after the regime claimed it contains obscene language and threatened national security.

Last year the rapper Dechathorn Bamrungmuang aka Hockhacker petitioned the Criminal Court to overturn the ruling, but after a new hearing the court reaffirmed its original ruling on July 7. The video remains geoblocked in Thailand on most platforms but you can view it here:

The lyrics include criticisms of the regime for cracking down violently on the democracy movement, and for spending taxpayers’ money on a polygamist while ignoring their demand for reform, which is the main reason the government is so aghast about the song, even though there was no direct mention of Vajiralongkorn.

In response to the latest court ruling, Rap Against Dictatorship said:

Creating anything to reform, improve or change may be difficult in a totalitarian land at this time, but soon the time will come.

The group’s first single and brilliant accompanying video, ประเทศกูมี, has been viewed more than 106 million times on YouTube alone and is one of the world’s greatest political protest songs of the 21st century.

Beware of wearing black today

Today is Vajiralongkorn’s 70th birthday, and police around the country are on alert for anybody dressed in black, which they say is an insult to the monarch. As Prachatai reports, the national police chief, general Suwat Jangyodsuk, chaired a meeting on Tuesday which discussed reports that some activist groups have called on people to wear black for the king’s birthday to show their opposition to the monarch. There is of course no law in Thailand against wearing any particular colour on any particular day, but Suwat said it was “improper” to wear black on Vajiralongkorn’s birthday and told police to be on the lookout for any offenders.

That’s all for this edition, many thanks for reading and for following Secret Siam! 🙏

Welcome back. I've missed these updates. Glad to hear that you are doing better now. Do you think Thailand will ever be able to overcome the rampant corruption?

Superb as usual.....thank you Andrew for the insight into the scourge of humanity and depravity of totalitarian regimes.

Good health!